A Food Industry Perspective on The Benefits and Barriers of WGS for Pathogen Source Tracking: The Sequel

Whole genome sequencing is gaining traction within the food industry, but advancements in technology, regulatory clarity, standardization in sequencing, and results interpretation are needed

In 2019, a workshop was convened to explore the food industry's perspectives on the benefits and challenges associated with the use of whole genome sequencing (WGS) for pathogen source tracking. To assess developments since the original workshop, a follow-up survey was conducted in 2024, receiving responses from 18 companies including major industry players.

The findings reveal that while WGS is predominantly utilized for pathogen source tracking, there has been an increase in its application for strain identification and characterization. Despite the growing adoption of WGS, challenges remain, including time to results and lack of standardization in sequencing methodologies and thresholds for results interpretation. Furthermore, legal uncertainties surrounding data-sharing continue to pose significant hurdles.

The survey also highlighted the importance of training and the need for better validation practices in WGS implementation. Although an ISO standard was issued in 2022 describing the minimum requirements for generating and analyzing WGS data of bacteria, translation of the method technicalities and its reliability to food industrials remains challenging.

Overall, while WGS is gaining traction within the food industry, further advancements in technology, regulatory clarity, standardization in sequencing, and results interpretation are essential for its broader acceptance and effective use in ensuring food safety.

Workshop Background and Surveys

To gain insights into the food industry's perspective on the benefits and challenges of WGS for pathogen source tracking, a workshop was held in 2019. Prior to the workshop, a survey was distributed to various companies. The results of this survey and a summary of the discussions were published in Food Safety Magazine.1

One outcome from the 2019 workshop was the need for a network of interested parties, leading to the creation of an online forum with quarterly meetings. This forum has grown to more than 70 participants from over 40 different companies, including people from the food industry, service providers, and academia. To evaluate potential changes and developments that have occurred in the five years since the workshop, a follow-up survey was sent out in 2024. Answers were received from 18 companies. Six companies that completed the survey had not attended the 2019 workshop, while the remaining respondents were from companies where either that person or another representative of their company had participated in the workshop.

It should be noted that the companies contributing to the forum and this article represent a small segment of the food industry and are likely to have a positive bias regarding WGS, since they attended the WGS workshop or are members of the forum. Therefore, this article does not presume to reflect the perspectives and practices of the food industry as a whole.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

WGS Use by the Food Industry

Of the 18 respondents, four are not using WGS at their companies. In comparison, 16 of 18 companies participating in the 2019 survey did use WGS at least infrequently. When WGS is used, it is still mostly for pathogen source tracking (used by 14 companies), but other applications such as strain identification (used by nine companies) and strain characterization (used by six companies) have increased since the 2019 survey, where only four companies indicated the use of WGS for strain characterization. This increase is potentially linked to a better understanding and use of the information obtained by WGS. It can help to better define strain characteristics that lead to spoilage or resistance against cleaning regimes, enabling more targeted and risk-based actions.

Clearly, WGS is now considered as a routine tool used when other typing tools do not provide the required granularity. However, simpler subtyping tools continue to be used, such as serotyping (used by 11 companies) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (used by eight companies). The use of ribotyping declined: in 2019, five companies were using it, whereas only one company still uses it according to the 2025 survey. There may be several reasons why the use of other typing tools such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or ribotyping has decreased, potentially including changes in regulatory approaches (e.g., moving from PFGE to WGS for outbreak investigations), availability of external services in terms of time to results, or simply method availability (e.g., PFGE equipment may no longer be available in some regions) and the low cost for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. For the latter, in addition to the lower cost, it has the advantage of being a validated method that is accredited in many laboratories. However, it should be noted that although MALDI-TOF can provide rapid results at genus level (e.g., Salmonella spp.), it is not suitable for higher discriminations at species or strain level.

WGS is only one of the genomic tools used by companies; ten companies confirmed the use of additional genomic approaches. Of those using other approaches, five companies use metabarcoding, seven use metagenomics, and one uses transcriptomics. The respondent who uses both WGS for pathogen source tracking and strain characterization also employs transcriptomics. These other genomic approaches are not used for pathogen source tracking, but rather for evaluation of microbial communities without the need for culturing.

Models of Implementation

Sequencing

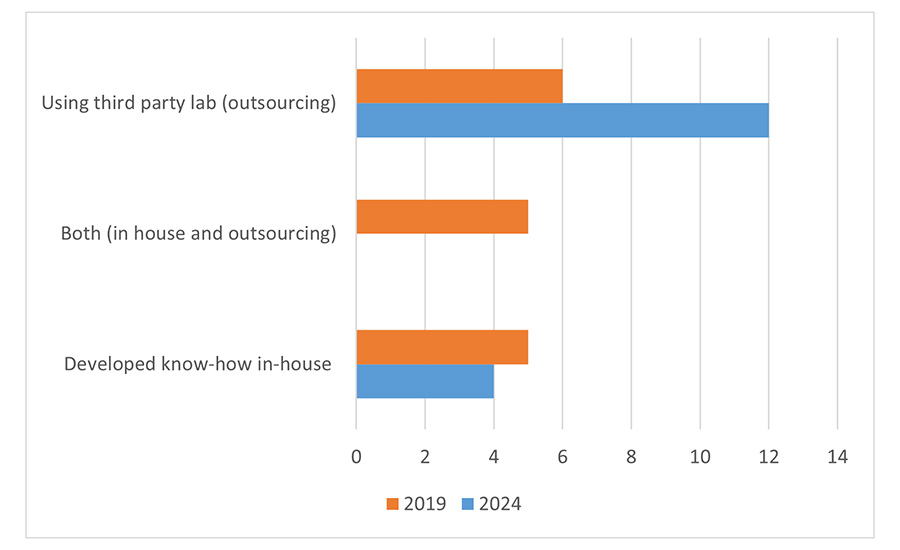

Similar to the 2019 survey, most companies are outsourcing their sequencing (Figure 1). A combination of insourcing and outsourcing was used by two companies. Two companies are performing WGS internally, with only one employing a decentralized approach. This indicates that WGS has not yet been implemented at the point of use, such as in the factory or local laboratory.

When sequencing is outsourced, a decentralization approach is favored by seven companies out of 12.

Bioinformatics

Another question asked where bioinformatics analysis for pathogen source tracking is carried out. In 2024, there was a notable shift toward outsourcing, while in 2019, a combination of performing analyses in-house and outsourcing was reported (Figure 2). The combination of in-house and outsourcing—a model chosen by five companies in 2019—was no longer deployed in 2024. Most companies are outsourcing in one central location (seven companies), while five companies use multiple locations for outsourced analysis. Four companies are carrying out bioinformatics analysis in-house, with the majority in one location (three companies) and only one company in more than one location.

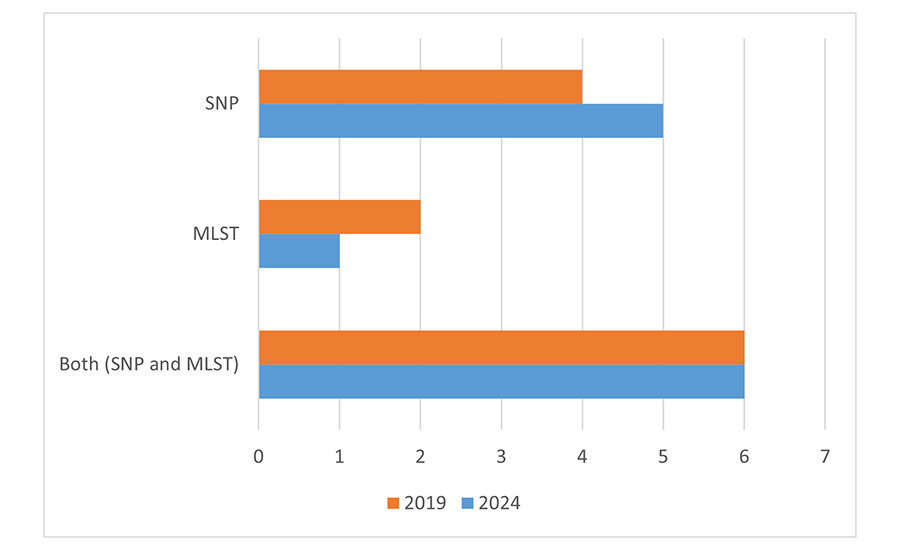

Regarding the approaches used for bioinformatics analysis, there was no significant change from 2019. Most companies are using either single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) or a combination of SNP with core/whole genome multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (Figure 3). A notable percentage of respondents, five occurrences (31 percent), expressed uncertainty ("Don't Know") regarding the method used. Publicly available algorithms are most used (six companies). Commercially available platforms were used by three companies, and only two developed their own tools.

To ensure the accuracy of WGS results in food industry operations, companies employ various approaches to validate the sequencing and/or bioinformatics part. When WGS is outsourced, there is a strong reliance on the external service providers to ensure the validity of the results. To illustrate, from 17 respondents, ten companies rely on third-party validation. Three companies mention that ISO 23418:20222 must be followed and/or their lab has to be accredited for this standard.

Different approaches are seen when companies perform validation internally, including a comparison between WGS and alternative subtyping technologies; sequencing using two technologies; and comparing results across a defined number of isolates, proficiency tests, and published peer-reviewed papers. Good laboratory practice is still a foundational requirement in the laboratory to ensure the purity and correct identification of an isolate (especially in the case of Listeria monocytogenes) so that WGS is only performed on individual isolates of interest.

Benefits of WGS for Pathogen Surveillance and Tracking

The 2024 survey confirmed the observations made in 2019 regarding the discriminatory power of WGS in the context of pathogen surveillance and tracking. The ability to demonstrate the genetic relatedness between strains is of paramount importance for the food industry. The high resolution of genetic data is essential for identifying instances of laboratory cross-contamination and for distinguishing transient from persistent strains of pathogens.

Although not all companies differentiate between resident and transient strains, eight companies (62 percent) reported that they do make this distinction. This percentage is comparable to the 2019 survey. Appendix 1 of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) Preventive Controls for Human Food Guidance describes the link between resident strains and persistence in the environment as follows: "Once an environmental pathogen has become established as a 'resident strain,' there is a persistent contamination risk for foods processed in that facility."3 "Persistent strains" are defined by CDC as "strains causing illnesses consistently over a long time."4 Since the 2024 survey was conducted in the food industry, it is unclear if the term had been used as defined by CDC or is linked to the persistent contamination risk outlined by FDA.

Limitations and Hurdles of WGS for Pathogen Source Tracking

The most frequently cited limitations and hurdles for the use of WGS by the food industry in the 2024 survey are:

- Time to result (time delay)

- Lack of sequencing standardization, with methods evolving constantly

- Lack of clear thresholds for data interpretation

- Challenges in result interpretation and a high level of expertise required for interpretation

- Uncertainty of legal implications.

These limitations are very similar to those mentioned in the 2019 workshop and survey. Some of them have been outlined in 2024 in more detail:

- Absence of internationally recognized consensus on cut-off values or relatedness

- No agreed validation standards

- Difficulties in comparing different methodologies, such as core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) and SNP

- Difficulties in isolate and data management, particularly regarding how to ship isolates to the proper laboratory, handle the paperwork, store the data (considering the price and infrastructure required), ensure the confidentiality of the sequences or analyses performed, and clarify data ownership (e.g., Nagoya Protocol)

- The lack of global availability to maintain reliable and stable bioinformatics expertise in a constantly evolving field

- The lack of service providers globally, and a lack of trusted partners to provide sound analysis

- Missing legal context regarding the adoption and use by regulators, linked to the potential consequences of matching isolates in retrospective studies.

Uncertainty of legal implications remains one of the main hurdles of using WGS and in data-sharing with regulators, which could lead to confidentiality breaches and excessive regulatory intrusion into food safety practices. This concern is compounded by the potential for mandatory data-sharing, which could result in misinterpretation and erroneous actions. Additionally, legal issues represent a significant barrier, including the risk of legal actions and incorrect product recalls due to a lack of holistic and comprehensive understanding of incidents, which could negatively impact brand reputation. Another major concern in this area is the potential consequences related to past incidents and the discordance with outdated methods. For only 19 percent of respondents, regulatory implications would not affect their use of WGS for pathogen source tracking.

Since 2019, 47 percent of respondents have observed no change in regulatory interest in WGS. For the remaining 53 percent, regulators are increasingly advocating for the testing and sharing of data, even though it is not mandated by law. Whereas in the U.S., FDA is recommending the use of WGS in view of pathogen findings, the EU passed a new regulation in February 2025 (EU 179/2025)5 on the use of WGS during outbreaks. The latter requires the submission of any isolates potentially related to an outbreak to authorities for performing WGS. Besides that requirement, there is no obligation for industry to implement WGS. All survey respondents agreed that government agencies should only request isolates or WGS data in the case of a defined outbreak, which mirrors the current EU legislation.

Regarding WGS data-sharing with public health and regulatory agencies, the majority (nine of 18) preferred sharing data within a defined network of government agencies, such as partner states within the EU, to help ensure data security and controlled access among trusted entities. A smaller group (three of 18) favored keeping the data within government agencies only, to prioritize data confidentiality and internal use. Five respondents supported sharing data publicly in real time, to promote transparency and immediate access for researchers and the public. Only one respondent preferred sharing data publicly with a timed delay, such as one year, to balance public access with a period of restricted use. These responses reflect diverse perspectives on balancing data security, confidentiality, and public accessibility in managing WGS data.

In general, it was acknowledged that WGS is gaining broad acceptance and use by regulatory agencies worldwide, particularly for outbreak investigations, making it the preferred method due to its discriminatory power. This approach has resulted in multiple cases linking resident or persistent strains over many years within environments or products, thereby helping to prevent or minimize foodborne illnesses and leading to more recalls.

To ensure data privacy when utilizing WGS, most respondents (53 percent) protect themselves through non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and confidential disclosure agreements (CDAs). The selection of trusted partners and the establishment of well-defined ways of working are crucial for maintaining data security from transfer to interpretation. Most respondents ensure data anonymization and secure transfer via file transfer protocol, avoiding uploads to external or public databases. Additionally, some respondents outsource the sequencing process while conducting data analysis internally to enhance security.

There is a consensus among respondents that training is necessary across various levels and functions, particularly in understanding WGS tools and their applications. Basic education on the benefits of WGS compared to other techniques is recommended, along with targeted technical training for sequencing and bioinformatics, including the development of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for sample preparation and in-depth understanding of the results. The requirement for auditor training for external service providers is highlighted as a gap, and the importance of proficiency testing schemes to keep staff updated on the latest advancements in WGS is emphasized.

Outlook for Future WGS Application

Future developments and advancements in WGS technology that are likely to positively assist the food industry include reducing the costs and time required to obtain results and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for the analysis of metadata and sequences. This includes advancing the development of more rapid and streamlined protocols, such as one-step devices or "lab-on-a-chip" technologies. Linking WGS to environmental management systems and predictive models using AI could improve monitoring and control measures.

A broader use of WGS may also facilitate a more risk-based approach to managing bacteria, including persistence in the processing environment, evaluation of resistance to cleaning and disinfection programs, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence factors. Further standardization of WGS applications specifically for the food industry is necessary.

References

- Klijn, A., D. Akins-Lewenthal, B. Jagadeesan, L. Baert, A. Winkler, C. Barretto, and A. Amézquita. "The Benefits and Barriers of Whole-Genome Sequencing for Pathogen Source Tracking: A Food Industry Perspective." Food Safety Magazine June/July 2020. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/6696-the-benefits-and-barriers-of-whole-genome-sequencing-for-pathogen-source-tracking-a-food-industry-perspective.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). "ISO 23148:2022: Microbiology of the food chain—Whole genome sequencing for typing and genomic characterization of foodborne bacteria—General requirements and guidance." Ed. 1, June 2022. https://www.iso.org/standard/75509.html.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "FDA Publishes Revised Draft Introduction and Appendix to the Preventive Controls for Human Food Guidance." Current as of May 30, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/hfp-constituent-updates/fda-publishes-revised-draft-introduction-and-appendix-preventive-controls-human-food-guidance#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Food%20and%20Drug%20Administration%20%28FDA%29%20has,Food%3A%20Draft%20Guidance%20for%20Industry%E2%80%9D%20%28PCHF%20Draft%20Guidance%29.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Reoccurring, Emerging, and Persisting Enteric Bacterial Strains." December 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/foodborne-outbreaks/php/rep-surveillance/index.html.

- European Commission of the European Union. "Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/179 of 31 January 2025 on the collection and transmission of molecular analytical data within the frame of epidemiological investigations of food-borne outbreaks in accordance with Directive 2003/99/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council." EUR-Lex Document 32025R0179. January 31, 2025. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2025/179/oj/eng.

Adrianne Klijn, Ph.D. leads the Analytical Microbiology Platform for Nestlé.

Aurelien Maillet, Ph.D. leads the microbiology, molecular biology, and genomics team for Mars Global Services R&D Solutions.

Bala Jagadeesan, Ph.D. is Senior Specialist in the Food Safety Microbiology group at Nestlé Research in Switzerland.

Caroline Barretto, M.S. is R&D Expert Bioinformatics at Nestlé Research in Switzerland.

Francois Bourdichon, Ph.D. coordinates the network of analytical entities of Sodiaal International.

Jerome Combrisson, Ph.D. leads the Center of Expertise in Applied Analytical Sciences for Mars Global Services R&D Solutions.

Leen Baert, Ph.D. leads the whole genome sequencing requests for source tracking within Nestlé.

Martin Wiedmann, Ph.D. is the Gellert Family Professor of Food Safety at Cornell University, where he leads a research and extension program.

Anett Winkler, Ph.D. supports all Cargill businesses in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa for microbiological and food safety related topics.