The Reportable Food Registry: A Valuable New Tool for Preventing Foodborne Illness

When Congress created the Reportable Food Registry (RFR) in Section 1005 of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Amendments Act of 2007, FDA was given the opportunity to develop a useful addition to its armamentarium of tools and techniques to prevent foodborne illness. In the law, which became Section 417 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), Congress directed that FDA establish an electronic portal to which industry must, and public health officials may, report when there is a reasonable probability that an article of human food or animal food/feed (including pet food) will cause serious adverse health consequences or death to humans or animals.

In its first year of operation, the RFR has had an impact on the prevention of foodborne illness. As Michael R. Taylor, FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Foods, has pointed out:

“The RFR represents an important tool for targeting our inspection resources, bringing high-risk commodities into focus, and driving positive change in industry practices—all of which will better protect the public health.”

What Is It?

Depending on the circumstances of a particular case, the RFR can be an early warning of an adulterated food or feed, a map of the progress of an adulterated food or feed through the supply chain, or both. In all circumstances, the RFR makes significant sectors of the food and feed industries partners with FDA in tracking down food and feed that has the potential to cause serious illness. The RFR obliges manufacturers, processors, packers, and holders of food or feed to notify FDA via an electronic portal whenever they determine that they have a reportable food, that is, “an article of food for which there is a reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, such article of food will cause serious adverse health consequences or death to humans or animals.” In addition, government public health officials may voluntarily use the portal to report information that may come to them about reportable foods.

Dietary supplements and infant formula are exempted from the RFR requirements because reporting of adverse events associated with them are covered under other sections of the FD&C Act.

Because submissions to the RFR include supply chain information, that is, the immediate previous source(s) and/or immediate subsequent recipient(s) of a reportable food, they help FDA identify both the site where the adulteration may have occurred as well as the locations of food products moving through commerce to the retail level. As a result, the RFR has already achieved several notable successes in removing adulterated foods from the supply chain before any illness associated with them occurred, of which more is described later in this

article.

How Does the RFR Work? Mandatory Reporters

The persons who register facilities with FDA that manufacture, process, pack, or hold food or feed for consumption in the U.S. are responsible parties in the language of the RFR and for them, the requirements of the RFR are mandatory. The most important requirement is that within 24 hours of a responsible party determining that a facility has an instance of reportable food, they must submit a report to FDA through the Department of Health and Human Services’ Safety Reporting Portal (SRP) at www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov.

As used in relation to the RFR, the term “responsible party” does not refer to the responsibility for a food being adulterated, but to the responsibility to report if a facility determines or is notified that it has or has had a reportable food in its possession. There should be no confusion about responsible parties—if you are registered under Section 415 of the FD&C Act and you determine that you have or have had an article of food that meets the definition of a reportable food, you must report it to the portal. There is one scenario, however, when a responsible party does not have to report. This is true only when all three of the following criteria are met:

1. The adulteration originated with the responsible party AND

2. The responsible party detected the adulteration prior to any transfer to another person of such article of food AND

3. The responsible party

a. corrected such adulteration or

b. destroyed or caused the destruction of such article of food

A transfer to another person occurs when the responsible party releases the food to another person. “Person” is defined in Section 201(e) of the FD&C Act as including individuals, partnerships, corporations, and associations. FDA does not consider an intra-company transfer in a vertically integrated company to be a “transfer to another person,” where the company maintains continuous possession and control of the article of food. For example, if Company A owns a processing plant, warehouse facility, and distribution facility, the intra-company transfer from the processing plant to the warehouse facility and/or the warehouse facility to the distribution facility would not be considered a transfer to another person.

Voluntary Reporters

The law that created the RFR gives government public health officials the option of providing voluntary submissions to the portal if they have information about reportable foods, but they may not file a report on any firm’s behalf. However, if officials identify a reportable food as part of their inspection or regulatory activities, they can inform the firm that submission of a reportable food report may be required.

Submitting a Report

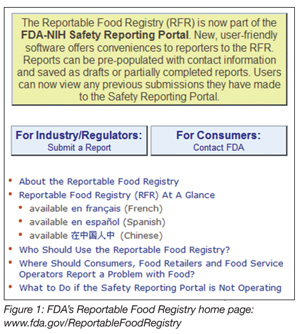

Mandatory or voluntary reporters can go directly to the SRP home page at www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov, or they can go to www.fda.gov/ReportableFoodRegistry (Figure 1) where they will find a wealth of RFR information and guidance, as well as a button that will also take them to the home page of the SRP. There they will have the option of creating an account or submitting a report as a guest. Creating an account provides submitters with many advantages. It allows reporters to save both partial and completed reports; any time they return to the portal, their new or amended reports will be pre-populated with their contact information; and they can view any previous submissions they have made via the SRP. Persons reporting as guests receive none of these benefits.

After the whether-to-create-an-account-or-not decision has been made, the portal will lead submitters through a series of screens that captures the information that FDA needs to get reportable foods out of the food supply as quickly and efficiently as possible.

The information required in submitting a report by a responsible party is what FDA needs to know in order to

investigate:

• FDA registration number of the responsible party in the case of a mandatory report

• Date on which the article of food was determined to be a reportable food

• A description of the article of food, including the quantity or amount

• Extent and nature of the adulteration

• Results of any investigation of the cause of the adulteration, if it may have originated with the responsible party, when known

• Disposition of the article of food, when known

• Product information typically found on packaging, including product codes, use-by dates, and the names of manufacturers, packers, or distributors sufficient to identify the article of food

When the report is submitted, the system issues an Individual Case Safety Report (ICSR) number, an identifier unique to each report.

If some of the required information is not available within the 24-hour reporting window, the RFR allows amended reports to be filed as the required data become available.

While the information fields on the Reportable Food portal differ somewhat between mandatory and voluntary submitters, they are both intuitive and not difficult to follow. The fields are a “rational questionnaire,” meaning that in many instances, the answer to a question dictates what the next question will be.

Technical Assistance

Because the food and feed industries are large, various, and complex, FDA has posted guidance to assist submitters with concerns about how their individual situations relate to the Registry. The Draft Guidance for Industry: Questions and Answers Regarding the RFR as Established by the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 (Edition 2), can be accessed via www.fda.gov/ReportableFoodRegistry.

In addition, there are two Help Desks, the RFR Center at RFRSupport@fda.hhs.gov for questions about policies, procedures, and interpretations and the SRP Service Desk at support.srp@jbsinternational.com for technical and computer-related questions about both RFR reports and the SRP.

Review by FDA

When a reportable food report is submitted to the SRP, it is sent to FDA’s Risk Control Review (RCR) team for review. The RCR team includes the following FDA organizations: the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, the Center for Veterinary Medicine, the Office of Emergency Operations, and the Office of Regulatory Affairs, which includes FDA’s 19 District Offices at locations throughout the nation. In addition, the District Office for the area from which the report originated receives a copy and participates in the review. Each report is reviewed to assess whether the subject of the report meets the definition of a reportable food and to identify appropriate follow-up actions. If the RCR team concludes that the submission is a reportable food, the submission is entered into the RFR, and appropriate follow-up measures are specified. All such reports are then referred to the appropriate FDA District Office for follow-up. Follow-up is undertaken in collaboration with the appropriate regulatory commissioned officials in the state or states involved who are automatically notified of any reportable food reports from facilities in their jurisdictions.

When necessary, an FDA District Office investigator will contact the firm or individual submitting the report to obtain additional information. The investigator may follow up with a visit to the firm. If needed, the District Office will advise the responsible party to notify the immediate previous supplier(s) of materials and/or the immediate subsequent recipient(s) of a reportable food and provide them the initial ICSR.

If a submission indicates that a food or feed may have been intentionally adulterated, FDA immediately sends a copy of the report to the Department of Homeland Security. If the food in a submission is under the exclusive jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), a copy of the report is sent to USDA. If a submission involves a food or feed or an ingredient imported into the U.S., FDA contacts the competent authority in the exporting country.

The RFR’s First Year

FDA has published its First Annual RFR Report (Sept. 8, 2009 – Sept. 7, 2010). It can be accessed at www.fda.gov/ReportableFoodRegistry. Here are some of the highlights from that report.

Submissions

Out of 2,600 submissions, 2,240 were deemed reportable foods and entered into the RFR. Of the remainder, some concerned drugs or medical devices; some were for foods under the exclusive jurisdiction of USDA, which are exempt from the RFR; a number were questions from consumers; and a few were deemed not reportable by the RCR team. When an incident is found not to meet the definition of a reportable food, the FDA District Office notifies the submitter.

Of the 2,240 RFR entries, 229 were primary reports—the initial report concerning a reportable food from either industry or public health officials; 1,872 were subsequent reports submitted by either a supplier (upstream) or a recipient (downstream) of a food or feed as a result of a primary report; and 139 were amendments to previously submitted primary or subsequent reports. Human food was the subject of 201 primary reports and 28 concerned animal feed/pet food.

Commodities and Food Safety Hazards

The 229 primary reports involved 25 commodities. Among the commodity leaders in the overall number of primary reports were the following: animal feed/pet food; dairy; seafood; spices and seasonings; bakery goods; nuts, nut products, and seed products; and produce (raw agricultural commodities, RAC).

The leading food safety hazards among the 229 primary reports were Salmonella and undeclared allergens/intolerances, that is, failure to declare the presence of any of the eight major human food allergens (i.e., milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans) or proteins derived from them. This category also includes undeclared sulfites. Sulfite intolerances mimic the symptoms caused by a food allergy.

Salmonella was responsible for 86 primary RFR entries (37.6%) involving 18 commodity categories. The bulk of the Salmonella entries concerned spices and seasonings; produce (RAC); animal feed/pet food; and nuts and nut

products.

In addition, undeclared allergens/intolerances were the cause of 80 primary RFR entries (34.9%), also involving 18 commodity categories. Bakery goods; fruit and vegetable products; prepared foods; dairy; and chocolate/confections/candy were the leading commodities reported because of this problem.

In view of the fact that the Congressional intent of the RFR is to help FDA better protect public health by tracking patterns of food and feed adulteration and targeting inspection resources, the RFR data suggests that Salmonella and undeclared allergens/intolerances require targeting by both industry and FDA. To some extent, this has already begun. A national trade association has recently developed guidance to reduce the risk of pathogen contamination in spices. Similarly, a national baking trade association is reviewing and enhancing its guidance on preventing unintended allergens from being introduced into bakery products.

For its part, FDA intends to include an annex on nuts with industry guidance the agency is developing on the control of Salmonella in low-moisture foods because of the high incidence of primary RFR entries involving Salmonella in nuts and nut products. In addition, FDA is preparing a publication explaining FDA’s sulfite regulation and labeling requirements because of RFR entries concerning imported dried fruits and vegetables with undisclosed sulfites. The publication will be targeted to FDA’s regulatory counterparts and the food industries in countries exporting dried fruits and vegetables to the U.S.

Regulatory Initiatives

FDA studies RFR entries for signals of larger systemic food safety issues that may be affecting a commodity, a region, or an entire industry. Early detection enables FDA to thoroughly investigate existing or emerging issues and then apply focused regulatory strategies to mitigate or eliminate the concern before it becomes a major problem or a foodborne illness outbreak. Such regulatory initiatives assist FDA in focusing limited resources on eliminating the sources of food safety problems. Several regulatory initiatives resulted from the RFR’s first year of operation, including the following:

Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein (HVP)

A food manufacturing facility received a shipment of a flavor enhancer, HVP, which tests showed to be positive for Salmonella Tennessee. The facility submitted a reportable food report to FDA, identifying the problem and its supplier. FDA conducted a risk control review analysis and consulted with both the primary report submitter and the supplier. The supplier voluntarily recalled the product and submitted a reportable food report. FDA requested that the supplier notify the immediate subsequent recipients of the reported HVP, which helped FDA identify the many other recipients of the ingredient. FDA worked with the recipients to address their specific situations. This resulted in 177 products containing the recalled HVP being removed from commerce. No illnesses associated with the recalled ingredient have been reported.

Prepared Side Dishes

A food manufacturing facility submitted a reportable food report notifying FDA that two nationally distributed prepared side dishes had been inadvertently produced with an ingredient containing sulfites, which were not mentioned on the labels. Individuals with a severe sensitivity to sulfites run the risk of a serious, potentially life-threatening reaction if they consume them. Within 3 days, the reportable food electronic portal received 108 subsequent reports from facilities that had received the implicated products and the manufacturer initiated a voluntary recall. No adverse events associated with these products have been reported since the primary report was submitted.

The manufacturer of the prepared side dishes implemented additional preventive controls in consultation with FDA and enhanced their employee training.

Glass in Animal Feed

A dairy farmer received a trailer load of pelleted feed that contained glass of various colors dispersed among the pellets. The dairy farmer reported the incident to the feed company, and the feed company submitted a reportable food report. An investigation by the feed company determined that the glass was a result of an incomplete cleaning of the delivery trailer. The feed company surmised that the glass contamination was due to glass that fell between cracks in the trailer floor boards and worked its way up into the load of feed. The carrier that the feed company hired reported shipping a prior load of recycled glass in the same trailer. However, between the shipping of the recycled glass and the feed to the dairy farmer, a load of a raw feed ingredient was delivered to a feed processing facility.

An inspection of the feed processing facility by the state regulatory agency determined that the facility had adequate preventive measures in place to remove the glass. No glass was found in the processing facility’s finished product. The feed delivered to the dairy farmer was destroyed. No animals were injured. As a result, the feed company re-evaluated the method by which they transport their products.

FDA Inspectional Initiatives

RFR entries triggered follow-up investigations by FDA that resulted in:

• Two Import Alerts: Import Alerts are guidance documents for FDA field staff concerning significant new, re-occurring, or unusual problems affecting import coverage. They include background data and guidance for appropriate enforcement action (generally, detention without physical examination) regarding each product and/or problem.

• Five Import Bulletins: An Import Bulletin typically provides information for FDA field staff on a suspected problem affecting FDA-regulated imported products. Import Bulletins generally call for increased surveillance (field examination and/or sample collection) of suspected problem products. The results of that increased surveillance may lead to subjecting a firm and/or product to an Import Alert.

• Four Field Assignments: This is FDA’s term for specific instructions and compliance information to FDA District Offices to address a particular problem relating to FDA-regulated domestic or imported products.

Next Steps: International Outreach

As of February 2011, there were approximately 167,000 domestic food facilities and 254,000 foreign food facilities registered with FDA. During the first year of the RFR, however, the number of primary RFR entries involving foods and ingredients from international sources was relatively small. FDA believes this may be, at least in part, the result of a lack of awareness by many foreign food facilities of the RFR and its requirements. Consequently, FDA is pursuing outreach efforts that target the international arena.

An RFR training video is in development that will explain the RFR and its requirements. FDA intends to post the video on FDA.gov and provide closed-captioning in Arabic, Chinese, French, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, and

Spanish.

The Reportable Food Registry at a Glance, a summary that has been widely distributed to U.S. food facilities, is now available in Chinese, French, and Spanish for distribution by FDA foreign posts to food facilities and competent authorities around the world.

Some 70 delegations of foreign government and industry representatives from over 50 countries, both developed and developing, visit FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition annually. The focus of presentations made to them are in part determined by requests from the delegations but, beginning in 2011, FDA is giving an RFR presentation to each visiting delegation.

RFR Enhancements

An important focus for FDA in the coming months will be execution of the new tasks Congress has added to the RFR process. The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), which President Obama signed into law on January 4, 2011, included Section 211, Improving the Reportable Food Registry. The changes, which are to take effect within 18 months of enactment of the FSMA, will provide information on reportable and recalled foods to consumers through notices in grocery stores that have sold them.

The new requirements will require FDA to post on FDA.gov a one-page consumer-oriented summary of information sufficient to permit consumers to know whether they have purchased a reportable food. Fruits and vegetables that are raw agricultural commodities are exempted from this requirement. Only grocery stores that have 15 or more physical locations and have sold a reportable food that appears in a consumer summary must post the notices. They must do so within 24 hours of their FDA web posting and display them for 14 days.

Grocery stores must select at least one location and manner of posting the notices from a list of acceptable locations and manners that FDA is also tasked with developing.

Conclusion

We have seen that during the RFR’s first year, food industry awareness of the RFR’s requirements has spread rapidly, and as a result, the RFR has become an effective addition to the range of tools FDA has to prevent foodborne illness and protect public health. Agency efforts to heighten awareness of the RFR and increase its effectiveness will continue. We anticipate improved reporting as we continue our vigorous outreach to food facilities through federal, state, local, and foreign agencies to help us expand the positive effect of the RFR on the safety of the U.S. food supply.

Kathy Gombas is the acting Deputy Director for the Office of Food Defense, Communication, and Emergency Response at CFSAN. She has worked for the FDA for 5 years and is the Agency’s RFR Business Lead.

Howard Seltzer is the National Education Advisor in the Office of Food Defense, Communication, and Emergency Response at CFSAN and has been responsible for Reportable Food Registry outreach since the outset of the program. He has worked for FDA for 13 years.

>

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →