PFAS Litigation and FDA Updates for the Food Industry

Managing PFAS litigation risk requires food manufacturers and suppliers to take adequate steps to assess their exposure and allocate responsibility

No chemical compound has presented the scale of exposure and potential industry-wide liability risk as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS have been ubiquitous since the 1940s, and nearly all major industries have PFAS concerns in one way or another. The sheer scale of the issue is yet to be quantified; an increase in state and federal regulatory requirements and enforcement, as well as lawsuits concerning PFAS, are a near certainty.

Federal agency actions concerning PFAS have been relatively slow to develop in comparison to the actions already taken by some states. This is understandable, because there are thousands of compounds that meet the definition of PFAS1 and no consensus on whether and how to make individualized determinations on which of these substances present a risk to health and safety. In evaluating at what level these compounds present a risk to the health of humans and animals, the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are focusing on three issues: bioaccumulation, persistence, and toxicity.

FDA Action

Concerning the food manufacturing industry, FDA has taken few enforcement actions other than two reported recalls of food with PFAS. Both recalls were in July 2022 and concerned seafood. While recalls are generally "voluntary," the public notices are approved, if not dictated, by FDA. The identical notice for both recalls stated:

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a diverse group of human-made chemicals used in a wide range of consumer and industrial products. PFAS do not easily break down, and some types have been shown to accumulate in the environment and in our bodies. Available studies suggest associations between PFAS exposure and several health outcomes including but not limited to increased cholesterol levels, increases in high blood pressure and pre-eclampsia in pregnant women, developmental effects, decreases in immune response, change in liver function, and increases in certain types of cancer.2

FDA has taken steps to develop regulations to address PFAS in the food manufacturing industry. In November 2016, the industry agreed with FDA to withdraw regulations authorizing the use of some "long-chain" PFAS compounds, although some PFAS are still permitted in cookware, processing aids, and packaging.3 In 2020, manufacturers of food contact substances containing "short-chain" PFAS committed to a three-year market phase-out, which FDA continues to oversee.4

On August 5, 2021, FDA published a "Dear Industry Letter" referencing scientific and medical research on the adverse health effects of PFAS.5 FDA also published a survey in February 2022 finding that 97 percent of food samples had no detectable levels of PFAS and concluding that there is no cause for avoiding foods.6 In further support of its conclusion, FDA advises that since 2019, a total of only ten samples from seafood had detectable PFAS levels.6 FDA and CPSC have also issued Requests for Information to identify the products PFAS are used in and the health impacts from exposure.7 FDA continues to study the effects of PFAS in the general food supply8 and in other consumer products.9 As regulatory efforts continue to accelerate, companies should closely monitor FDA's public dockets and announcements regarding PFAS.

Current PFAS Litigation and the Food Industry

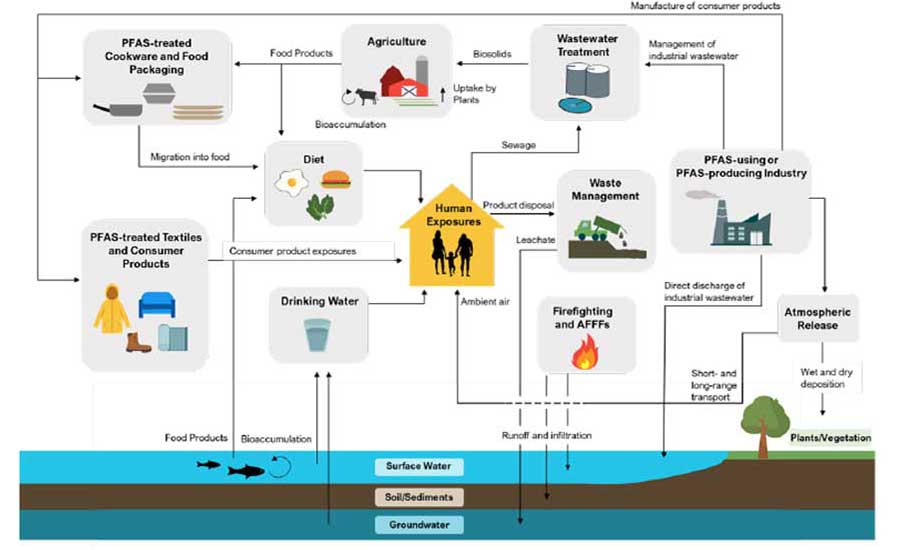

Until recently, the major controversies surrounding PFAS liabilities focused on groundwater and drinking water utilities, as well as exposure at military facilities and airports related to the use and run-off from firefighting foam. Today, downstream users, including food and beverage producers, are dragged into the fray as plaintiffs' lawyers work to get a foothold in large-scale, nationwide litigation (Figure 1).

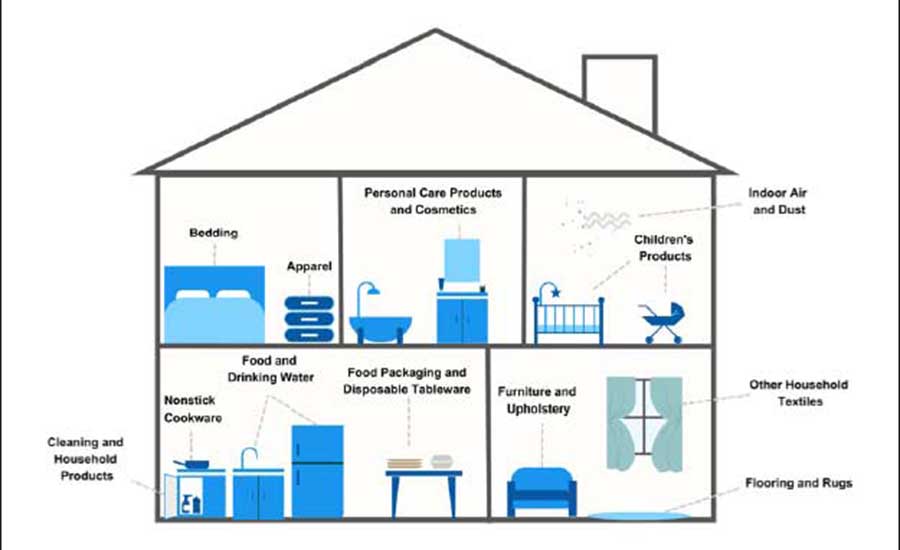

Consumer fraud class actions involving FDA-regulated food products, cosmetics, and consumer products are proliferating. Claims often relate to package labeling stating that the product is "natural" or contains "100 percent" of a certain ingredient (e.g., fruit juice) where detectable quantities of PFAS were allegedly discovered. These consumer product cases encompass a large range of health-conscious products, including cosmetics,10 food packaging,11 food and beverages,12 animal food,13 and other consumer products.14

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Of the recently filed PFAS-related consumer fraud cases, at least five involve fruit juices and similar beverages advertised as "all-natural," "organic," or similar language. Each case has been filed by the same group of plaintiff's attorneys and asserts near-identical claims for breach of express warranty, fraud, constructive fraud, unjust enrichment, and related state law claims. Plaintiffs generally emphasize that the product contains PFAS in excess of EPA's lifetime drinking water advisories and claim that they would not have purchased that product if they had known about the PFAS contamination.15

The good news for the food industry in a potential large-scale litigation—downstream defendants present a uniquely complex evidentiary challenge for any plaintiff to identify the proper party, marshal evidence to establish liability, prove causation,16 and allocate damages. Dismissing such a class action, the Sixth Circuit stated, "Seldom is so ambitious a case filed on so slight a basis," and found that the proposed class lacked standing to proceed.

While few courts have had an opportunity to offer guidance on the merits of these claims, several cases have been voluntarily dismissed following apparent settlements or because of bankruptcies,17 but others have been dismissed on the merits or remain pending. For example, the Northern District of Illinois issued an opinion dismissing two related cases, Richburg v. Conagra Brands, Inc. and Ruiz v. Conagra Brands, Inc., which alleged fraud, unfair and deceptive trade practices, and false advertising concerning Orville Redenbacher and Angie's BOOMCHICKAPOP microwave popcorn. The court’s opinion relied on FDA's Authorized Uses of PFAS in Food Contact Applications, which expressly authorizes the use of PFAS in microwave popcorn bags.18 The court found that the plaintiffs failed to allege concrete injuries and that, in light of FDA's exemption of migratory substances from the mandated list of "ingredients," PFAS could not be considered an "ingredient" of the popcorn such that the reasonable consumer would be misled by its exclusion from the product's ingredient list.

In Hamman v. Cava Group, the Southern District of California denied the plaintiff's common law claims for fraudulent omission, finding that the defendant had no duty to disclose the presence of PFAS in its products. However, the court found that the plaintiff had successfully demonstrated economic injuries on the theory that the plaintiff would not have purchased Cava's products had he known of the presence of PFAS in its packaging. Furthermore, the court ruled that the plaintiff should be permitted to bring claims under California's consumer protection statutes, as he had advanced an actionable theory on why the products are unsafe and why the labels are misleading. On December 4, 2023, the court denied Cava Group's motion to dismiss plaintiff’s claims for punitive damages, breach of implied warranty, and unjust enrichment.

In several cases, courts have dismissed plaintiffs' claims regarding PFAS contamination in consumer products for failure to sufficiently plead injury-in-fact. However, these dismissals have been without prejudice, allowing plaintiffs to file corrective pleadings.19 In Esquibel v. Colgate-Palmolive, Inc., the Southern District of New York found that the plaintiffs' complaint did not "plead facts sufficient to support a plausible inference that the bottles [of mouthwash] Plaintiffs purchased were tainted" because the plaintiffs based their allegations solely on third-party testing without "alleg[ing] that bottles they actually purchased were tested,… how many units… were tested, where those units were acquired, where the test took place, or what entity performed the test." The court found that these sparse allegations could not demonstrate that the presence of PFAS in bottles that plaintiffs purchased was anything more than a "sheer possibility." Nevertheless, plaintiffs were granted leave to file an amended complaint—perhaps more detailed factual allegations will satisfy the injury-in-fact requirement. These cases bear close monitoring and could impact future lawsuits.

Looking Forward

For the food industry, managing PFAS litigation risk requires manufacturers and suppliers to take adequate steps to assess their exposure and allocate responsibility (Figure 2). While the labeling phrase "no intentionally added PFAS," will satisfy many state regulatory requirements, it begs the question: How much PFAS is in the product, and why? Current litigation focused on PFAS false advertising, consumer protection violations, and deceptive statements made in marketing and environmental, social, and governance ("ESG") reports serve as test cases for the plaintiffs' bar for future litigation nationwide. Furthermore, as regulation and scientific and medical literature continue to grow, product liability lawsuits are likely to emerge seeking damages for personal injury.

Companies do not like to hear from their lawyers that they have good defenses; they like to hear that they will not become embroiled in multi-year mass litigation in the first place. If prior litigation has taught us anything, it is the need for early attention to reduce risk and minimize potential exposure. No prior litigation has presented the scale of exposure and potential industry-wide liability risk that PFAS presents. While many individual downstream processors, distributors, and users are taking steps to mitigate risk, sitting idle does not guarantee litigation will not hit you, and "lying behind the log"—a common defensive litigation strategy—is effective unless and until you become the log! In the interim, taking a few proactive steps will provide peace of mind.

References

- Hammel, E., et al. "Implications of PFAS definitions using fluorinated pharmaceuticals." ISCIENCE. March 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8933701/.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Bumble Bee Foods, LLC Issues Voluntary Recall on 3.75 Oz Smoked Clams Due to the Presence of Detectable Levels of PFAS Chemicals." July 6, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/bumble-bee-foods-llc-issues-voluntary-recall-375-oz-smoked-clams-due-presence-detectable-levels-pfas; and FDA. "Crown Prince, Inc. Issues Voluntary Recall of Smoked Baby Clams in Olive Oil Due to the Presence of Detectable Levels of PFAS Chemicals." July 15, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/crown-prince-inc-issues-voluntary-recall-smoked-baby-clams-olive-oil-due-presence-detectable-levels.

- FDA. "Market Phase-Out and Revocation of Authorization of Long-Chain PFAS, Authorized Uses of FPAS in Food Contact Applications." May 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/process-contaminants-food/authorized-uses-pfas-food-contact-applications.

- FDA. "Market Phase-Out of Certain Short-Chain PFAS, Authorized Uses of PFAS in Food Contact Applications." May 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/process-contaminants-food/authorized-uses-pfas-food-contact-applications.

- FDA. "Letter to Manufacturers and Distributors of Fluorinated Polyethylene Food Contact Containers." August 5, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/151326/download.

- FDA. "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)." May 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/chemical-contaminants-food/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas.

- "Fluorinated Polyethylene Containers for Food Contact Use; Request for Information." Federal Register. 87 FR 43274. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/07/20/2022-15455/fluorinated-polyethylene-containers-for-food-contact-use-request-for-information.

- FDA. "FDA Update on PFAS Activities." May 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-update-pfas-activities.

- 117th Congress. "Modernization of Cosmetics Act of 2022." PL 117-328, §3506, 136 Stat 4459, 5860 (2022). https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr2617/BILLS-117hr2617enr.pdf.

- Hicks v. L'Oréal U.S.A. Inc. (S.D.N.Y. September 30, 2023); Solis v. Coty, Inc. (S.D. Cal March 7, 2023); Onaka v. Shiseido Americas Corp. (S.D.N.Y March 28, 2023); Brown v. Coty, Inc. (S.D.N.Y. March 29, 2023).

- Clark et al v. McDonald's Corporation (S.D. Ill. March 28, 2022); McDowell v. McDonald's Corporation (N.D. Ill. March 31, 2022); Little v. NatureStar (E.D. Cal. April 8, 2022); Azman Hussain v. Burger King (N.D. Cal. April 11, 2022); Hamman v. Cava Group (S.D. Cal. April 27, 2022); Richburg v. Conagra Brands (N.D. Ill. May 6, 2022); Ruiz v. Conagra Brands (N.D. Ill. May 6, 2022); Azman Hussain v. Burger King (N.D. Cal. April 11, 2022).

- Alanna Morton v. Health-Ade LLC (S.D.N.Y January 9, 2024); Barnes v. KOS, Inc. (S.D.N.Y. November 16, 2023); Bedson v. Biosteel (E.D.N.Y. January 27, 2023); Lurenz v. The Coca-Cola Company (S.D.N.Y. December 28, 2022); Lurenz v. The Coca-Cola Company (E.D.N.Y. February 22, 2023); Toribio v. Kraft Heinz (N.D. Ill. November 29, 2022).

- Humphrey v. J.M. Smucker Co. (N.D. Cal. November 4, 2022); Kueck vs. Nestlé Purina PetCare Co. (N.D. Cal. November 17, 2023).

- Dalewitz v. Procter & Gamble Company (S.D.N.Y. September 22, 2023); Esquibel v. Colgate-Palmolive Co. (S.D.N.Y. November 9, 2023); Bounthon v. The Procter & Gamble Company (N.D. Cal. February 21, 2023); Brigette Lowe et al. v. Edgewell Personal Care Company (N.D. Cal. January 12, 2024).

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). "Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFAS: Fact Sheet for Communities." June 2022. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-06/drinking-water-ha-pfas-factsheet-communities.pdf.

- Hardwick v. 3M Company, et al., 2023 WL 8183812 (6th Cir. November 27, 2023).

- Smith v. Wm. Bolthouse Farms, Inc. (E.D.N.Y. January 19, 2023) (voluntarily dismissed February 22, 2023); Bedson v. BioSteel Sports Nutrition Inc. (E.D.N.Y. January 27, 2023) (voluntarily dismissed December 26, 2023); Clark, et al v. McDonald's Corporation (S.D. Ill. March 28, 2022) (voluntarily dismissed Jan. 8, 2024); McDowell v. McDonald's Corporation (N.D. Ill. March 31, 2022) (consolidated with Collora v. McDonald's Corporation) (voluntarily dismissed January 8, 2024).

- FDA. "Authorized Uses of PFAS in Food Contact Applications." May 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/process-contaminants-food/authorized-uses-pfas-food-contact-applications.

- Hernandez v. the Wonderful Company, LLC (S.D.N.Y. February 14, 2023); Hicks v. L'Oréal U.S.A. Inc. (S.D.N.Y September 30, 2023); Solis v. Coty, Inc. (S.D. Cal March 7, 2023); Onaka v. Shiseido Americas Corp. (S.D.N.Y March 28, 2023); Esquibel v. Colgate-Palmolive Co. (S.D.N.Y. November 9, 2023).

Michael A. Walsh, J.D., is Senior Counsel at Clark Hill PLC.

Emma C. Jenevein, J.D., is an Associate at Clark Hill PLC.

Christopher B. Clare, J.D. is a Senior Attorney at Clark Hill PLC.