Beyond Borders: Food Fraud in Global Supply Chains

Conducting a food fraud vulnerability assessment helps identify potential weaknesses in the supply chain and assist in establishing effective controls to mitigate those risks

Food fraud is the intentional and deliberate substitution, addition, tampering, or misrepresentation of food products, food ingredients, and food packaging for economic gain.1 It may impact up to 10 percent of the global food supply, leading to potential losses estimated as high as USD$40 billion annually.2 Fraud primarily occurs at the individual ingredient level rather than at the multi-ingredient product manufacturing level. Depending on its nature and impact, food fraud can quickly escalate into either a food safety or food quality issue.

When a fraud incident poses a risk to human health, it becomes a food safety concern, and when it affects product integrity, it becomes a quality issue. Because food fraud can be difficult to detect until it affects food safety, many such incidents go undocumented. Low incidence reports do not necessarily mean low risk, however, as underreporting or detection challenges can obscure the real magnitude of the problem.

Food fraud can occur in various forms. Common methods include:

- Dilution, substitution, and addition of food ingredients with low-value alternatives or undeclared substances are typically done to increase weight, volume, or enhance sensory attributes. Notable examples include the mixing of extra virgin olive oil with low-quality oils and the addition of Sudan dyes to spices.

- Mislabeling (e.g., misrepresentation of conventional products as organic, non-GMO, kosher, etc.), false claims (e.g., claiming a product is 100 percent apple juice even though the product contains sugar and flavorings), and tampering with expiration dates.

- Counterfeiting results in the production of inferior products that are then marketed as authentic. This is usually done by falsifying brand names, origin, or certification details. For example, in 2020, Spanish authorities seized counterfeit alcoholic beverages that were designed to imitate a well-known brand.

- Diversion of products through unapproved distribution channels by gray market vendors.

Among these, dilution, substitution, and mislabeling are the leading causes of food fraud. They are relatively easy to carry out and can evade standard detection practices. A well-known example is the entry of horse meat into the supply chain as beef in Europe. Counterfeiting and diversion are less frequently encountered, as they often require more sophisticated and coordinated operations.

Trends and Insights: What the Data Suggests

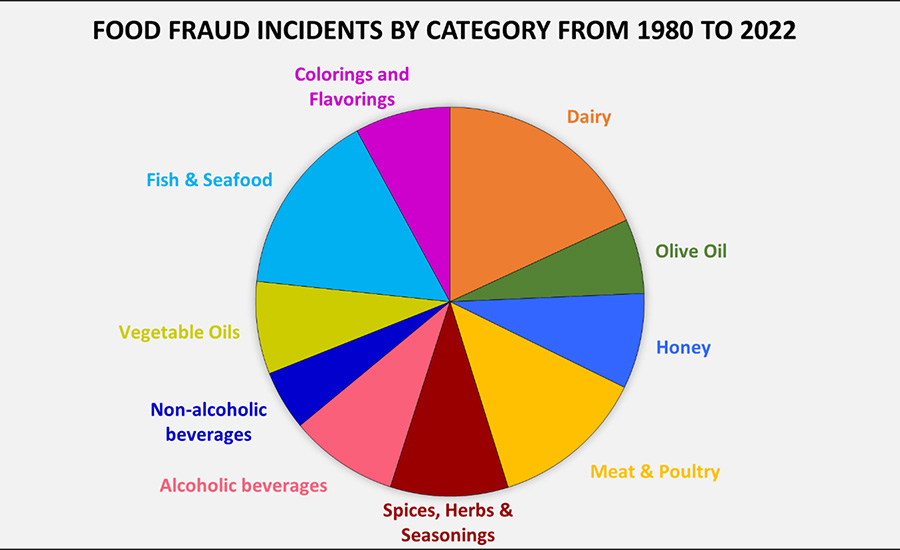

The FOODAKAI Global Food Fraud Index reported an alarming spike in fraud incidents associated with nuts, seeds, and nut-based products in Q1 of 2025,3 which can be attributed to increased commodity pricing for pistachios, walnuts, and almonds. This trend is especially concerning for powdered products due to their granularity and ease of adulteration. The complexity of global supply chains further intensifies the occurrence and difficulty of detection of such cases. Dairy, fish, and seafood continue to be among the highest-risk categories (Figure 1).

As reported in the FOODAKAI Global Food Fraud Index, a sudden rise in fraud, such as dilution and false "natural" claims in non-alcoholic beverages (including soft drinks and infused waters), is particularly alarming and suggests a worsening of the problem in areas previously thought to be under control. Where juice products, coffee, and honey showed encouraging developments in Q1 2025, a few fraud reports were associated with garlic, a subcategory of fruits and vegetables. Now, a rise in category-specific positive trends could be interpreted as an improvement in supply chain surveillance, or they could be indicative of smarter fraud techniques that escape current detection methods. Thus, optimism should be accompanied by caution, as what might seem like progress could ultimately be misleading.

In a recently published report, Everstine et al.4 found that the highest number of food fraud incidents were linked to manufacturing locations based in India, China, the U.S., Italy, the UK, and Pakistan. This demonstrates that the risk associated with a geographical region necessitates measures beyond the presence of policies and regulatory frameworks. The observation that both advanced economies with strong oversight and emerging markets with developing infrastructure are equally susceptible to fraud prompts the consideration of other contributing factors that may be driving this risk.

From a manufacturing standpoint, a high production volume of a specific commodity can increase its vulnerability to fraud. For example, India is the largest producer and exporter of spices and plays a central role in the global spice trade, making it a high-risk country in that category. This does not inherently mean the origin is more fraudulent; rather, it reflects the scale, complexity, and exposure of the supply chain. It can be said that a plausible correlation exists among a commodity's geographical origin, production output, and the nuances of the supply chain.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Mapping Vulnerabilities in the Supply Chain

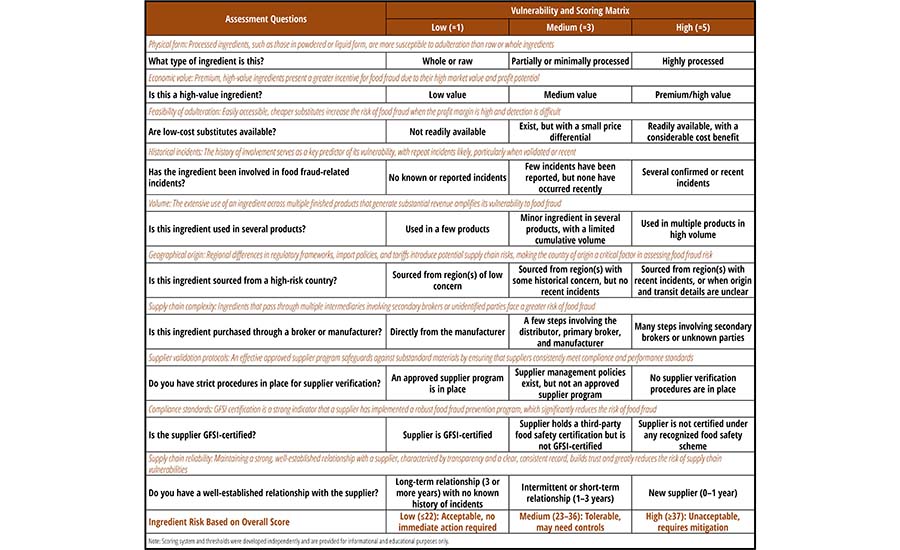

Conducting a vulnerability assessment is a critical measure in preventing food fraud. It is not only a requirement for compliance under U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory standards and Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI)-benchmarked certification schemes, but also a proactive step in safeguarding the integrity of the food system. Such assessments help identify potential weaknesses in the supply chain and assist in establishing effective controls to mitigate those risks.

Organizations can choose to develop their own tools or leverage existing resources, depending on the scale and complexity of their operations. Companies utilizing several ingredients may benefit from a pre-screening process to determine which ingredients would require a comprehensive assessment. For small to mid-sized food manufacturers, a straightforward yet holistic approach can be both practical and effective. This article will discuss one such method, built on a simple, well-rounded criteria, to efficiently guide a vulnerability assessment.

While this approach provides a solid foundation for addressing the various aspects of food fraud risk, the structure of the assessment has been primarily designed to offer informational and educational insights. However, it is fundamentally promising and retains the flexibility for future adaptations by surrendering to a broad scope of revisions to better align with specific organizational needs. Given that some areas tend to carry a greater significance than others in terms of risk evaluation, the probability of incorporating weighted scoring is justified. Introducing additional questions to render a more inclusive representation of vulnerabilities could also stand out as advantageous. Presently, the questionnaire carries three levels of risk: low, medium, and high. However, leaning toward a more conservative approach by establishing an additional high-risk category, particularly when handling an implicated ingredient category, can be viewed as favorable.

Next Steps: Caution and Prevention

Food fraud is not merely a regulatory concern; it is also an ethical one. It undermines consumer trust and threatens the integrity of the global food system. Supply chain vulnerabilities are widely established as drivers of food fraud; however, the greater challenge lies in detecting the concealed, secondary weaknesses that often go unnoticed. Food manufacturers are urged to take proactive measures:

- Adopt product authenticity testing as a standard practice

- Ensure supply chain transparency and complete visibility over the chain of custody

- Conduct sampling of raw materials during onsite supplier visits for laboratory testing

- Maintain a documentation trail tracking material movement from source to destination

- Strengthen awareness through comprehensive employee training programs.

Food fraud prevails quietly among us—unseen, unchecked, and sometimes underestimated. Therefore, it is essential to foster collaboration among academia, industry, and regulators to develop shared protocols, improve database accessibility, and ensure consistency in available resources. Preparation and remaining vigilant to emerging risks are key in mitigating the true extent of the impact of food fraud.

References

- Spink, J. and D.C. Moyer. "Defining the Public Health Threat of Food Fraud." Journal of Food Science 76, no. 9 (November 2011): R157–R163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02417.x.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Economically Motivated Adulteration (Food Fraud)." Current as of August 28, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/food/compliance-enforcement-food/economically-motivated-adulteration-food-fraud.

- Pehlivanis, K. "Sharp Rise in Fraud for Nuts, Dairy, and Cereals: Q1 2025 Findings from the FOODAKAI Global Food Fraud Index." 2025. https://www.foodakai.com/sharp-rise-in-fraud-for-nuts-dairy-and-cereals-q1-2025-findings-from-the-foodakai-global-food-fraud-index/.

- Everstine, K.D., H.B. Chin, F.A. Lopes, and J.C. Moore. "Database of Food Fraud Records: Summary of Data from 1980 to 2022." Journal of Food Protection 87, no. 3 (March 2024): 100227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfp.2024.100227.

- Gendel, S., B. Popping, and H. Chin, H. "Prescreening Ingredients for a Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment." Food Technology Magazine. November 1, 2020. https://www.ift.org/news-and-publications/food-technology-magazine/issues/2020/november/features/prescreening-ingredients-for-a-food-fraud-vulnerability-assessment.

Baidini Ghosh, M.S. is a Corporate Quality Assurance Scientist at Faribault Foods, where she primarily oversees the Organic, Non-GMO Project, and Certified Gluten-Free certification programs. Baidini is trained in HACCP, SQF, and better process control, and is a certified Preventive Controls Qualified Individual (PCQI) for human foods. She holds an M.S. degree in Food Science and Technology from Iowa State University and brings a strong background in food safety systems and regulatory compliance.