Shopping for Food Safety and the Public Trust: What Supply Chain Stakeholders Need to Know About Consumer Attitudes

Americans are confident about their ability to keep the food they eat safe but a new survey shows they don’t trust their neighbors, and they don’t really have a good feel for how widespread foodborne illness is. This perhaps not entirely surprising data comes from a new survey from the Michigan State University (MSU) Food Safety Policy Center (FSPC), whose mission is to promote the development and implementation of food and water safety policies that will ultimately improve human health by more effectively and efficiently reducing food- and waterborne illnesses.

The survey was conducted in an effort to better understand U.S. consumer attitudes about food safety—who they think should be responsible for it, who they think is most at risk, and even how severe they think the risks might be. The survey is unique in that it sought to represent the juggling of values that Americans face in food consumption through data on the socio-economic differences in consumer attitudes about the safety of the foods they purchase.

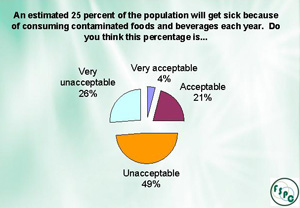

What has surfaced in the overall results is a few interesting dichotomies that may point to previously unexamined or unknown consumer knowledge gaps—and which ultimately may indicate ways that food safety stakeholders in government, industry and academia can provide consumers with more accessible, science-based consumer education. In general, the survey found that consumer confidence and optimism sometimes outpace statistical reality when it comes to the perception of how widespread foodborne illness is. For example, although there is little data tracking of how much of a toll foodborne illness takes on the nation, the latest study, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), indicates that foodborne illness sends some 325,000 people to the hospital each year, and results in the death of 5,000 people. When asked, most consumers in this survey underestimated the percentage of people who contract foodborne illness. According to the survey, only 10% of Americans say they got food poisoning in the past year—yet the 10-year-old CDC statistics estimate that a quarter of Americans suffer foodborne illnesses each year. It is possible that many Americans attribute incidences of illness to stomach flu.

Thus, it appears that, by and large, consumers know they get sick—but don’t know if it is foodborne illness. We can see that Americans tend not to attribute as many illnesses to food as they should and that people who get sick probably don’t know that the foods they eat are unsafe. Without that know-ledge, they can’t change their behavior. However, according to the results of this survey, when told how much foodborne illness is estimated to occur each year, they find it unacceptable. Consumers expect a greater degree of safety.

According to the survey results, the basis of some of the conflicting messages from consumers can be found in the fact that much of the food safety information they use to make decisions is inaccurate. In combination with other information, responses to the survey show very clearly that there is likely to be misinformation about food safety among consumers. The message for companies in the food supply chain? If you want consumers to remain loyal, you need to more effectively communicate information about the safety of your food products. In this article, we’ll highlight some of the MSU FSPC survey results and provide some insight into how the responses can provide direction to food supply chain companies and regulators in improving consumer education efforts to enhance consumer confidence.

About the MSU Food Safety Policy Center Consumer Perception Survey

The MSU FSPC survey results are based on nationwide telephone interviews with 1,014 randomly selected participants. It was conducted between Oct. 31, 2005 and Feb. 9, 2006, by the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research on behalf of the Food Safety Policy Center at Michigan State University. For results based on these samples, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum error attributable to sampling and other random effects is ±3 percentage points. Results were weighted to reflect the socio-demographic composition of the U.S. population.

The survey posed several questions regarding six food safety-related issues to determine current consumer attitudes, including:

• The level of public concern about food safety

• Attitudes about consumers’ own food safety behaviors

• Perceptions of how well food system actors protect foods

• Trade-offs between food safety and other food attributes

• Acceptability and willingness to pay to increase food safety

• Policy options

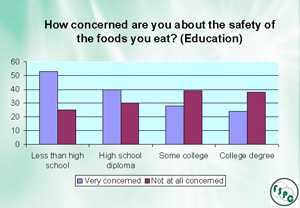

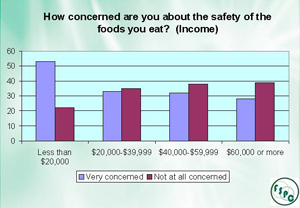

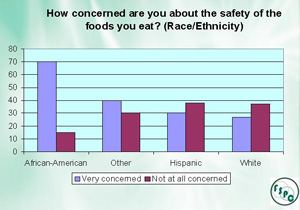

The survey also raised some warning flags about how race and class affect food safety issues. The survey indicated higher levels of concern about food safety among people with lower education levels, lower income levels and among African Americans.

Public Concern About Food Safety

In terms of the level of public concern about food safety:

• 70% are very or fairly concerned about pesticide and chemical residues (39% very concerned), only 22% are not at all concerned

• 68% are very or fairly concerned about foodborne illness (35% very concerned), only 22% are not at all concerned

• 63% of respondents are very or fairly concerned about the safety of the foods they eat (33% very concerned), 34% not at all concerned

• 52% are very or fairly concerned about additives and preservatives (24% very concerned), 38% are not at all concerned

• 50% are very or fairly concerned about antibiotics and hormones (28% very concerned), 41% are not at all concerned

• Even though 34% of respondents said they are not concerned about the safety of the foods they eat, only about one-fifth are not at all concerned about pesticide/chemical residues and foodborne illness

The survey shows that consumers are concerned about the safety of the foods they eat. More than two-thirds of respondents are very or fairly concerned about foodborne illness, and about half think about food safety when shopping at the grocery store (or think about food safety at least several times a week). While more than 40% of respondents admitted that they know little to “not much at all” about food safety (see below), it was the consumers who rated their knowledge more highly who were more concerned about the various aspects of the safety of the foods they eat.

The public is most concerned about pesticide and chemical residues and foodborne illness, with just half of the respondents concerned with antibiotics/hormones and additives/ preservatives. Even though 34% of respondents said they are not concerned about the safety of the foods they eat, 70% are concerned about pesticide/chemical residues and foodborne illness. A result of this level of public concern is may be evidenced by the huge growth in popularity of organic foods, which tout their pesticide- and chemical-free status.

The survey data indicate that consumer concerns about foodborne illness and pesticide/chemical residues may relate to very specific concerns involving food allergic individuals, or the age or gender of the individuals in the household, race and class. In addition to race and class (see “Highlighting Socio-economic Differences” section), respondents with someone in the household who is allergic to foods, females, middle-aged and older respondents, and respondents with someone over 65 years of age in the household are more likely to be very concerned about food safety than respondents without someone in the household who is allergic to foods, males, younger respondents, and those without someone over 65 years of age living in the household. After controlling for the age of the respondent, persons with a child under the age of 6 in the household indicated that they are more likely to be concerned about pesticide and chemical residues. Among the results:

• Respondents with someone in the household who is allergic to foods are more likely to be very concerned about food safety, antibiotics and hormones (69%), pesticides and chemical residues (48%), foodborne illness (45%), and additives and preservatives (36%) than those who do not have someone allergic in the household.

• Respondents with someone over 65 years of age in the household are more likely to be very concerned about pesticide and chemical residues (48% to 36%), and about foodborne illness (44%) than those who do not have someone over 65 years of age in the household.

• Females are more likely to be very concerned about pesticide and chemical residues (45%), and about foodborne illness (38% to 32%) than males

This data should be seen as an open invitation for food supply chain companies to communicate with customers about risks associated with foodborne illness in general, and in particular, targeting information to consumers in certain age, income and education groups, African-Americans, in households where food allergies are a concern, or even to consumers of the female gender. These are the consumer perceptions that directly impact confidence in the products they buy and to which they remain loyal. Processing, foodservice and retail operations may not want to talk about food safety with consumers because they don’t want people thinking about foodborne illnesses in association with their products, but our data shows that it is already on their minds.

Consumer Behaviors and Food Safety

In terms of how consumer behavior is influenced by food safety concerns, the survey found that:

• 54% of respondents said they think about food safety when shopping at the grocery store

• 46% thought about food safety the last time they ate at a restaurant

• 43% said they do not buy foods because they are likely to be unsafe

• 58% said that they know a lot or quite a bit about food safety, about one-third indicated they knew a little, and only 8% said they knew not much at all

Fifty-four percent say they think about food safety when grocery shopping and 46% say they consider it when eating out at a restaurant. These numbers are even higher for households in which someone has food allergies (67%). However, respondents between the ages of 55-64 are less likely to think about food safety when they shop for food (42%) than younger and older respondents.

As will be noted in the next section, 96% of survey respondents trust themselves to ensure the safety of the foods they eat. Ironically, the same people who believe so strongly in their own food safety abilities admit that they don’t have a good feel for how widespread foodborne illness is—and just 58% think they know a lot or quite a bit about food safety. Although from industry’s perspective talking about foodborne illness is always a delicate subject, it appears that there is a gap in consumer knowledge that can be addressed by making more information available through increased ad campaigns, labeling and other educational outreach efforts.

Perceptions of Food System Actors

In terms of who consumers perceive as responsible for food safety, the survey found that:

• Respondents believe that the federal government should be most responsible for insuring food safety (38%), followed by food processors and manufacturers (23%), consumers (11%), state government (10%), farmers (7%), grocery stores (4%), and restaurants (2%).

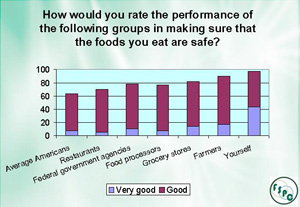

• 78% said that federal government agencies (FDA, USDA) were doing a good job of making sure that the foods they eat are safe; 78% for food processors and manufacturers; 89% for farmers; 82% for grocery stores; 69% for restaurants; 62% for average Americans; 96% for respondents

• 88% of respondents stated that the FDA and USDA were capable in making sure the foods we eat are safe; 91% for food processors and manufacturers; 92% for farmers; 93% for grocery stores; 95% for restaurants; 85% for average Americans; and 98% for respondents

• 78% indicated that the FDA and USDA were committed to food safety; 86% for food processors and manufacturers; 93% for farmers; 90% for grocery stores; 82% for restaurants; 80% for average Americans, and 97% for respondents

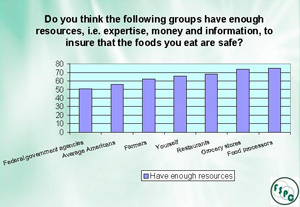

• Only 51% believe that federal government agencies have enough resources to insure food safety; 75% for food proc-essors and manufacturers; 62% for farmers; 68% for restaurants; 56% for average Americans; and 66% for respondents

Again, 96% of survey respondents trust themselves to ensure the safety of the foods they eat but that number drops to 62% when asked if they trust their average American neighbors to handle their food. Interestingly, consumers rank restaurants as the least responsible for food safety, although other studies have shown that a fairly large percentage of reported foodborne illness outbreaks are associated with foods served at the foodservice level. Even so, consumers give high marks to most of the food system actors in terms of rating whether they perceive these actors are doing a good job in terms of food safety. Respondents identify the federal government most often as the group they expect to keep food safe (38%). But while 88% say they think regulatory agencies—most notably FDA and USDA—are capable of and committed to keeping food safe for the public, only 51% feel the government has enough resources to do the job properly, indicating that nearly half of consumers believe that not enough is being invested in their protection. Respondents also believe food manufacturers have key responsibility to keep food safe (23%), but clearly think that processors have more capability to keep foods safe because they are perceived as having adequate resources to do so (75%).

However, that faith can be eroded with expanded media coverage around a foodborne illness outbreak or news stories about mad cow disease or avian flu. Phrases like “multi-state recall” and “thousands of tons of contaminated food,” fuel concerns among consumers who are becoming more vigilant and less trustful of those put in charge of their food chain.

That should be an action call to all food handlers and the government about the need to better communicate with the public about their food safety efforts. It doesn’t matter that professionals in the food industry know that all of these groups are taking actions to maintain and increase food safety for consumers. Outside of industry discussions and conferences, the average consumer doesn’t have a lot of knowledge about what’s being done to protect them and if the food handlers don’t give them that knowledge they will use information from the newspaper, the Internet and their friends and families to make decisions and judgments about product safety.

The lesson for the food industry is that it is equally important to communicate what is being done as it is to actually do it. If people know more about what is being done to protect their food, the level of trust in the products they buy—and the companies they buy from—will rise and their perceptions about food safety will more likely accurately reflect reality.

Acceptable Food Safety Trade-offs

In terms of trade-offs consumers are willing to make between food safety and other attributes, the survey found:

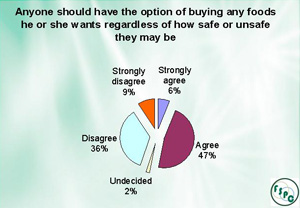

• Many respondents agreed that the government should ban foods that are less safe even if they have other attributes such as nutrition, taste and convenience than disagreed (47% /42%; 55% /38%; 64%/30%)

• Yet, the majority of respondents feel that anyone should be able to buy any foods regardless of how safe or unsafe they may be (52%)

While trust in the federal government’s ability to make the food supply as safe as possible is high but half of Americans surveyed say they don’t want the government to ban foods that may be deemed unsafe. Sometimes, it appears, we’re quite happy to accept unsafe food because it’s fresher, because it tastes better or because it’s part of our ethnic identity. We want to obtain the freedom to choose bundles of positives and negatives.

Acceptability and Willingness to Pay

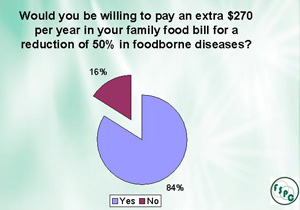

In terms of the level of willingness of consumers to pay for increased costs of food safety, the survey showed that most respondents find the percentage of foodborne illness (75%), the number of related hospitalizations (60%), and the numbers of deaths (68%) unacceptable. About three-quarters of respondents (74%) would be willing to pay an additional 5% to their food bill if foodborne diseases could be reduced by 50%; and 84% would be willing to pay an additional $270 (the equivalent to paying 5% more) to their food bill if foodborne diseases could be reduced by 50%.

The percentage of respondents willing to pay 5% more for increased food varied by the level of concern about food safety. The majority in all concern levels are willing to pay more, including those who are not concerned: Very concerned (85%); fairly concerned (74%); not too concerned (90%); not concerned (56%). The percentage of respondents willing to pay $270 more for increased food safety varied by the level of concern: Very concerned (86%); fairly concerned (89%); not too concerned (91%); not concerned (77%).

As mentioned, the surveyed consumers do identify themselves as the third most responsible group for food safety, behind government and food processors, though much less so (11%). The encouraging news is that while consumers rate themselves as fairly accountable for food safety, they are also willing to put that sensibility into action by paying more for food if foodborne diseases could be reduced by 50%.

Policy Options

In terms of what food safety related policy options consumers believe should be implemented, the survey found that:

• 96% of respondents state that labels should contain food safety information (52% strongly agree)

• While 71% disagree that imported foods are as safe as domestic foods, 95% of respondents indicate that imported foods should be subjected to the same inspection processes as domestically produced foods (56% strongly agree).

Again, the most compelling trend unearthed through this study is that U.S. consumers are largely confused about who to trust about food safety, as well as when and how they get sick. Ultimately, despite the fact that retailers, restaurants, processors and the government continue to make great strides to better protect products throughout the food chain, if consumers don’t believe their foods are safe, don’t know whose responsibility it is to make foods safe, or can’t differentiate foodborne illness from other diseases unrelated to food consumption, there is a problem. Similarly, it appears there is a knowledge gap with regard to imported food, which consumers indicate they do not feel are as safe as domestically produced product. For international food manufacturers, importers and distributors, it appears that consumers need to be educated about what steps are being taken to inspect and verify that imported foods are safe. If they aren’t, such food chain companies could be losing marketshare due to persistent, unfounded fears.

Highlighting Socio-Economic Differences

The survey data also shows statistically significant socio-demographic differences related to concern about the general safety of foods:

• Respondents with lower education levels are more likely to be highly concerned about food safety [less than high school diploma (53%), high school diploma (40%), some college (28%), and at least a college degree (24%)]

• Respondents between the ages of 35-44 and 45-54 are most likely to be concerned about food safety (42%/43% are very concerned and 74%/68% are concerned) than those be-tween the ages of 18-24, 25-34, 55-64, and 65 years or older

• African-Americans are more likely to be highly concerned about food safety (70%) than Whites, Hispanics, and respondents who indicated their ethnicity as other

• Lower income respondents (less than $20,000) are more likely to the have highest levels of concerns about food safety (53% are very concerned and 76% are concerned) than respondents with higher incomes

It can be suggested as a result of these and other socio-economic data included in the full MSU FSPC report that the survey raises some warning flags about how geography, race and class affect food safety issues. Respondents who live in the West, for example, are more likely to have low levels of concern about food safety (48% are not concerned, and only are 21% very concerned) than those who live in the Northeast, South, and Midwest. Why? The survey also indicates higher concerns about food safety among people with lower education and income levels, and among African-Americans. Why?

At this juncture, it isn’t clear why these concerns fluctuate among different classes and races. We don’t know if these groups have the same access to safer foods or are more exposed to out-of-date or potentially contaminated food than people in other areas. It may also have to do with unique experiences with food or negative perceptions about the people who handle their food. This data may indicate that it’s important for government and industry to get a handle on whether there is justice and equality in availability of highly safe food, and how that affects perception of their food safety efforts.

A Call to Action

The survey results show clearly that we don’t know enough about who is getting sick and we don’t know if foodborne illness is evenly distributed across the U.S., or even whether some groups are more able to protect themselves or are more protected against foodborne illnesses than other groups. The MSU FSPC study is just the beginning, and indicates a need for much more research into the relationship between food safety and consumer buying trends. The survey, available to the industry in its entirety at www.fspc.msu.edu, is just the first step in an effort to get a better handle on consumers’ fears and expectations about food safety but the message is clear: government and the food industry need to get the message out.

Craig Harris, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at Michigan State University, and is appointed in the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station and the National Food Safety and Toxicology Center. His work focuses on the social dimensions of food and agriculture, including food safety and food safety policy, and the interactions of agriculture with the environment. He is one of the faculty principals with the MSU Food Safety Policy Center.

Andrew Knight, Ph.D., is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at the MSU Food Safety Policy Center. His current research examines public perceptions of and policy implications surrounding biotechnology, food production systems, and food safety issues.

Michelle R. Worosz, Ph.D., is a Research Associate with the MSU Food Safety Policy Center. Her areas of expertise include the interactions between humans and the biophysical environment, science and technology, and policy and regulation of food and agricultural production.

.webp?height=200&t=1691503719&width=200)