Ten Years Later: Defining Food Fraud and Envisioning the Future

A look at how far we’ve come and where we’ve yet to go

Ten years after our publication that first defined food fraud in an academic sense,1 there has been a lot of progress, but we still have a long way to go. Management systems are maturing and shifting the resource-allocation decision-making from tactical to strategic.2 More formal management systems help identify the most efficient countermeasure or control system, leading to clear direction on the optimal action and how much is enough. The next wave will be more formal management systems and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). These methods will become obvious supply chain management best practices.

Background

April 30, 2021, was the 10-year anniversary of the publication of our “Background on Defining the Public Health Threat of Food Fraud.”1 This work was funded by a U.S. Department of Homeland Security grant through the National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD, now the Food Protection and Defense Institute) at the University of Minnesota. This publication defined and presented the scope of food fraud. To be clear, we did not create the term (or the problem!); we were just the first to publish research on the definition.

On a personal note, the NCFPD grant was a key career milestone for me since only one month into my first full-time assistant professor faculty position, this grant-funded my entire appointment. I had just made the very unusual move from my research home in the School of Packaging in the College of Agriculture to join the School of Criminal Justice faculty in the College of Social Science. This was a bit of a risky commitment by Michigan State University since I had an appointment that required me to eventually cover the cost of my salary, benefits, and all costs.

Since then, this has been the most-cited definition of food fraud. It is interesting to note that although the scope of the types of food fraud has adjusted or adapted, the core definition was broad enough and thorough enough to stand the test of time:

Food fraud is an intentional act for economic gain, whereas a food safety incident is an unintentional act with unintentional harm, and a food defense incident is an intentional act with intentional harm.

The expanded definition statement still includes nuanced and relevant points such as the broad scope including packaging and a more comprehensive list of fraud types, including smuggling and theft:

Food fraud is a collective term used to encompass the deliberate and intentional substitution, addition, tampering, or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients, or food packaging; or false or misleading statements made about a product, for economic gain. Food fraud is a broader term than either the economically motivated adulteration (EMA) defined by the [U.S.] Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the more specific general concept of food counterfeiting. Food fraud may not include “adulteration” or “misbranding,” as defined in the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) when it involves acts such as tax avoidance and smuggling.1

Doing a review research project is essential, but the real value comes when considering the practical applications.

Figure 1: Food Risk Matrix

Practical Applications

Our “Practical Application” statement did hold true. There was increased awareness of food fraud as a problem and an area that needed to be managed. Also, food fraud did develop unique terminology and methods that are different from—but connected to—food quality, food safety, and food defense.

As economically motivated adulteration [awareness and threat] grows in scope, scale, and awareness, it is conceivable that food fraud will achieve the same status as an autonomous concept, between food safety and food defense. This research establishes a starting point for defining food fraud and identifying the public health risks.1

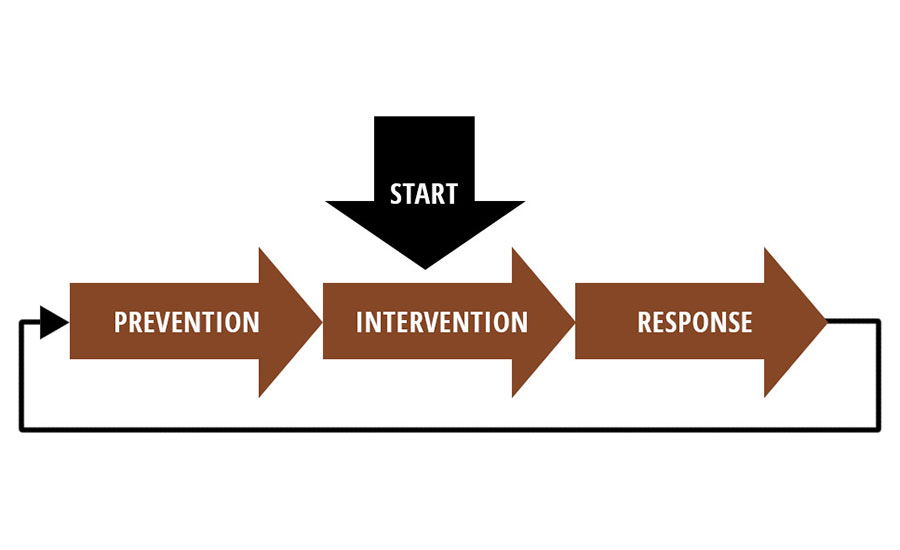

Figure 2: Food Fraud Risk Response

This article not only covered definitions and scope but also laid out the foundation to connect with the other types of food risks (the food risk matrix, Figure 1), risk response (how to start the prevention, intervention, and response cycle, Figure 2), and the proactive response (food fraud prevention and criminology, Figure 3).

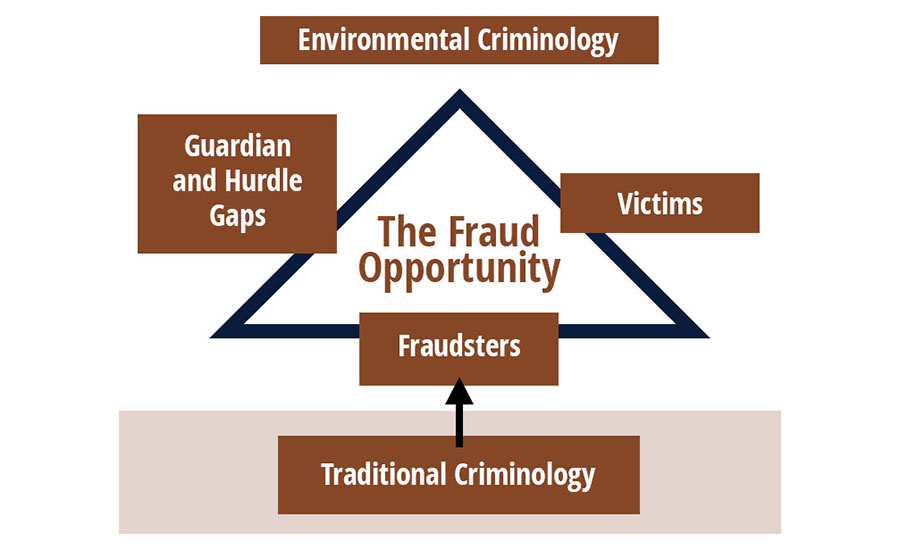

We introduced novel criminology concepts to apply crime prevention, shifting from risks to vulnerabilities. The focus of crime prevention on reducing system weaknesses was a crucial shift in mindset. This was a seed for several new research projects that expanded the terms, definitions, and methods.

Now let’s review the steps from the definition to the common requirements for food fraud prevention and the Vulnerability Assessment and Critical Control Points plan (VACCP).

Figure 3: Proactive Response to Food Fraud

Evolution of VACCP

Initially, food fraud was not defined as a “thing”—a separate and specific concept—so it was not directly addressed by anyone. At that time, a crime that occurred for economic gain using food was addressed as a food safety incident, a food quality incident, or some type of crime that was forwarded to a company’s corporate security group or a law enforcement agency. Since the known food safety countermeasures didn’t apply, any further root-cause investigation or prevention responses weren’t conducted.

When using laws and regulations from food safety, labeling, or customs, food fraud incidents such as Sudan red, melamine, or horse meat were usually defined as either a food safety incident or an odd mislabeling problem. Again, food fraud wasn’t a thing, so the issues couldn’t be adequately categorized. Without adequate categorization, there were inefficient prevention, intervention, and response. After melamine adulteration, and then during the horse meat scandal, there was a growing awareness that food fraud was a thing—a unique phenomenon that required a fundamentally different approach than for other food risks.

To facilitate the shift toward prevention, it is important to understand that the root cause of food fraud has fundamentally different properties than food safety's traditional bad bugs, bad chemicals, and physical hazards. Reducing food fraud opportunities requires a deeper understanding of the public health risk in order to consider the specific types of food fraud risks.1

Crime prevention and supply chain management theories existed, but they had not been applied to this specific problem. There was no common method, refined best practices, or requirement to act—until the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) took notice. In July 2012, the GFSI Board of Directors created their Food Fraud Think Tank to address the question of “what is food fraud” and then “what could be done about it” before considering “what is the role of GFSI in food fraud prevention?” The GFSI Food Fraud Think Tank constantly said, “We need to shift from the ‘what’ to the ‘how.’” To note, I was one of four people in the first group that expanded to six.

In the midst of that project, the horse meat incident occurred, which increased the intensity of the focus. GFSI published their Food Fraud Position Paper in December 2014.3 This paper stated that food fraud management would become a requirement in the following GFSI Benchmarking Document. The Benchmarking Document Version 8 was published in February 2017 and noted the required implementation in January 2018. Food fraud was now a requirement—it was not optional—for a food safety management system.

There is an essential step of reinforcing the action when studying the adoption of new norms, methods, standards, or certifications. Sometimes—often—a new requirement does not get fully adopted. The effort gets difficult, there are other urgent distractions, and projects die. GFSI proactively avoided this lull by quickly publishing the May 2018 Food Fraud Technical Document.4 Published five months after the required implementation, this did not provide any new information but helped refine the explanation of the requirements. Most importantly, the document was a clear and firm statement that food fraud management was necessary, it was required, and it wasn’t going to fade away.

One of the most important outcomes of these activities was explaining how food fraud assessment and management fit under the umbrella of a food safety management system. GFSI explicitly required, separate from the food safety/Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plan, a food fraud, and another food defense, assessment. The food safety issues were “hazards” in the HACCP plan. Continuing the HACCP concept, the food defense issues were defined by GFSI as “threats,” and Threat Assessment and Critical Control Points (TACCP) and food fraud issues were vulnerabilities and VACCP. The result was an easy-to-identify and -remember set of activities in HACCP, TACCP, and VACCP.

Management Systems

We don’t start by preventing everything, and we also don’t start with formal management systems for every process. The formalized and standardized systems develop on their own until we realize that there should be more coordination. Food fraud prevention is at this stage.

It is a natural evolution for more formalized systems to be developed and implemented, and we realize the value. As quality management cycled through different philosophies, some actions kept improving the activities for each project. Suddenly, some company separated itself from the pack, and all the lagging competitors tried to add similar systems quickly.

Fortunately, the science of food fraud prevention is leveraging all the lessons learned to grow on a simple and more thorough foundation. The GFSI food fraud requirements were the keystone that put this in motion and were based on sound fundamental concepts from food science, criminology, and managerial accounting/enterprise risk management (ERM). The requirement in a food safety standard and certification created a common starting point that was not optional. In many (most?) other industries, addressing product fraud prevention never gained this level of momentum since the scope was often too broad, and there was no standardized requirement.

The food fraud prevention standards and certifications themselves leveraged widely adopted standards by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)—love them or hate them, they are internationally recognized, consensus-based, formal standards:

- ISO Management Systems Standards: There is a common method for managing many different organizational activities to meet its objectives efficiently. ISO provides a standardized way to organize the concepts, improving communication and enabling sharing of best practices.

- ISO 9000 Quality Management: A set of common practices for all industries to improve the consistency of products and services. This also set out the direction for a management system and decision-making.

- ISO 31000 Risk Management: This defined common terms and methods. A key is a concept of “likelihood and consequence,” not “probability and severity.”

- ISO 22000:2018 Food Safety Management: This is the foundation for the GFSI food safety management system. In 2018, “food fraud” was mentioned, and thus, now, without debate, is not optional for ISO 22000 certification.

- ISO 12931: Performance Criteria for Authentication Solutions: These criteria for authentication solutions used to combat counterfeiting of material goods led to the identification of related standards that apply. These include a definition of product fraud, which emphasizes the efficiency of focusing on vulnerabilities and the importance of building on a criminology foundation. I was the founding chair of the ISO Technical Committee 247 that started the development of this standard.

Food Fraud Management Systems

Starting with the clarity from ISO standards and academic theories and building on actual project successes and failures, there are more formal or directly applicable food fraud methods and procedures. Social scientists would call this the “action-research paradigm,” which is research and application working on problems together. Often, researchers observe activities and then comment on how things could or should improve.

Our initial article1 was highly collaborative during the development. Our following research project evolved with practitioners as we saw an unmet need or unsolved problems. We’ve had over 40 coauthors and research collaborators from more than 10 countries, from government and associations, and their work often came directly from marketplace projects.

Supply Chain Management: The New Home

Over time, food fraud prevention research followed an evolution from simply what the problem is to how to manage proactive prevention management. The evolution of the key “science and sciences” of food fraud prevention are the following:5

- Identifying the public health problem (food authenticity and food science)

- Removing the product from the supply chain (food safety systems)

- Understanding the root cause (criminology, routine-activities theory)

- Examining why criminals attacked (social science, rational-choice theory)

- Understanding the root cause based on system weaknesses (situational crime prevention)

- Addressing how the problem is, or could, be handled (public policy and standards)

- Conducting resource-allocation decision-making (managerial accounting, ERM)

- Coordinating the implementation across a system (supply chain management, quality management)

Next is for the standardized, common practices to become routine, well-known, and just part of competent business management. Remember, early on, quality management had many fits and starts before it matured from a specialty operations activity to inhering in all well-functioning organizations. Personally, I remember my first years working at Chevron Corporation when we went through Deming, Crosby, Quality Function Deployment, and then later Six Sigma. I still frequently refer to Deming’s philosophy of “Plan-Do-Check-Act”—and it is a section header in ISO 22000.

Remember also that initially, quality management was perceived as a trend that would fade away. Early on, food safety and HACCP were applied only in extremely specific situations. Now, no company of any kind would argue that quality management was a waste of time.

The current state appears to be that food fraud prevention strategies are becoming simplified, more commonly understood, and more widely implemented. For example, VACCP is a common description to define training, education, and guidance. As the basic activities become more well-known, they become SOPs with the formal structure of the standards and certifications. These are not only becoming just best practices but also are commonly understood as simply “what you need to do.” As more VACCP plans are implemented, refined, and shared, there will be a more widespread realization that management systems are logical.

Stall from COVID-19

Obviously, COVID-19 significantly disrupted everything in the world. Implementing management systems and nonemergency process improvement projects had to be put on hold. Many projects and training activities were idled starting around March 2019. We are just now seeing industry and regulators begin to get back to normal. That return to normalcy leads to the restart of many projects, such as more thorough food fraud prevention strategies.

If anything, the retailers and food manufacturers are restarting their longer-term food safety strategic project that includes their management and confirms their suppliers are compliant (and fully compliant). Food fraud prevention is one of those focus areas.

Conclusions

The 10 years since defining food fraud to now have been both a blur and like treading water. It took 10 years to get from the first scholarly definition of the term1 to inclusion in standards and certifications (GFSI in 2017 and ISO 22000 in 2018), and then the more in-depth research and foundations.6 Then, just as the food fraud prevention project and activities were starting to accelerate, there was a pause from COVID-19. Today, there is a sense of a return to business activities that includes process improvement.

To restart your food fraud prevention strategy—and prepare for the inevitable questions from your customers—here are several recommendations:

- Conduct a gap analysis: This is important to review your current state and what/if you need to do anything. This will help explain exactly where you need to act—or defend just continuing with your current plan.7

- Train to build a foundation and then study the key concepts: The gap analysis will identify your strengths and weaknesses. There are many resources for capacity and capability building. Capacity building is training and educating more team members; capability building is increasing the team's expertise.8

- Update your food fraud prevention activities: This should include (1) updating your food fraud vulnerability assessment and your food fraud prevention strategy. This may include a new task force or project to define and create a resource-allocation proposal. The update also includes refining your countermeasures and control systems (including food authenticity tests, methods, sampling plans, and data management).9

While the underlying theories can be complex, and there are ranges of disciplines applied to the research, the food fraud prevention starting point is simple. Fortunately, some methods and procedures have been refined and streamlined. The last 10 years brought us to this solid and harmonized point. The next 10 years will advance us to SOPs and management to efficiently and effectively reduce the opportunity for fraud and protect the food supply chain.

References

- Spink, J. and D.C. Moyer. 2011. “Defining the Public Health Threat of Food Fraud.” J Food Sci 76(9): R157–163.

- www.food-safety.com/articles/6563-reducing-the-risk-of-fraud-in-the-spice-industry.

- mygfsi.com/press_releases/gfsi-position-paper-on-mitigating-the-public-health-risk-of-food-fraud/.

- mygfsi.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Food-Fraud-GFSI-Technical-Document.pdf.

- Spink, John, Integrated Supply Chain Management (Okemos, MI: York Partners LLC, 2020).

- Spink, J., et al. 2019. “Introducing the Food Fraud Prevention Cycle (FFPC): A Dynamic Information Management and Strategic Roadmap.” Food Control 105: 233–241.

- www.foodfraudpreventionthinktank.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FFPTTPrimer-FF-Compliance-v2a.pdf.

- www.foodfraudpreventionthinktank.com/food-fraud-prevention-academy/.

- www.foodfraudpreventionthinktank.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FFPTTPrimer-FF-Prev-Method-v2.pdf.

John Spink, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Supply Chain Management in the Eli Broad College of Business at Michigan State University.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →