Food quality plans help meet demand, maintain quality certifications

Consistent, repeatable steps to ensure food quality help processors maintain their brands’ good names.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

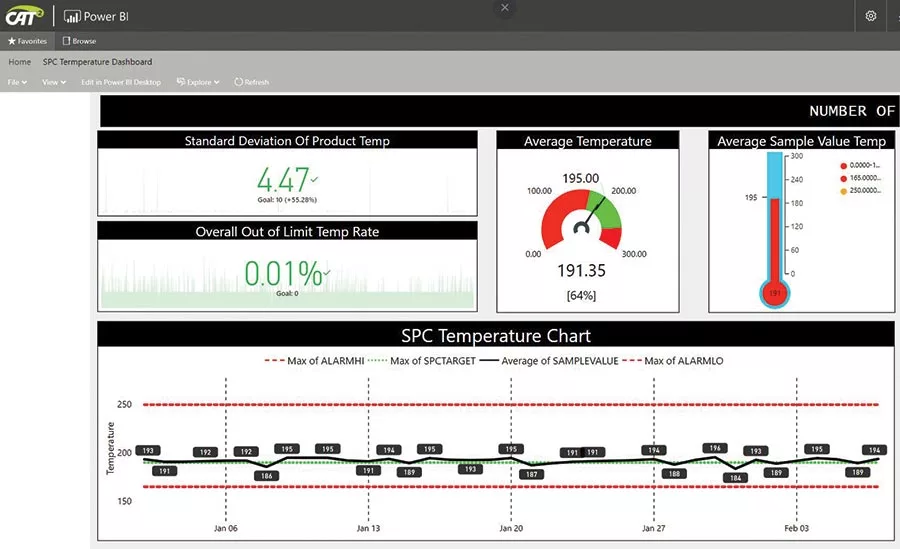

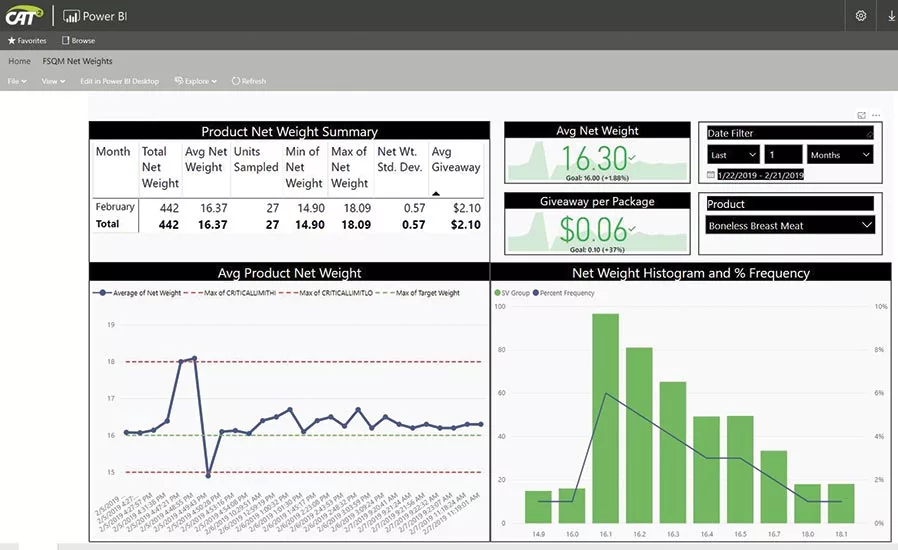

These SPC charts are monitoring temperature and weights. Users on a production line monitor this data in real time to see if a process is trending out of control so that they can perform corrective actions to minimize loss and prevent nonconformance.

Charts courtesy of CAT Squared

These SPC charts are monitoring temperature and weights. Users on a production line monitor this data in real time to see if a process is trending out of control so that they can perform corrective actions to minimize loss and prevent nonconformance.

Charts courtesy of CAT Squared

Consumers expect their food to be safe, and there are methodologies like HACCP, FSMA, FSIS, etc., to ensure that it is. If there is a possibility of a food contaminant, that product will be recalled to ensure the health and well-being of consumers. Quality is a bit of a different story. But it’s just as important when it comes to consumer expectations.

Scott C. Lane, CFS, food safety trainer/food safety and quality plan consultant at Eagle Tower Inc., explains it this way: “If a product fully complies with FDA or USDA regulations, and there are no food safety hazards, but the overall quality of an established product declines, so will its customer demand. When it comes to food quality, a brand name or company’s reputation can quickly become tarnished, or worse, become valueless [if quality declines].”

“When it comes to food quality, a brand name or company’s reputation can quickly become tarnished, or worse, become valueless.”

— Scott Lane, CFS, food safety

trainer/food safety and

quality plan consultant at

Eagle Tower Inc.

If the quality of a product or ingredient is known—or has usually been known—to be a reliably high, then anything else will be perceived to be inferior, he says. For instance, he says to imagine that your favorite chocolate bar was always made with high quality chocolate and cocoa butter that melted in your mouth. Now suppose that same chocolate bar is being made with cheap chocolate mixed with some carob powder, and the cocoa butter was replaced with coconut or palm oil.

“The quality of the chocolate bar and taste would be totally different; it would be like night and day,” Lane says. “Not only did the food quality of the product change, but your recollection of the quality of the brand has now changed, and not for the good.”

Like HACCP for a food safety plan, a food quality plan follows similar methodologies to help ensure that food processors are meeting their own companies’ quality specifications, as well as their customers’ expectations.

A food safety plan “defines a program of controls to reduce the risk of quality threats or nonconformances, the methods and responsibilities of those control measures, proper documentation, and what corrective actions should be implemented if nonconformance occurs,” says Jack Teague, implementation specialist, CAT Squared.

“Food quality

addresses both the

consistent production process

and consistent supply chain quality to ensure consistent finished good quality.”

— Dan Creinin,

key account executive

at Elemica

Dan Creinin, key account executive at Elemica, a digital supply network company, says that consumers want to know that what they buy is going to taste the same whenever they buy it.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

“Food quality addresses both the consistent production process and consistent supply chain quality to ensure consistent finished good quality,” he says.

Lane adds that a food quality plan is similar to a HACCP plan; however, instead of there being control points (CPs) and critical control points (CCPs), representing the identified food safety-related controls, there are quality points (QPs) and critical quality points (CQPs) representing the identified quality-related controls.

Carey Allen, associate managing director of supply chain food safety operations at NSF International, defines a food quality plan as “the system by which the manufacturer controls the process to ensure desired quality-related outcomes are consistently achieved.” She says quality parameters are defined by brand, consumer expectations and customer requirements, but also by standards of identity codified in regulatory and international standards such as ISO, and in third-party certification program requirements relating to what the quality management system should achieve.

“The documented quality plan identifies the products, processes and quality metrics and their CQPs associated with internal (brand-related) and external (customer-related) requirements,” she says. The quality plan lays out the steps in the process that are critical to achieving the desired quality characteristics and control mechanisms used for adjusting the process as needed to account for variability in conditions and inputs.

“When the manufacturer has evaluated the risks to quality outcomes, control measures must be established and validated, followed by monitoring and regular verification that the control measures remain effective.”

— Carey Allen, associate

managing director of supply chain

food safety operations at NSF

International

She says that similar to a food safety plan, the quality plan encompasses everything from specification development and supplier approval to receiving, handling, processing, and packaging and distribution. The manufacturer must clearly understand the quality-related customer and consumer requirements, and the processes and inputs that impact these characteristics in order to effectively assess risks to these attributes.

“When the manufacturer has evaluated the risks to quality outcomes, control measures must be established and validated, followed by monitoring and regular verification that the control measures remain effective,” Allen says. “With an effective food quality plan, the manufacturer can expect to achieve a reduction in complaints and an increase in overall satisfaction, translating to improved business performance.”

Joe Woloszyn, consultant at JW Quality Consulting, says, “The food quality plan focuses on measurable attributes that affect product quality. It should identify steps in the process that must be controlled and have a critical limit that deems the product acceptable or not.”

Where to begin

Allen says that, in general, the GFSI-benchmarked standards incorporate an expectation that the organization understands and controls the elements of the product and process that are important to the final product acceptability, but safety is also certainly a focus.

“If a supplier has a well-developed and executed food safety plan, 75% of the work of the food quality plan is already done,” she says. “A few of the GFSI-benchmarked certification programs have specifically defined management of quality into its own module or standard to provide more focus on management of customer requirements.”

The size and maturity of organizations tend to be drivers in the adoption of the “quality systems” management mindset as added layers to the food safety management system, she says. Larger organizations may also have the ability to invest in the talent and technologies need to manage complex quality systems. Small operations can certainly manage quality well, she adds, but may not be as likely to adopt a formalized food quality plan.

“I think the consumer often thinks of high quality with ‘artisanal’ small operations, assuming there is more focus on quality due to passion for the product. However, adopting a food quality plan when small can help the company stay on track as they go through expansion to grow the business and remain profitable,” she says.

Lane says the easiest way to develop and implement a food quality plan is to keep the process simple and easy to explain to management or team members. He says this can be accomplished by following the procedures used in the development and implementation of a HACCP plan, including using the same basic concept of the five initial tasks and seven principles of HACCP. Instead of the focus being on food safety, however, the focus is on food quality.

The five initial tasks for a food quality plan include:

- Assemble a food quality team.

- Describe the food and its quality attributes.

- Identify intended use and consumers.

- Develop a flow diagram.

- Verify the flow diagram.

Once the five initial tasks are completed, Lane says to proceed with the same seven basic principles in the development of a food quality plan, including:

- Conduct a quality hazard analysis.

- Identify the critical quality points.

- Establish critical limits.

- Monitor CQPs.

- Establish corrective action.

- Verify.

- Perform recordkeeping.

Similar to when companies develop their HACCP plans or other food safety plans, quality data must be identified and quantified about products or ingredients used, equipment used, processing steps, food packaging, or other aspects and features of products, Lane says.

Woloszyn also says that a food quality plan can be included in a HACCP flow diagram where CQPs can be identified similar to CCPs at various steps of the process. “A similar hazard analysis should be conducted but with a focus on quality versus food safety,” he says.

While creating a food quality plan, it is important to consider company size, end product, processing equipment and other factors. For instance, NSF’s Allen says that the complexity of the organization impacts its ability to control quality. “Physical size of the operation and complexity of the organization structure, operating processes and manufacturing processes are all important to consider when developing a quality plan, the procedures for monitoring, and the training and communication related to executing the plan,” she says. “The more complex the organization, the simpler to execute you must make the plan in order to achieve success.”

Teague notes that smaller companies may not have the personnel or company infrastructure to support a food quality plan, and many customers do not require one—even for larger companies.

Creinin says that as organizations scale, they are faced with different challenges. For instance, small producers are faced with understanding how to scale operations to meet market demand while maintaining consistency. “This typically manifests itself in appropriate capital production investments,” he says. “For larger organizations, their biggest challenge is bringing new products to market, and the internally driven processes to speed these products.”

He says that in both cases, technology can help that happen. Smaller companies need to find technology that will help them scale without having to add excessive process.

“They need to automate data gathering so that, as they scale, they can learn to trust the systems to be able to ensure that the processes work,” Creinin says. “For larger organizations, their challenge is finding process bottlenecks and applying technology to reduce their impact on production.”

In regard to the end product, Teague says that high-risk, premium or ready-to-eat items may require more stringent quality controls. Also, the more complex a process becomes, the more potential threats to quality can emerge.

Allen adds that different equipment can be used to achieve the same quality attributes, but some equipment is easier to control than others or may introduce confounding elements that impact quality over time that are not readily apparent.

Manufacturers should approach the process of developing a quality plan in the same way they would any other risk assessment. Following the steps of HACCP risk assessment is a familiar approach and some of the ground work is already done, in terms of understanding the process.

“Understanding truly what the customer and consumer quality characteristics are is key and must be done first in order to have an effective quality plan,” Allen says.

“Food quality is company-driven, but most often has to respond to customer and consumer demands. Failure to respond to customer and consumer requirements for quality will result in loss of business.”

— Jack Teague, implementation specialist at CAT Squared

Processors should be asking, “What is truly most important to customers, and can you afford to deliver it, or (do you) have the capability to delivery it, in your current process?”

Teague agrees. “Food quality is company-driven, but most often has to respond to customer and consumer demands. Failure to respond to customer and consumer requirements for quality will result in loss of business,” he says.

More about CQPs

According to Teague, “CQPs in a food quality plan are analogous with CCPs in a food safety plan, which means they are points in the process where significant threats to the food quality are controlled to eliminate the threat or reduce the risk to an acceptable level.”

Allen defines CQPs as the output of the risk assessment that identifies the following:

- The quality attributes required by the customer/consumer.

- The processes used to deliver those attributes (equipment, procedures).

- The parameters and metrics required in the process for control (line speed, cooling rates, etc.).

- Those parameters that require control because there is no adjustment down the line that can correct a deviation.

The number of CQPs that are established for any one product depend on the aspects and features that are important to a processor. Lane says CQPs are wide-ranging, including pH, brix, number of broken pieces, color of the product, food packaging features or other characteristics.

“Using color as one example, if your product is supposed to be fireball red candy, then a washed out, faded pinkish candy look isn’t going to represent an individual’s perception of what a fireball red candy should look like. Although the flavor may be spot on target, the fact that the color is off is all the consumer is going to remember,” he says.

Once you have established your CQPs, it is not only important to ensure that they are controlled but also to ensure corrective action and root cause analysis procedures are followed when issues or concerns arise. (See sidebar for an example.)

Fixing BBQ brix fluctuations

Here, Scott C. Lane, CFS, food safety trainer/food safety and quality plan consultant at Eagle Tower Inc., uses an example of a product and its CQP, in this case the brix on an apple barbecue sauce from a well-known manufacturer. He reviews how it was controlled, analyzed, investigated and used to maintain and improve the quality.

During the original product development process, a specific brix was identified by the customer for mouthfeel, taste and product function ability.

During a review of the statistical process control (SPC) charts for the brix of the sauce, it was observed that the brix results fluctuated in an inconsistent pattern when each batch was tested. Individual batch test results all fell within three standard deviations (s=1.94) of the mean (µ=52.45), yet the inconsistency warranted investigation. Although there were no customer complaints, there was always a possibility of a customer complaint due to the product inconsistency between batches.

During a review of the formulation steps on the manufacturing batch record, it was noted that the original mixing sequence added sugar at the end of the batch. Although each batch was brought up to the proper temperature of minimum 185°F and maximum of 190°F, the very small amount of sugar that was added in the last step was enrobing around some of the particulate matter, and not properly dissolving in each of the batches. A batch sample was made in the Product Development Lab altering the mixing sequence of the sugar. This successfully addressed the issue of the sugar enrobing and resulted in consistent brix measurements within one sigma limit.

The manufacturing batch record was changed to add the sugar into the batch after the liquid ingredients and before any dry spices and other ingredients (changing the mixing sequence).

The manufacturing batch record was changed to add the sugar into the batch after the liquid ingredients and before any dry spices and other ingredients (changing the mixing sequence).

This change allowed for the sugar to fully dissolve in the liquid ingredients before the addition of the remaining ingredients and then heating the batch to the minimum required temperature of 185°F and maximum of 190°F.

The change in the mixing sequence has no effect on the food safety of the product. However, it greatly improved the quality of the product.

The brix on all subsequent batches produced with the revised formulation steps on the manufacturing batch record were within one sigma limit.

For more information:

Eagle Tower Inc., scott_eagletower@yahoo.com

CAT Squared, www.catsquared.com

Elemica, www.elemica.com

NSF International, www.nsf.org

JW Quality Consulting, 716-785-1524 or jwoloszyn@jw-qc.com

.webp?t=1721343192)