Utilizing Risk to Develop Food Safety Systems

Food safety systems can be examined in a systematic, risk-based way to aid food safety practitioners in their work

A risk-based approach is rapidly being incorporated into food safety systems. This can be attributed to the efforts of regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA's FSIS), and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Non-governmental organizations, such as the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI), have aided in these efforts by developing requirements for food businesses.

This article examines food safety systems from a systematic, risk-based approach to allow the food safety practitioner to develop and improve food safety.

HACCP: The Original Risk-Based Food Safety System

In 1959, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the U.S. Army Natick Research Laboratory partnered with the Pillsbury Company to develop a food safety system to prevent food safety hazards from being incorporated in the food for the U.S. space program. This system, known as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), was initially based on Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA). NASA was using FMEA to prevent engineering failures on the missiles and spacecraft. One major difference between FMEA and HACCP is that FMEA failures are assessed on three issues: severity, likelihood, and detectability of the failure; while HACCP hazards are assessed on severity and likelihood of occurrence of the hazard.

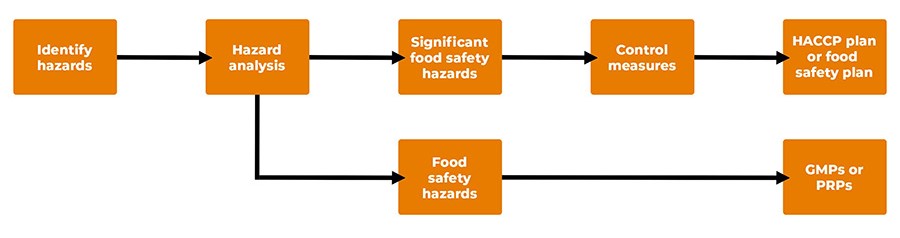

HACCP focuses on unintentional adulteration of the food produced at a site. This is accomplished by taking a strong preventive action approach. Throughout the years, incremental improvements have been made in the requirements for HACCP. This process allowed HACCP to slowly evolve, thereby making the system more robust and easier to use, rather than making the system more complex. Figure 1 summarizes the highlights of the HACCP system.

Figure 1. Highlights of the HACCP System

A food safety system has two parts. The first part is the foundation, which is based on Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) or Prerequisite Programs (PRPs). The PRPs create the environment to manufacture safe food. Bernard et al.1 made the following observations about PRPs:

- PRPs indirectly affect food safety issues

- PRPs are general and are applied throughout the food processing site

- In general, momentary failure to meet a PRP requirement does not lead to a food safety issue; however, breakdown of a PRP can lead to a food safety issue.

It is critical to properly develop, implement, and verify the PRPs used at the site. The objective of the verification process ensures that the PRPs are operating according to their planned activities. In addition, the verification activities also identify opportunities to improve the effectiveness of the PRPs.

HACCP is the second part of the food safety system. When PRPs are operating properly, the HACCP process can focus on controlling significant food safety hazards. Codex Alimentarius (2020) defines a significant food safety hazard in the following way: "A hazard identified by a hazard analysis, as reasonably likely to occur at an unacceptable level in the absence of control, and for which control is essential given the intended use of the food."2 Thus, HACCP focuses on reducing or eliminating significant food safety hazards or controlling them to an acceptable level.

After potential hazards are identified, the hazards are classified as significant food safety hazards or food safety hazards. This is accomplished by using a risk analysis process based on assessing the hazard for likelihood of occurrence and severity. After hazard analysis, a HACCP plan (food safety plan) is developed, implemented, and maintained.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Food Defense

The function of a food defense system is to protect the food manufacturer against a deliberate attack from a perpetrator. The attacker focuses on causing intentional adulteration of the food with the intent to harm customers or consumers. It is basically a terrorist attack on the site and brand(s) to gain publicity in the media. To counter an attack, a food processor implements a food defense system using Threat Analysis and Critical Control Points, or TACCP.

Two basic methods to develop a food defense plan exist. The first method is based on the PAS 96:2017 Guide to Protecting and Defending Food and Drink from Deliberate Attack.3 Essentially, PAS 96 utilizes TACCP principles and builds the food defense systems from the ground up. The following provides a summary of the requirements of the standard:3

- Understand the type of perpetrator or attacker: the extortionist, the opportunist, the intentional individual, the disgruntled individual, the cybercriminal, and the professional criminal

- Identify the types of threats or vulnerabilities including economically motivated adulteration, malicious contamination, extortion, espionage, counterfeiting, and cybercrime

- Conduct a risk assessment of the threats

- Develop control points for each threat

- Develop a response to incidents.

A second method is to construct the food defense plan using the FDA Food Defense Plan Builder (version 2.0.)4 Note that GFSI-recognized certification schemes can use the FDA Food Defense Plan Builder process as a means to meet GFSI requirements for food defense.5 The Food Defense Plan Builder also meets the FDA regulations cited in 21 CFR 121. Thus, the FDA approach focuses on an approach to prevent intentional adulterations. FDA provides a computer application that maintains the food defense plan in a digital form. FDA emphasizes that this application does not link to FDA computers.

The Food Defense Plan Builder contains the following information:

- Information on the food site

- Information on the food defense team

- Product and process description

- Vulnerability (threat) assessment

- Mitigation procedures

- Monitoring, corrective action, and verification procedures

- Supporting documentation

- Authorizing signatures.

The food defense system is based on a two-pronged approach, similar to the HACCP approach. The first prong is to secure the site. The objective is to keep unwanted individuals off the site. Therefore, sites can focus the human resource issues on employees and visitors such as contractors, consultants, etc., that have been invited on the site. Once the site is secure, the TACCP part of the system focuses on the vulnerabilities that are specific for the manufacturing processes and products.

FDA Guidance for Industry: Food Security Preventive Measures Guidance for Food Producers, Processors, and Transporters6 provides guidance to secure the site. It addresses the following topics:

- Management must be committed to developing, implementing, and maintaining the food defense system

- Factors relating to the human element: employee screening, work assignments, identification, restricted access, personal items, training in security procedures, unusual behavior, staff health, and procedures to control visitors when onsite

- Factors relating to the physical facility: physical security, laboratory security, storage, and use of poisonous and dangerous chemicals

- Factors relating to operations: incoming and contract operations, storage, secure water and utilities, finished products, mail packages, and access to computer systems.

The guidance document contains a checklist to aid in the site assessment.

FSIS also published a food defense mitigation tool7 to provide assistance to FSIS-inspected establishments in conducting vulnerability assessments and selecting applicable mitigation strategies.

Food Fraud

Food fraud is the intentional and economically motivated adulteration of foods. Economically Motivated Adulteration (EMA) is defined as the fraudulent addition of non-authentic substances or the removal or replacement of authentic substances, without the purchaser's knowledge, for economic gain of the seller.8 A food fraud system uses a process similar to HACCP, known as Vulnerability Analysis Critical Control Point (VACCP). The primary focus in the prevention of food fraud is an effective supplier procurement program and strong interactions with suppliers.

Over the years, a number of food products have been implicated in food fraud issues:

- Olive oil

- Honey and maple syrup

- Herbs and spices

- Fish

- Fruit juices

- Coffee and tea

- Wine

- Organic products.

The fraud can be achieved by:

- Substituting

- Adulterating or diluting

- Mislabeling

- Making false claims or misleading statements on the contents of the product.

In 2016, the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) published a major document that provides guidance for developing a food fraud system.8 This document is an appendix to the Food Chemical Codex. The USP points out that food fraud does not readily fit in the risk-based system that is used in either HACCP or TACCP, since the perpetrator's objective is to avoid detection. Specific incidents tend to be more difficult to anticipate and detect. As a result, the USP document uses the term "vulnerability" rather than "risk" or "likelihood of occurrence." As part of the food fraud system, the site can assess the types of vulnerabilities, and then use the outcomes of the identified vulnerabilities to develop mitigation strategies.

A number of contributing factors can affect ingredient vulnerability in a positive or negative manner:8

- Supply chain: Helps determine the degree of control that suppliers have in preventing fraud, among other actions.

- Audit strategy: Assesses the strength and maturity of the audit process, including whether auditors are auditing for components of a food fraud system.

- Supplier relationships: The primary assumption made is that the closer the relationship is between the supplier and the customer, the more knowledge and confidence each party will have in each another. For example, what were the interactions between the supplier and the customer when there were past issues? Were those issues successfully resolved, and how? Does the supplier notify the customer when a change is made to an ingredient or to a manufacturing process for the ingredient?

- History of the supplier's regulatory, quality, and food safety conformance: Assesses the ability of the supplier to control food safety and quality factors and to quickly and effectively respond to corrective action requests. In addition, it assesses the supplier's compliance with regulations.

- Analytical methods and specifications: Assesses the ability of the supplier's analytical methods to determine compliance to both food safety and quality performance indicators.

- Testing frequency: Are certificates of analysis (COA) included with each lot, or does the supplier provide a continuing letter of guarantee (COG)? What are the testing and statistical protocols for generating a test result? Were the tests conducted in a laboratory that met ISO 17025 requirements or an equivalent standard? Was the test conducted using a validated test method?

- Geopolitical considerations: Evaluates the adulteration history, economics, and complexity. Demographics are conducted to determine if a specific region of the world is more susceptible to food fraud. Are ingredients sourced from areas of the world where geopolitical considerations must be taken into account?

- Fraud history: Determines if a specific ingredient or component has been the target of food fraud. This includes determining the legitimacy of any food fraud reports. Have suppliers implemented effective food fraud plans?

- Economic anomalies: Some economic factors can cause a sharp change in the price of an ingredient that makes the ingredient susceptible to EMA.

Once the factors have been identified, the site can develop a strategy to reduce and manage the vulnerability of an ingredient or component to an acceptable level. Commercially available databases can be purchased or rented to assist in the development of a food fraud plan. The food fraud plan should be reviewed periodically to ensure that it is both effective and efficient.

Food Safety Culture

Food safety culture is a hot topic. Recently, GFSI added requirements for auditing food safety culture.5 In addition, the concept of food safety culture has been added to the latest revision of the Codex Principles of Food Hygiene standard.2

GFSI defines food safety culture in the following way: "Shared values, beliefs, and norms that affect mindset and behavior toward food safety in, across, and throughout an organization.9 GFSI states that the elements of a food safety culture consist of the following:

- Communication

- Training

- Employee feedback

- Performance measures of food safety activities.

Audit requirements for a food safety management scheme must focus on auditable requirements. However, if a company wants to have a strong food safety culture, then the company must go beyond the auditable requirements. A food safety culture must also focus on the mindset and behavior of all employees from senior leaders (top managers) to line employees. The actual behavior of the top management or senior leaders is critical for the success of the food safety, food defense, and food fraud programs. Leaders at all levels in the organization need to not only "talk the talk" but also "walk the walk." In developing a food safety culture, it is important to remember an old saying: Actions speak louder than words.

References

- Bernard, D. T., N. G. Parkinson, and Y. Chen. "Prerequisites to HACCP." In V. N. Scott and K. E. Stevenson. HACCP: A Systematic Approach to Food Safety. 4th Ed. Washington, D.C.: Food Processors Association, 2006

- Codex Alimentarius. CXC 1-1969: General Principles of Food Hygiene. Geneva, Switzerland: 2020.

- British Standards Institution (BSI). PAS 96:2017: Guide to Protecting and Defending Food and Drink from Deliberate Attack. London, UK: 2017.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Defense Plan Builder. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-defense-tools/food-defense-plan-builder.

- Food Safety System Certification (FSSC). Food Safety Certification 22000 Guidance Document: Food Defense. 2019. https://www.fssc22000.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Guidance_Food-Defense_Version-5_19.0528.pdf.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Food Security Preventive Measures Guidance for Food Producers, Processors, and Transporters. 2007. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-food-security-preventive-measures-guidance-food-producers-processors-and.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service. FSIS Food Defense Risk Mitigation Tool. 2022. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/food-defense-and-emergency-response/food-defense/risk-mitigation-tool.

- U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention. Food Fraud Mitigation Guidance, Appendix XVII: General Tests and Assays. 2016. https://www.usp.org/search?search_api_fulltext=food fraud mitigation.

- Food Safety System Certification (FSSC). Food Safety Certification 22000 Guidance Document: Food Safety Culture. 2020. https://www.fssc22000.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FSSC-22000-Guidance-Document-Food-Safety-Culture-_Version-5.1.pdf.

John G. Surak, Ph.D., is Principal of John Surak and Associates. He provides consulting on food safety and quality management systems, auditing management systems, validating manufacturing processes, designing and implementing process control systems, and implementing Six Sigma and business analytics. Dr. Surak is also a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Food Safety Magazine. He can be reached at jgsurak@yahoo.com.