Rings of Defense: Justifying and Negotiating Food Safety Actions to Regulators

In the stress of an inspection where a noncompliance is found, it is important to consider all avenues for corrective actions

In defending food safety procedures and practices to an inspector who is challenging them, it can be easy (and even tempting) to give in to the inspector's wishes. It can help quell arguments or awkward moments, and perhaps allow an embarrassing moment to get lost in the dust by moving the inspection forward.

Yet, this is also the way to commit yourself to "giving away the store"—that is, agreeing to changes in policies, procedures, practices, and/or people with which you do not really agree, or which might cost more time and money than is proportional to the issue at hand. Such changes also may not really solve the underlying issue or root cause, regardless of whether or not the inspector has identified these accurately.

This article shares a successful strategy to handle the pressure of an inspection or audit that has found an immediate noncompliance. Rather than agree to do everything possible to ensure that the specific issue does not happen again, there is a step-wise approach that offers up the minimum needed. The strategy involves sharing the easiest line of defense (i.e., action to be taken) first, and then falling back on increasingly stronger rings of defense if and as needed. Doing so sequentially and strategically has the advantage of keeping you from having to "play all of your cards" at once, of minimizing unneeded changes to procedures and practices, and of potentially avoiding a major noncompliance (or recall) by ensuring that the issue is addressed.

The disadvantages are that you might not get a chance to move to a stronger ring of defense, you might risk alienating the inspector, and you might lose credibility with the regulatory authorities and receive a substantial noncompliance violation anyway. Hence, experienced judgement is needed. This strategy is not for the faint of heart; but it is for everyone who wants to ensure that an inspection is handled fairly on behalf of the company.

The Rings of Defense

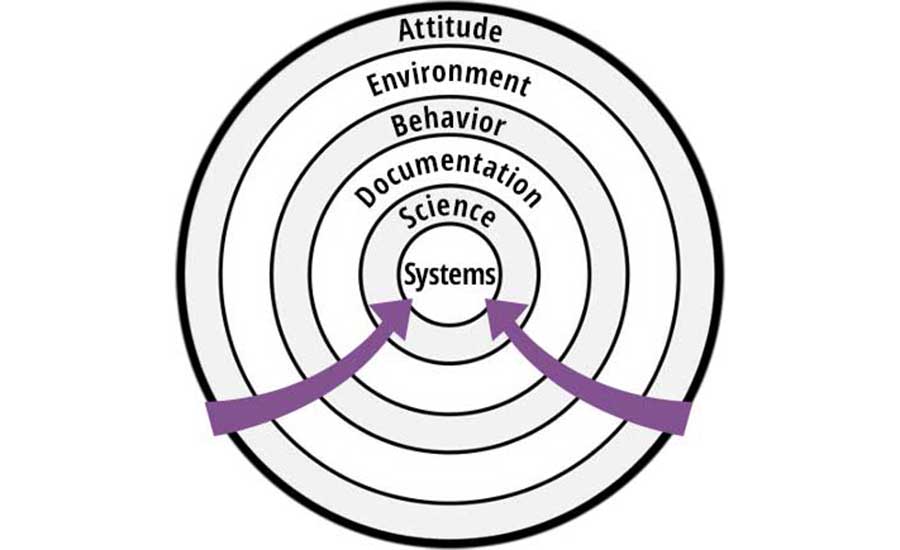

The strategy of the "rings of defense" can be visualized by Figure 1. The outermost ring is the easiest defense to offer to an inspector and is meant to protect the innermost "bullseye," which is a complete change to underlying systems. The latter is typically the longest to execute, impacts the most people, and is the costliest.

Moving inward through successive rings commits the organization to increasingly difficult solutions, albeit perhaps warranted to eliminate the root cause. It is important to understand that this strategy is not advocating not solving the problem—rather, it is providing a framework to allow the organization to think through simpler and less costly solutions to the problem than might otherwise be hastily offered. The obvious solution to the problem may already reside within one of the inner rings; if so, this should be offered to the inspector immediately.

The Strategy of Each Ring

Let us define each ring and what benefits each one provides. Table 1 at the end of this section also provides a handy summary.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Ring 1: Attitude. If the culture of the company includes a track record of doing the right things right, and this is obvious and accepted by the inspector, then sometimes the easiest thing to explain is that the company really meant to do things right; it just hiccupped in the instance under scrutiny by the inspector. Even if this is not sufficient, it can at least be used as a springboard for a discussion on the company's aspirations and desires. This stage-setting can be very helpful in setting the context for subsequent conversations.

Ring 2: Environment. Often heard by inspectors is the phrase, "this has never happened before," so this rationale generally has low credibility. However, if the situation truly is one that is able to be substantiated as unique (a "one-off"), then it is worth providing this rationale. Proof and data are needed. Just because the inspector "has heard this before" is no reason not to give this approach serious consideration when it really is true.

Ring 3: Behavior. Now we are getting into the real nuts and bolts of a noncompliance, since something untoward did indeed happen. The error must be admitted—not smoke-screened—and then addressed. This strategic ring suggests that it can be proposed that the right thing was indeed practiced; the documentation was just not filled out correctly. If this is true, then all efforts should be made to show that the right behaviors are continually practiced. Evidence could include, for example, records from the past three months of production that show 100 percent compliance to the issue in question.

Ring 4: Science. In this case, perhaps the wrong behavior did indeed occur, or it was not exactly what the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) called for. Although a variance with an SOP may be in play, it could be that the exhibited behavior is still consistent with what the appropriate science might support. This does not mean that the behavior is justified, especially in the eyes of an inspector, but having scientific support can provide evidence that the overall risk was much lower than might have been initially assumed by the inspector.

Ring 5: Documentation. The documentation implies that the right thing was done, although it really was not (whether or not the inspector knows this). Rather, an error truly was made in practice (e.g., not following an SOP). This is a defensive ring in which commitments to real change need to be made. Hence, utilizing the strategy of this ring is significant. Real resources need to be brought into play, and real commitments to change must be made.

Ring 6: Systems. There are times when the inspector has noted a real failure in operations that cannot be hidden, and must be dealt with head-on. Not doing so could result in a recall, or worse, could cause harm to a consumer. This ring requires significant, unwavering commitment to change, and is definitely "giving away the store" because it requires as much. Not doing so risks not having a "store" anymore.

Example: Sanitizer Concentration

Let us say that the inspector has noticed that an entry on a data log shows that the concentration of sanitizer used on a certain date was below the low end of the range specified in the SOP. For example, for a set of quaternary ammonium compounds, the label specifies a dilution of 5.0–6.0 ounces (oz) per gallon of water. The sanitizing team operator has recorded a dilution level of 4.0 oz/gal, clearly below the 5.0 oz/gal minimum per the SOP. For the purposes of this example, we are not discussing actual ppm per the sanitizer label, nor are we discussing rinse versus no-rinse levels.

A "Ring One" (attitude) response might be that the dilution level was likely correct because that has been the requirement of the company ever since that particular sanitizer was brought into use.

A "Ring Two" (environment) response, assuming no success of the first ring, might be that the dilution levels have been correct 100 percent of the time for the past three months. Data need to be presented to prove this.

A "Ring Three" (behavior) response might be that the operator involved was new, and was not trained well. Re-training, with verification of this training, may be offered as an action step to the inspector. However, the fact that sanitizer concentration was below a specified level must be addressed. This could be an action related to product made on that line in the day in question, and/or could relate to using the strategy in the next ring.

A "Ring Four" (science) response might be to review the relevant label and scientific literature on the quats being used. Very likely, these data show that lower concentrations are still effective. If that is the case, then it can be argued that the error was not the efficacy of the product, but was instead in not following the SOP. If so, then there might be minimal, if any, consequence relative to product being made on the line subsequent to the sanitization.

A "Ring Five" (documentation) response might be owning up to the fact that the wrong practice was indeed executed, even if all events in the past have been correct. Rather than try to explain this as a "one-off," the documentation clearly shows that the wrong action was taken. In this event, re-training of all operators, verification of this training, and an ongoing double-check of paperwork (e.g., supervisor sign-off) might be warranted. Depending on the scientific support (above) for how efficacious the actual quat concentration was, some action might be needed relative to finished product.

A "Ring Six" (systems) response should be a candid admission of a systemic breakdown. This is suggested as a strategy only when none of the above approaches are successful, and/or when there truly was a systemic breakdown. This is often hard to recognize and even harder to admit, but in the right circumstances, this is absolutely the right approach to take. It might entail a top-to-bottom review of how sanitizers are brought into the company, whether the labels and SOPs are accurate and current (including a review of the scientific literature), disciplinary action for the operator(s) and/or supervisor(s) and/or manager(s), re-training of all operators with verification being conducted for a substantial length of time, and sign-offs of relevant paperwork by a person of high authority. In addition, complete traceability of product made on the relevant lines could be in order, with possible market withdrawal or recall.

Example: Meat Cooling Temperature

Let us say that the inspector has noticed that an entry on a data log shows that a meat cooking operator recorded a temperature during the cooling of meat at a time that was later than the maximum allowable time per USDA compliance guidelines. For example, the guideline specifies that meat should not remain between 130 °F and 80 °F for more than 1.5 hours. The operator recorded a temperature of 70 °F at 2 hours, in this example.

A "Ring One" (attitude) response might be that the temperature at 1.5 hours was likely 80 °F or below because that makes a lot of intuitive sense.

A "Ring Two" (environment) response, assuming no success of the first response, might be that meat temperatures at 1.5 hours have always been 80 °F or below for every batch of meat produced for the past three months. Data need to be presented to prove this.

A "Ring Three" (behavior) response might be that the operator involved became busy with an urgent production issue on another line and could not get back to the cooling station in time. Redistributing operator responsibilities may be offered as an action step to the inspector. However, the fact that the meat temperature might have been a bit too high for too long must be addressed. This could be an action related to the specific batch of meat made, and/or could relate to using the strategy in the next ring.

A "Ring Four" (science) response might be to use a graphical approach to show cooling curves for the meat in question. In the right circumstances, this could involve the use of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Integrated Pathogen Modeling Program–Dynamic Prediction to predict the time frame of growth of pathogens. The objective is to demonstrate mathematically and statistically that the meat must have been 80 °F or below at 1.5 hours, and/or that pathogens could not have grown. Note that this approach is useful only when the temperature and time are reasonably close to the USDA guidelines.

A "Ring Five" (documentation) response might be owning up to the fact that the wrong practice was indeed executed. Re-training of all operators, verification of this training, and an ongoing double-check of paperwork (e.g., supervisor sign-off) might be warranted. Depending on the scientific support (above) for how well the meat was cooled, some action might be needed relative to finished product.

A "Ring Six" (systems) response should be a candid admission of a systemic breakdown when management is aware that this is what actually happened. This could involve a data-based review of all cooling records for the past three months, line by line, product by product. It might also involve disciplinary action and verified re-training, as well as the involvement of senior management in subsequent product release documentation. A complete traceability must be conducted for all meat products that might not have been cooled properly.

Summary

The strategy presented in this article is meant as a tool to help a food safety team and its management successfully manage an inspection or audit that has identified a noncompliance. Each step in the "rings of defense" must be used consciously and with proper consideration, as it may be obvious what caused the noncompliance, and its resolution may be straightforward, simple, and not costly.

The strategy is also meant as a step-wise approach so that, in the stress of an inspection, all avenues for corrective actions are considered. This prevents the error of missing an action that is easy to take, and it prevents the unconditional offer of a complete systems overhaul.

Successful use of the "rings of defense" strategy comes from practice to develop good judgement skills, and from being able to adjust the approach based on the skills, knowledge, and temperament of the inspector.

Doing this right means that missing the bullseye is a win.

Bob Lijana, M.Sc., has held director- and VP-level positions in food safety, quality, and operations for over 35 years at companies producing ready-to-eat foods, prepared meals, and pasteurized juices. He has a B.Sc. and an M.Sc. in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California–Berkeley, respectively.