Allergen Control

Successful allergen control requires close attention to detail

Preventing contamination requires careful planning and regular evaluation of the plan.

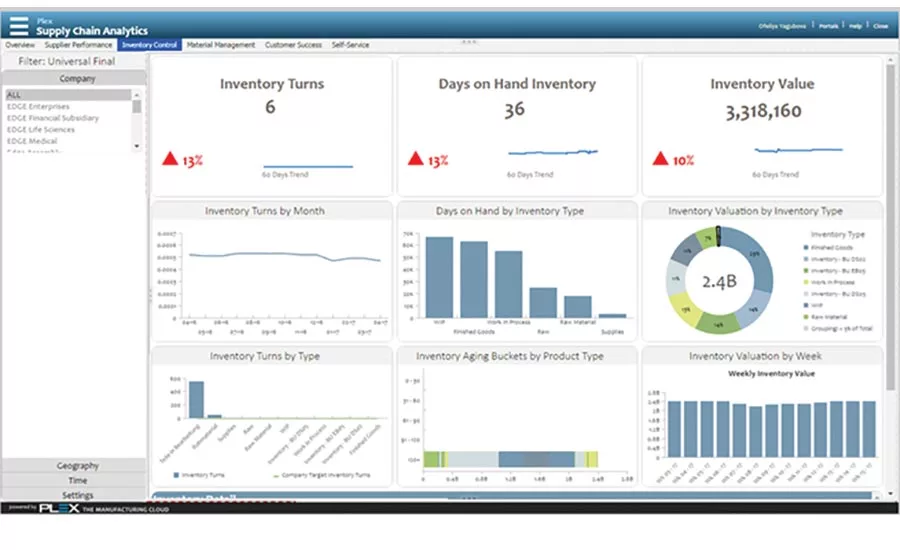

A screenshot of Plex Software’s upcoming IntelliPlex Supply Chain Analytics application, which allows for management of allergens in inventory.

Proper processing of fish, whether as a product or an ingredient, can help food processors avoid possible cross-contamination of products that should be fish-free. Credit: Anutik.

As an ingredient in a wide range of products, soy can lead to cross-contamination issues in food processing plants if not carefully managed. Credit: ithinksky.

David Clifford spends a lot of time thinking about peanuts.

And milk, eggs, tree nuts, wheat, soy, fish and seafood.

If those items sound familiar, it’s because they’re the eight categories of food allergens. As food safety manager for Nestlé Zone Americas, Clifford has to consider them all as the company implements and executes its allergen control plans.

While other processors may not necessarily operate on the scale of Nestlé, Clifford does offer a piece of advice that a processor of any size can use as a starting point.

“It doesn’t matter what facility you’re in,” Clifford says. “You still have to do label control, you still have to do material control, you still have to do recipe management, you have to have good practices in how you’re putting materials into process, and the hygienic conditions that you’re managing in the process and the cleaning you’re applying.”

As processors look to implement or improve allergen control plans, all of those universal concepts come into play. If you explore each in an in-depth manner and implement sound plans company-wide, an allergen control plan begins to take shape. Then, it can be modified as necessary from plant to plant or even within a plant based on the needs of a particular facility.

Think of it like this: At the corporate level is the master plan with broad guidelines for how allergen control should be handled. But as you move down the line to the individual production line level, the plan becomes more and more detailed as it takes into account what products are being made, what ingredients they entail, where they are located in relation to ingredients, how they are cleaned and so on.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

As an example, the master plan might say “avoid producing products that contain allergens and non-allergenic materials together.” But at the production level, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you can’t use the same line for a product with milk and one without; you just need to be sure you have a good plan in place for preventing the non-milk product from being contaminated.

“At the shop floor, employees know what works best for their operation,” says Clifford. “The manufacturing sites are required to take those requirements and create an implementation plan locally that accounts for specific needs of their product category line design, and factory layout—all must be considered.”

In the case of Nestlé, this would mean that a coffee production facility might have an allergen control plan that is almost entirely different from one that produces frozen foods. While the overall philosophy and the goals are the same across the company, the implementation at the production level is driven by the demands of the products produced and the facilities in which they are produced.

This applies across all the areas mentioned, and as Clifford and others say, each of these areas of concern requires attention to different details. How much attention you pay to those details can be the difference between successful allergen control and scrambling to correct a big mistake.

Label control

For consumers in the grocery store, labeling seems like a pretty simple thing: The box of cereal says it was made in a facility that processes peanuts, so it’s not a good choice if a child has a peanut allergy. Properly labeling products is a step that manufacturers can take to help avoid a disastrous situation, but from the processor’s point of view, it cannot be considered a solution by itself, says Frank Massong, vice president of regulatory and technical services for Allergen Control Group Inc.

“It’s probably the most misused and misunderstood method used by manufacturers to provide extra caution to those persons who have severe allergies,” says Massong. “It is not intended to replace good manufacturing practices and the responsibility companies have to deliver on those good manufacturing practices.”

Properly labeling products is a step that manufacturers can take to help avoid a disastrous situation, but ... it cannot be considered a solution by itself.

– Frank Massong

Labeling for allergens is a relatively new concept, according to Steve Taylor, PhD, co-director of the Food Allergy Research and Resource Program at the University of Nebraska. In fact, so is allergen control; as Taylor points out, even as recently as the early 1990s, it was generally confined to manufacturers of products such as infant formula.

But it’s here to stay, which means vigilance in labeling is as well. In most cases, labeling goes through a pretty intensive checking process due to regulatory and nutrition requirements, and allergen control information is built into that process somewhere along the line.

But that doesn’t stop the simplest problem, Taylor says: a product being mistakenly put in the wrong packaging.

“The industry gets that 99.9999 percent right. But when they make a mistake, it’s typically a bad one, because you end up with the peanut butter granola bars in the oatmeal and raisin box,” says Taylor. “If the consumer doesn’t figure that out, that’s a pretty healthy dose of undeclared allergens going in their mouth.”

At Nestlé, labeling goes through a review process which involves both regulatory checks and quality checks. Within the quality group are allergen specialists who are involved with the workflow to assure accurate allergen information.

“It’s a comprehensive workflow with a lot of checks and balances and a lot of overlap with what is being looked at,” says Clifford.

Material control

When a processor puts an allergen control plan in place, it will ideally cover everything from raw materials coming in the door to the finished product going out the door. Within a production facility, everything should be accounted for in the allergen control plan and set up in a way to most limit your potential exposure to contamination.

But what about raw materials before they come in the door?

Raw materials are a potential weak spot in an allergen control plan due to factors beyond the processor’s control. As an example, Taylor mentions a situation several years ago when cumin from India was contaminated with peanuts. The reason for the contamination was that farmers in India who didn’t have much practical knowledge of allergen control—or the resources to handle it properly—were growing peanuts and cumin in close proximity.

Or, consider how blueberries ended up being contaminated with pistachios: “It happened because somebody was using pistachio shells as soil amendments in the blueberry field,” says Taylor. “Well, who knows about that?”

As you move up the chain, other issues present themselves. What was in the railcar before your shipment? Did the truck driver who dropped off potatoes today properly clean his truck after hauling peanuts yesterday? To help guard against this type of cross-contamination, suppliers need to be aware of what your allergen control requirements are, says Massong.

“If the manufacturer can’t get that guarantee from their supplier, they need to do testing themselves to make sure the incoming ingredient is free from that particular allergen,” he says. “If you can’t start clean, how can you stay clean?”

Suppliers need to be willing to offer documentation that materials are allergen free, and a notification process should be in place for them to alert you of any changes in allergen status at any point. Regular audits can help ensure your suppliers have an effective allergen control plan in place. In addition to an allergen control plan, they should also have cleaning procedures in place.

Once the product comes in the door, the first step is verifying the labeling on the materials against what is actually in the box. After that is done—or as part of that process—the next step is ensuring the integrity of the packaging. It’s OK to get multiple kinds of products, even allergens, in the same shipment—as long as the packaging is secure.

“If we’re receiving peanut pieces, we don’t want peanuts to be all over the outsides of the packaging,” says Clifford. “We would reject the truck, because we don’t want to run the risk of having pieces being uncontrolled within our warehouses.”

When materials are accepted, they should be labeled with what allergens they contain, either by color coding or another easily identifiable tag. After that, the materials need to be stored. When you get to this stage of the allergen control plan, you should isolate allergens within the warehouse and identify which areas you want to contain which allergens, says Gerry Gray, director of product management for Plex Software.

“We keep our peanut products in one area,” says Gray, from a processor's perspective. “We keep our egg-based products in another area, we keep our seafood products in a third area, so that there are no cross-contamination opportunities in the storage of those materials.”

If it’s not possible to have entirely separate storage areas, then keeping allergens and non-allergens separated within a storage space or storing similar allergens together are other options. A documented response plan to a spill within storage areas is important as well.

Recipe and material management

When it comes to recipe management, there are a couple different things to keep in mind. The first is the actual recipes themselves. If you’re making peanut butter, obviously there are going to be peanuts involved.

“By identifying what you want it to contain, you’re also identifying what you don’t want it to contain,” says Gray.

The second aspect is using the recipes and their requirements to set up which production lines will be producing the products, how they will be managed and how materials will be delivered.

Gray offers the example of a production line that produces three products: one with eggs; one with eggs and seafood; and one with eggs and peanuts. In this case, you could run the eggs products first and then run the eggs and seafood products immediately after without worrying about cross-contamination. But, you would have to clean the production line between the eggs/seafood and eggs/peanut products, because otherwise you would run the risk of seafood contaminating the last product.

Gray also offers this rule of thumb for scheduling the order of products on a line: “I always like to say ‘leave the peanuts to last,’ because those darn things can hurt people worst of all.”

As production begins, materials are called for, often electronically, then delivered from storage areas. This offers another area for cross-contamination, not only with the ingredients themselves, but other production lines that may be intended for the production of allergen-free products.

At Nestlé, hygienic zoning is used to specify where allergens can be stored, where they can be staged and even the paths employees can use to deliver ingredients to the lines as production calls for them.

“You want to minimize movement of certain things through the facility as much as possible,” says Clifford. But, he also points out that the direct route isn’t always the best because of the possible contamination concerns of moving allergens through certain areas of the facility. So, keep that in mind when setting up the routing for the delivery of ingredients.

One final area of concern with recipes is managing them as they’re changed. A new recipe clearly would require new plans for managing its ingredients and potential allergens, but changes to existing recipes can have the same effect. As part of its overall management of change program, Nestlé has procedures in place for something that would seem to be a small change in a recipe, but can have a big effect on operations.

“There’s a difference in how you handle, say, peanut butter and peanut pieces in terms of how you clean and what you’re worried about,” says Clifford. “So, something as simple as that might cause us to make some substantial changes in how we’re cleaning, how we’re managing materials, how we’re managing production scheduling—everything would be fair game for evaluating changing in order to maintain the food safety integrity and the quality integrity of the product.”

At a company the size of Nestlé, the ability to be flexible helps in this regard. With multiple production locations, changes can be evaluated to see if they should be shared across all plants that make a certain product or contained in only a portion of those locations. In a smaller operation, you may not have a choice as to where a particular product needs to be made, but having a process in place for managing changes to a recipe or ingredients can help avoid problems. But, in a company with as many production facilities as Nestlé, a change could create enough problems at the production level that the decision would be made not to implement it.

Hygiene and cleaning

Overall hygiene and cleaning efforts to prevent allergen contamination are different from a lot of other concerns. While a plan is required to deal with all potential contaminants, the possibility of cross-contamination from something as simple as a damaged box being accepted in receiving makes allergen control a little trickier. And, with other contaminants, there should be steps built into the process to combat them, says FARRP’s Taylor.

“Unlike bacteria pathogens, you don’t have kill steps, so you have to be vigilant from beginning to end,” he says.

Cleaning is a big part of that vigilance, and it starts well before the buckets and mops come out. A good design for plants and equipment that allows easy access for cleaning and sanitizing and avoids “dead spots” such as hollow rollers can save a lot of headaches later. Dead spots can allow food or ingredients to accumulate, opening up the possibility of contamination.

“Unlike bacteria pathogens, you don’t have kill steps, so you have to be vigilant from beginning to end.”

– Steve Taylor

Once you move into the actual cleaning process, detailed cleaning plans and clearly defined responsibilities are crucial, especially if you have an outside contractor that handles facility cleaning while production or in-house cleaning workers are responsible for clean in place (CIP) or other production cleaning protocols.

Being able to track compliance with cleaning procedures is important as well. First, it allows you to have a better sense of any changes you may need to make to cleaning to ensure it is being done efficiently and correctly without interfering with production. Second, it provides another check for compliance with allergen control procedures, because by testing and tracking cleaning results, you can find where food or ingredients may be accumulating without the areas being properly cleaned.

The bottom line

As with any area of operations, allergen control comes at a cost, and it becomes more expensive as you add more products that include allergens. But it’s still cheaper than a recall—and a lot less damaging to your reputation.

Balance is the key. It’s possible to design an allergen control plan that uses the very best, most extensive methods on the market, but will doing so allow you to keep the lights on?

“Any system can be devised to reduce the risk to very, very low limits, but there’s a cost,” says Massong. “That’s the part that is challenging for most manufacturers.”

The good news is that even simple steps can go a long way toward reducing your risk of an allergen-related issue. By developing a plan, regularly monitoring its effectiveness and making changes when needed, processors can help limit their chances of a costly, brand-damaging recall due to allergen contamination.

For more information:

Gerry Gray, Plex Software, 888-454-7539,

ggray@plex.com, www.plex.com

Frank Massong, Allergen Control Group Inc., 866-817-0952 ext. 224,

frank.massong@glutenfreecert.com, www.glutenfreecert.com

Steve Taylor, PhD, FARRP, 402-472-2833,

staylor2@unl.edu, farrp.unl.edu

This article was originally posted on www.foodengineeringmag.com.

.webp?t=1721343192)