The Signal to Start: How the FDA CORE Signals and Surveillance Team Evaluates and Identifies Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

Several tools and data sources are used in signal detection to evaluate genetic and epidemiologic information linked to foodborne outbreak investigations

In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established the Coordinated Outbreak Response and Evaluation (CORE) Network, which reorganized into the Office of Coordinated Outbreak Response, Evaluation, and Emergency Preparedness (CORE+EP) in 2024. This office serves as the agency's focal point for coordination, investigation, and evaluation of foodborne illness outbreaks. CORE+EP manages outbreak surveillance, response, communications, and post-response activities related to incidents involving multiple illnesses linked to FDA-regulated human food. Since 2011, CORE+EP has coordinated more than 1,100 foodborne illness outbreaks, with the earliest phases of the investigation being managed by the Signals and Surveillance (Signals) Team. This team plays a critical role in gathering, analyzing, and interpreting information to identify appropriate public health actions.

Signals is an interdisciplinary team of scientists that work together to support an effective food safety system. Signals operates with three objectives:

- Identify outbreaks

- Establish the outbreak's cause

- Determine whether there are actions FDA can take in response to the outbreak.

Signals collaborates with federal, state, and local partners to gather outbreak-related information, evaluate new incidents involving FDA-regulated products, and identify which incidents need additional coordination by one of CORE+EP's four Response Teams.

Highlighted below are real-world examples of key processes, tools, advancements, and challenges that showcase how Signals moves investigations from a faint signal to a distinct response designed to protect public health.

Outbreak Detection and Evaluation

Signals detects outbreaks as they emerge by searching for indicators that an outbreak has started to form. Indicators for an outbreak can vary depending on the pathogen, but a typical sign can include reports of multiple cases of an illness in one or more states. Signals works together with incident partners such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Outbreak Response and Prevention Branch (ORPB), federal and state partners, and several groups across FDA, to identify and analyze new and emerging foodborne illness clusters. Once an illness cluster has been identified, Signals analyzes relevant information to determine if the cluster is potentially associated with an FDA-regulated human food. Upon this determination, Signals and its partners develop a hypothesis for what FDA-regulated product or products may have caused the illnesses (Table 1) and may transfer the investigation to a Response Team for further coordination.

For most foodborne outbreak investigations, the initial information about an illness cluster and possible outbreak is laboratory-based. Because of advances in whole genome sequencing (WGS), the gold standard for evaluating genetic information, food safety investigators at FDA and CDC can classify, compare, and interpret large pools of genetic data. WGS information is useful to understand potential geographic clues and sources of contamination across the supply chain when evaluating this genetic information.1–4

State partners upload WGS results from illnesses to PulseNet, a national laboratory network connecting foodborne- and waterborne-related illnesses to detect outbreaks.5 CDC, the facilitator of PulseNet, notifies Signals of new outbreaks and any potential "signals" for foods that are regulated by FDA. An official investigation starts once a cluster has been identified and "coded" by CDC. This is followed by Signals working closely with CDC to identify the most likely food that is causing illness.

Tools for the Job

Several tools and data sources are used in signal detection to evaluate genetic and epidemiologic information linked to foodborne outbreak investigations. These are used for real-time surveillance of foodborne outbreak investigations:6

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

- GenomeTrakr WGS Network: A network of regulatory and non-regulatory laboratories that sequence foodborne pathogens and submit the genetic sequences to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Biotechnology Information Pathogen Detection Portal (NCBI PD), a publicly available, shareable database. Signals routinely utilizes NCBI PD for visualizing genetic clusters related to foodborne outbreaks that allows for real-time surveillance.7

- NCBI PD: Using the NCBI PD, Signals and FDA's bioinformatics experts can view phylogenetic trees with outbreak isolates and compare the relatedness of clinical and non-clinical isolates in each tree. This comparison is measured using SNPs analysis. Often, but not always, the phylogenetic tree of a defined cluster or outbreak can contain environmental or food isolates that may give some clues to the cause of the outbreak. The relatedness of clinical isolates to environmental or food isolates within the same phylogenetic tree can provide geographic leads, insight into possible infectious sources, and potential routes of contamination.3,4

- System for Enteric Disease Response, Investigation, and Coordination (SEDRIC): Signals uses this system for visualizing epidemiologic data and determining if an FDA-regulated product may be responsible for the outbreak. SEDRIC compiles data from national surveillance systems, laboratory investigations, and public health and regulatory agencies at the state and federal level. It is used to view epidemiologic curves, outbreak charts, exposure information, and historic or current surveillance data in a single platform.

- Internal FDA databases: In addition to NCBI PD and SEDRIC, internal FDA databases are also used to assist in signal detection and hypothesis generation. These databases allow Signals to research past recalls and consumer complaints, as well as analyze sampling data and manufacturing or distribution practices for specific commodities. All these databases and tools are combined to help the Signals team investigate foodborne outbreaks and triage incidents to Response Teams accordingly.

Activating Response Coordination

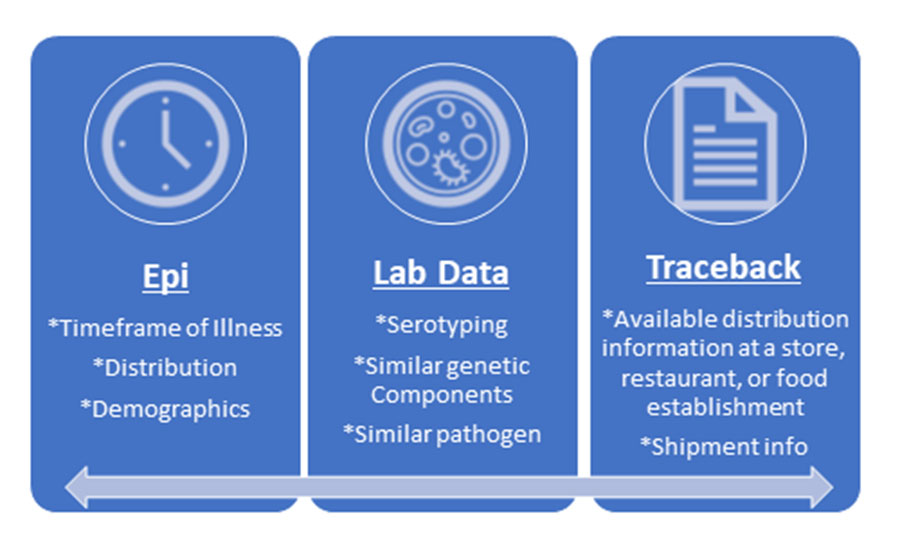

Signals is the triage entity for foodborne illness outbreaks potentially linked to FDA-regulated human foods. During outbreak investigations, public health and regulatory authorities collect three types of data to confirm the food item responsible for, or associated with, the outbreak: epidemiologic, traceback, and laboratory information (Figure 1).8,9 In addition to laboratory and traceback efforts, Signals plays an important part in analyzing epidemiologic data, such as population, place, and time, that show potentially impacted demographics of an outbreak investigation. Strong data from these sources enable CDC and FDA to identify confirmed or suspected sources of outbreaks.

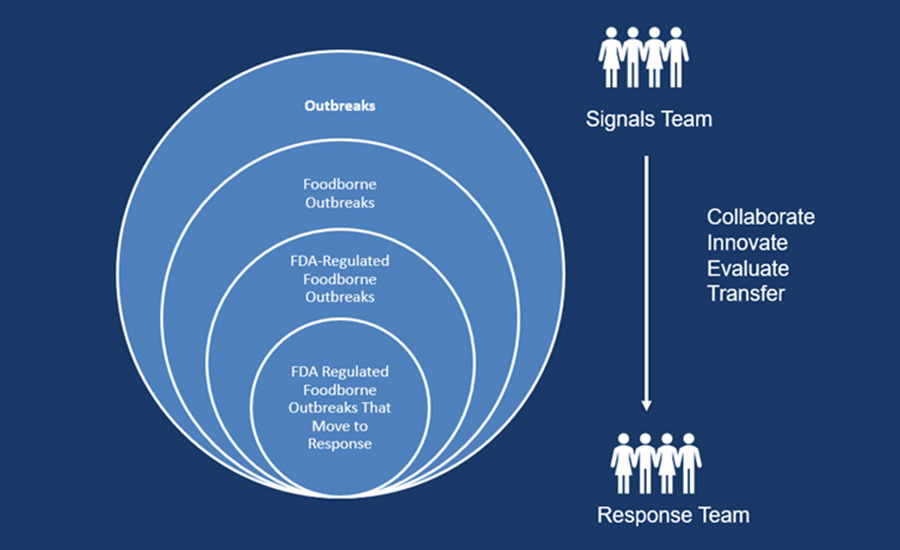

Once an FDA-regulated food product has been identified as a suspect vehicle for the outbreak, Signals evaluates several factors (Table 2) that can initiate a transfer to a Response Team. When an incident is slated to be transferred to a Response Team for further FDA action, Signals develops a clear list of objectives, outlines potential next steps in the investigation, and compiles a list of incident partners to include in response activities moving forward. Of the foodborne outbreaks known to be caused by an FDA-regulated product since 2020, slightly more than one in three (38 percent) have sufficient information for a transfer from Signals to a Response Team (Figure 2). Signals serves as the first-line workers and decision-makers for the early stages of outbreak response, and this process allows FDA to allocate resources accordingly and judiciously for outbreak response efforts.

Not all evaluations conducted by Signals result in a transfer. For example, outbreaks that have already ended or are linked to non-FDA regulated products, such as those regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), are not transferred to a Response Team for further coordination. There are also instances when Signals evaluates an incident in which a vehicle cannot be identified initially. The outbreak may have occurred over the course of several years, and multiple evaluations may be necessary before the incident is transferred and solved. This often occurs with outbreaks of Listeria monocytogenes.

The Ever-Changing World of Food Safety

CORE's establishment in 2011 created a collaborative space for FDA and partners to connect foodborne illness and food safety. From engagement on the international stage to honing tactics for nationwide investigations, Signals has routinely adapted to the changes in the food safety landscape.

International Collaboration

During international foodborne outbreak investigations, Signals routinely collaborates with international health and regulatory partners to share investigational information and coordinate food safety response activities involving imported foods. Recent international engagements have yielded partnerships with health and regulatory agencies from Canada, England, France, Mexico, Scotland, Singapore, and Sweden, with continued efforts to engage additional international partners.

In 2019, Signals collaborated with Canadian partners to investigate an ongoing outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes linked to enoki mushrooms.10 This international collaboration laid the foundation to conclude imported enoki mushrooms as the outbreak cause and initiate product recalls in several countries around the world. The investigation resulted in:

- Modernized database use: A 2016 enoki mushroom isolate uploaded by Canadian partners to the NCBI PD database in 2020 proved to be a WGS match to an outbreak strain in the U.S., as well as other clinical and enoki isolates around the world.

- Streamlined source identification: CDC's investigation found that 55 percent of cases (12 of 22) reported a variety of mushrooms, including enoki. Additional sampling efforts and collaboration among state, federal, and international partners led to more positive product samples that also matched the outbreak strain.

- Strengthened international awareness: Public health alerts and recalls warned the international community of the outbreak and import actions against enoki mushrooms imported from South Korea.

Complaint-Driven Incidents

In recent years, consumer-reported information to FDA, including information used to develop data sets on foodborne illnesses, have been critical for Signals to decipher and analyze. In contrast with traditional outbreaks detected by laboratory-based surveillance and epidemiologic information, complaint-driven incidents are sparked by outbreak information submitted directly by consumers, healthcare providers, industry members, public health officials, or other submitters.11 To help understand these outbreaks and to provide an effective response, Signals has developed a complaint evaluation process to assess potential complaint trends.

In June 2022, Signals initiated an investigation into an adverse event cluster using information gathered from the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition's Adverse Events Reporting System, now known as the Human Foods Complaint System.11 Analysis of consumer complaint reporting through this system showed:

- Thirty-five gastrointestinal-associated illnesses and 20 hospitalizations after consuming Brand A French Lentil and Leek Crumbles12

- Vehicle signals for sacha inchi powder and tara protein flour as ingredients of interest without a specific source of contamination

- A need for records review and CORE Response actions, which helped initiate a recall of the suspect products, further reducing the possibility of additional adverse events.

Sample-Initiated Retrospective Outbreak Investigations (SIROIs)

Like complaint-driven incidents, SIROIs follow a different process than traditional outbreaks. SIROIs begin with a bacterial isolate from a positive product or environment sample, which is then linked by WGS to clinical isolates.13 In collaboration with CDC, Signals evaluates these instances and identifies candidates for further epidemiologic and traceback investigations to confirm the link between the illness and the suspect vehicle.

SIROIs provide the benefit to quickly identify potential links between food production environments and human illness. Subsequently, this allows for control measures and prevention of additional illnesses earlier than the traditional pathway that begins with identification of a cluster of related clinical illnesses and continues with a subsequent epidemiologic investigation to identify a vehicle hypothesis.

In May 2022, Signals and FDA's bioinformatics experts identified a clinical cluster of Salmonella Senftenberg isolates in the NCBI PD database that were genetically related to several peanut butter and environmental isolates collected between 2014 and 2017. This relationship proved to be a successful application of SIROI, which prevented additional illnesses and uncovered:

- Historical data: Information from internal databases suggested previous and possible ongoing contamination issues at a specific peanut butter manufacturing firm. This finding supported the genetic analyses and further suggested that the firm in question was the possible source of contamination.

- Use case for collaborative tools: With information obtained from internal FDA databases, NCBI PD, SEDRIC, and interviews with clinical cases, Signals was able to pinpoint a specific brand of peanut butter as the suspect vehicle for the outbreak.

- Effective detection and recall efforts: Further investigation of epidemiologic data, WGS information, and previous inspectional findings provided evidence to confirm peanut butter as the cause of illnesses. The ability to leverage multiple detection tools led to a recall of contaminated product and the eventual removal of this shelf-stable product from the market and from consumers' homes.

Takeaway

Food safety continuously evolves, and Signals has adapted to advancing technologies and emerging threats. This team helps safeguard the nation's food supply through early detection, collaboration, innovation, and process improvements related to foodborne outbreak investigation and regulatory response. Signals continues to face new challenges head-on in lockstep with long-standing federal, state, local, and industry partners.

The team's expertise in evaluating quantitative information, measurable evidence, and historical relevance determines the signals that ultimately align to solve an outbreak and protect consumers. Information-sharing, transparency, and a proactive approach contribute to improvements in signal detection, evaluation, and response to foodborne outbreaks. By working together, CORE+EP and all the investigative partners continue to make progress to identify outbreaks as quickly as possible, determine their cause and transmission routes, and apply lessons learned to better inform future investigations.

References

- Brown, B., M. Allard, M.C. Bazaco, J. Blankenship, and T. Minor. "An Economic Evaluation of The Whole Genome Sequencing Source Tracking Program in The U.S." PLoS One 16, no. 10 (October 2021): e0258262. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34614029/.

- Jackson, B.R., C. Tarr, E. Strain, et al. "Implementation of Nationwide Real-Time Whole-Genome Sequencing to Enhance Listeriosis Outbreak Detection and Investigation." Clinical Infectious Diseases 63, no. 3 (August 2016): 380–386. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27090985/.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Examples of How FDA Has Used Whole Genome Sequencing of Foodborne Pathogens For Regulatory Purposes." Current as of February 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/whole-genome-sequencing-wgs-program/examples-how-fda-has-used-whole-genome-sequencing-foodborne-pathogens-regulatory-purposes.

- FDA. "Whole Genome Sequencing Program." Current as of August 30, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/science-research-food/whole-genome-sequencing-wgs-program.

- Tolar, B., L.A. Joseph, M.N. Schroeder, et al. "An Overview of PulseNet USA Databases." Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 16, no. 7 (July 2019): 457–462. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31066584/.

- FDA. "About the CORE Network." Current as of January 8, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/about-core-network.

- Blessington, T., A. Grant, T. Greenlee, A. Pightling, and S. Viazis. "The Value of the National Center for Biotechnology Information's Pathogen Detection Website in Identifying Geographic Clues to Aide Outbreak Investigations." International Association for Food Protection (IAFP) Annual Meeting 2022, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. https://iafp.confex.com/iafp/2022/onlineprogram.cgi/Paper/29268.

- Irvin, K., S. Viazis, A. Fields, et al. "An Overview of Traceback Investigations and Three Case Studies of Recent Outbreaks of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Infections Linked to Romaine Lettuce." Journal of Food Protection 84, no. 8 (August 2021): 1340–1356. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33836048/.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Steps in a Multistate Foodborne Outbreak Investigation." January 30, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/foodborne-outbreaks/investigation-steps/index.html.

- Pereira, E., A. Conrad, A. Tesfai, et al. "Multinational Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes Infections Linked to Enoki Mushrooms Imported from the Republic of Korea 2016–2020." Journal of Food Protection 86, no. 7 (July 2023): 100101. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37169291/.

- FDA. "Human Foods Complaint System (HFCS)." Current as of July 14, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/food/compliance-enforcement-food/human-foods-complaint-system-hfcs.

- Bazaco, M.C., C.K. Carstens, T. Greenlee, et al. "Recent Use of Novel Data Streams During Foodborne Illness Cluster Investigations by the United States Food and Drug Administration: Qualitative Review." JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 11 (February 2025): e58797. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40020044/.

- Wellman, A., M.C. Bazaco, T. Blessington, et al. "An Overview of Foodborne Sample-Initiated Retrospective Outbreak Investigations and Interagency Collaboration in the United States." Journal of Food Protection 86, no. 6 (June 2023): 100089. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37024093/.

Ashley Grant, M.P.H. is an Epidemiologist in the Office of Coordinated Outbreak Response, Evaluation, and Emergency Preparedness (CORE+EP) in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) Human Foods Program (HFP).

Tyann Blessington, Ph.D., M.S., M.P.H. is a Regulatory Scientist at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.

Daniela Schoelen, Ph.D., M.P.H. is a Biologist at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.

Stelios Viazis, Ph.D. is a Consumer Safety Officer at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.

Cary Chen Parker, M.P.H. is a Supervisory Consumer Safety Officer at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.

Anders Evenson is a Health Communications Specialist at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.

Kellen Stuart is a Health Communications Specialist at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.

Jennifer Beal, M.P.H. is a Supervisory Consumer Safety Officer at CORE+EP in FDA's HFP.