From Benchtop to Scale-Up: Food Safety Considerations for New Product Development

A robust product development process builds control into the process so that food safety variables are properly considered

The 2023 International Association of Food Protection (IAFP) Annual Meeting in Toronto, Ontario, Canada brought together more than 3,200 food safety professionals from 53 countries to confer on a variety of topics including cutting-edge research, government updates, emerging issues, and areas of interest affecting the food industry. One notable roundtable featured a discussion on food safety concerns during the new product development (PD) process. The panel of experts included food safety leaders from two global food production companies, a university food science associate professor, a food attorney, and a science advisor from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

These representatives from government, academia, and industry have previous PD experience in various capacities and were able to share insight into this process. Highlights included discussion on the challenges and strategies employed to ensure that food safety considerations are built into this process. Other topics touched on product formulation, packaging, storage/distribution, shelf life, and intended use, which are key attributes that influence the severity and likelihood of food safety hazards. These variables must be carefully considered at each step in the PD process to minimize risk by engineering safety into new products. Thoughtful product development takes time, and companies are often under extreme pressure to expedite this process and quickly take products from the conceptual phase to commercialization. Everyone at the roundtable agreed that having a robust PD process builds control into the process so that food safety variables are properly considered, vital steps are not skipped, and approvals are streamlined to maximize efficiency.

Food Safety Challenges in New Product Development

The idea of new products, formulations with novel ingredients or flavors, clean labeling, and innovative packaging seems like a rather straightforward process. Starting with an initial idea, that new concept moves to the benchtop, where the product comes to life. Once it has successfully been made at a benchtop (small) scale, it pushes forward to pilot plant testing and finally to a commercial launch. However, when bringing an initial concept to life, a variety of challenges can arrive at any stage in the process, causing companies to put a halt to production.

From novel and innovative meat and dairy alternatives to new ways of delivery, the food industry is booming with new startup companies. Many of these businesses started in a household kitchen or were a positive result of an accidental experiment. However, most fledgling companies have very small teams, and they often lack experience in research and development. This experience is key to addressing and solving potential food safety concerns that can arise when scaling up, extending shelf life, and expanding distribution channels.

Many startup companies try to differentiate themselves by launching products with trendy ingredients such as active mushrooms or adaptogenic herbs and extracts. While they might be growing in popularity, these ingredients are newer to the market and may not yet have reliable information available about how to safely use them in food production. New processing technologies that have not been proven safe or validated by government programs and organizations are also being used, opening the door to food safety challenges down the road.1

Mid-size to large companies that have a fully developed Research and Development (R&D) program also face their share of food safety challenges that might look different than their fledgling counterparts, but definitely still exist. Many R&D scientists face pressure to quickly get products to market to meet consumer demands and new trends, or for promotions and limited-time offers. In addition, compensation and bonuses may be contingent on the commercialization speed.

With climate change, political unrest, and other external factors, there may be gaps in supply chains, causing companies to scramble to find replacement suppliers. These suppliers need to go through audits to ensure that they are following good manufacturing practices (GMPs) and are in alignment with their customers. Not all ingredients are made the same by every supplier, nor do they work identically in all applications. Challenges can also include the use of raw materials from other countries. These countries may have traditional ways of preparing food that fail to meet the processor's safety requirements.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

While food safety challenges can arise even before a product leaves the door, we must not forget about the situations that could arise once the product reaches the consumer. It is vital to understand how the consumer will most likely use the product, and if that usage could circumvent the food safety hurdles that have been set into place.

For example, FDA issued a six-state outbreak investigation of Salmonella enteritidis infections in May 2023. After investigation and epidemiologic traceback, data showed that the illnesses were linked to take-and-bake raw cookie dough.2 While the intended use of this product was to be baked at 375 °F (191 °C) for 10–12 minutes to kill potential pathogens, consumers bypassed this critical control step and ate the raw dough, which was contaminated with Salmonella.

Importance of Internal and External Communication

Communication is key to an effective new product development program. Many PD leaders understand the importance of cultivating strong relationships and communication mechanisms, involving a wide variety of internal departments such as marketing, procurement/buyers, operations, and quality assurance. Success relies on having these conversations early in the process to understand concerns, potential delays, or barriers. Small companies might need to look outside the organization to identify these resources and can reach out to university extension, trade organizations, and other food industry experts.

External communication should also be built into the PD process. Customers should be consulted to fully understand their needs and how the product will be used once it is sold. Companies need to draft detailed product specifications to avoid delays, misunderstandings, and product abuse.

For novel ingredients and new processes, it is extremely important to involve the appropriate governmental agency [FDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), etc.] as early as possible, to understand possible regulatory hurdles and build them into the deployment timeline. Agencies want to understand new products/processes before they go to market to ensure that they are safe for the general public and permissible under current regulations.

Although FDA does not require premarket approval for food products, it does have the authority to approve certain ingredients before they are used in food. A few years ago, a major confectionary company produced a new caffeinated candy and sought FDA approval, but only after large-scale production had started. Unfortunately, at the time, regulators deemed that caffeine was not an approved additive for that product, and thousands of pounds of product had to be diverted to the landfill. If FDA had been consulted earlier in the project, then the waste of resources and products could have been avoided. Fortunately, FDA was consulted prior to the market release. If regulators had been blindsided by seeing it for the first time on supermarket shelves, then the situation would have escalated into a recall.

Government agencies have stated that the greater understanding of new products or processes they have, the more likely they will be to evaluate them correctly and avoid rejections due to lack of knowledge or misunderstanding. If a new product involves a novel ingredient or processing aid, submitting early for Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) approval is vital. Having these discussions with regulators will help companies clearly understand what is required for approval and how long the process will take to prevent delays. Many are not aware that there is a voluntary process for registering novel food categories or new processes with FDA. This guidance3 can help product developers understand how to proceed.

Many companies are afraid to undergo this process because they fear sharing confidential information or are nervous to disclose a new venture. The alternative is to risk unnecessary delays or enforcement action once the product has reached the public. Both FDA and USDA actively monitor the market and will reach out to companies if they see something that makes them question product validity or safety.

Designing Food Safety Controls Into The Product

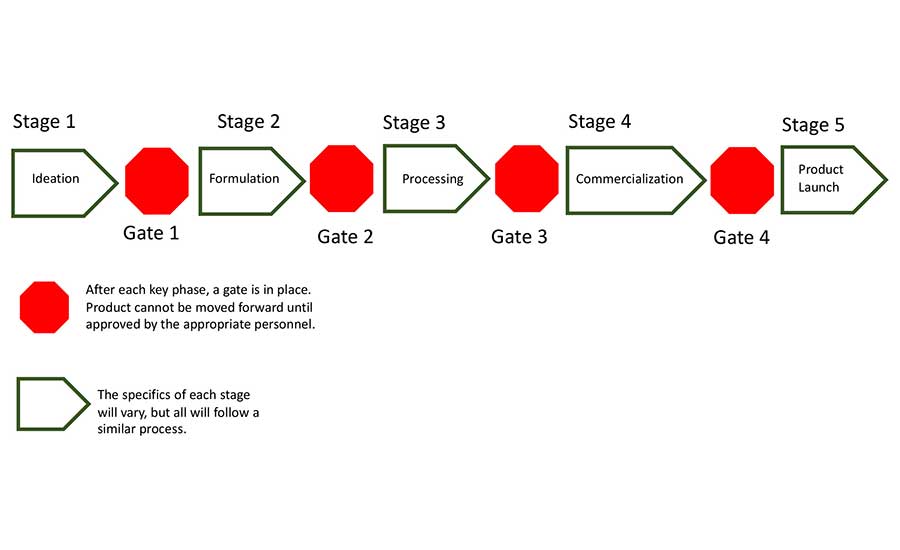

So, you have an idea—then what? How does that idea become a new product launch? Many businesses and companies use an approach called the "phase gate" or "stage gate" process. This linear project management system allows for cross-collaboration, changes where necessary, and a timely concept to product launch.4

In this process, a series of tasks must be completed in each phase/stage in sequential order. After completion, the process or product is reviewed at the "gate" and must be approved by the appropriate stakeholders before advancing to the next stage. While the stages and gates may vary from product to product, depending on budget and resources, they typically follow five key phases (Figure 1):5

- Ideation

- Formulation

- Processing

- Commercialization

- Launch

As the product makes its way through the various stages and gates, it is seen and reviewed by many individuals. To ensure that quality and safety is in place at the time of launch, it is vital to frequently include food safety and quality personnel to give guidance and insight. They should be involved in the conversations taking place at every gate to ensure that quality and safety requirements are being met. This includes using approved external suppliers, upscaling processes, ensuring that critical time/temperatures have been met, and that product can make it safely to the shelves and into the hands of consumers.

Including a Food Safety Quality Regulatory (FSQR) individual in every phase of the process can help identify gaps that may have otherwise been missed. This might include asking PD to use only existing raw materials and suppliers as much as possible to reduce new external approvals, if formulations can be upscaled to a plant level, or if current Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plans are robust enough to control hazards while allowing for flexibility. Other questions may be asked, such as if the process allows for proper heating or cooling, if the product packaging has all required information and identified allergens, or to ensure that product is still safe to consume after one week, one month, or one year.

All of these items are important to consider when moving through the phase gate process of a new product. Many companies utilize technologies and project management software options to manage, assign, and execute this process.

Validation Requirements

The food industry is constantly changing to meet the shifting demands of younger generations and to satisfy new market trends. This evolution often includes the need for novel ingredients and an expansion of existing supply chains. Technological advancements also produce new equipment that can be utilized to transform existing processes and fundamentally change the way food has traditionally been manufactured.

It is vital that these innovations and all labeling/marketing claims are properly validated to ensure that they are appropriate, sustainable, and comply with applicable regulations. Not only do food companies face the danger of regulatory enforcement, but also the marked increase in class-action lawsuits disputing product claims. Claim validation can include proving the health benefits touted on the label or being able to prove the origin of raw materials for certification claims such as organic, GMO free, kosher, halal, etc. Simply undertaking these validation actions are not enough; they must also be documented for future reference.

For larger companies, it is also vital to build validation into mergers and new acquisitions to decrease liability, ensure compliance, and protect the brand's reputation. Companies must use a "trust but verify" mentality to make sure that the new asset has properly validated all existing processes, equipment, and claims to prove they are both appropriate and legally compliant.

Future Innovations and Concerns

The "food scene" is constantly changing with trends popping up one day, only to disappear the next. Product lifecycles have decreased. Food products and food trends have become heavily influenced by social media, the latest health fads, and advertisement. Consumers have been increasingly aware of new and novel items, and an increasing desire to "have it now." This leaves producers with pressure to push product out the door faster and faster.

While the pressure to quicken the pace has increased, companies must not compromise food safety to launch products sooner. A faster product does not always mean a safer product. As the push for quicker product launches escalates, the food industry must continue to follow its established processes, to ensure that the built-in checks and balances work, that food safety programs are accurate, and that only safe products are being launched.

As consumers are browsing aisles for new food products, their eyes are also drawn to "clean labels" with simple ingredient lists, more nutritious ingredients, bioactive compounds, superfoods, plant proteins, live microorganisms, and other enticements. Many of these emerging ingredients are unique and require special care during processing to maintain viability and effectiveness after processing.

Traditional methods such as pasteurization, cooking, baking, and hot-fill processing that have been validated to kill possible pathogenic microorganisms are not able to be used with these specialized ingredients and food products. Therefore, manufacturers are exploring new technologies such as isochoric freezing, cold plasma, and electrohydrodynamic drying to enhance food safety.6,7

In addition to continued testing, validation, and verification on these advanced technologies, consumer education must remain a priority as these technologies continue to advance. With proper education comes greater consumer acceptance that these unfamiliar words and scientific terms are actually making their food safer.

When looking to the future, we must not forget about today. Conducting tests, gathering and analyzing data, and keeping accurate records today can help us in the future. Learning from past mistakes and failings can help the food industry be prepared to avoid food safety issues and become more adaptable to a changing industry.

Conclusion

It has often been said that "it takes a village to raise a child." This proverb can also be adapted to apply to the food industry, as it takes a multitude of people to keep food safe. This includes risk management and how decisions are made with new ingredient selection, formulation, and new processes, in addition to ensuring that vital variables have been considered and the proper approvals are included.

Unique challenges are faced by food scientists and manufacturers in PD when scaling up from initial concept to full production. It takes professionals and experts from all stages of the development process including food safety, retail, food law, and government in new product development to meet these challenges. Communication and problem-solving the many food safety factors and trials that persist are vital when transforming an idea into something safe and delicious to eat.

References

- Innova Market Insights. "Functional Ingredients in the US: Exploring the Growing Demand." 2023. https://www.innovamarketinsights.com/trends/functional-ingredients-in-the-us/.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Outbreak Investigation of Salmonella: Raw Cookie Dough (May 2023)." Current as of July 13, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-salmonella-raw-cookie-dough-may-2023.

- FDA. "Guidance for Industry—Process Validation: General Principles and Practices." January 2011. https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Process-Validation--General-Principles-and-Practices.pdf.

- Scavetta, A. "Phase-Gate Process in Project Management: A Quick Guide." ProjectManager. November 5, 2019. www.projectmanager.com/blog/phase-gate-process.

- Gilbert, K. and K. Prusa. Food Product Development Lab Manual. 2021. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Digital Press. https://doi.org/10.31274/isudp.2021.66.

- "Four Emerging Technologies for Processing Food in 2022." Food Processing, June 20, 2022. www.foodprocessing.com/on-the-plant-floor/technology/article/11287870/four-emerging-technologies-for-processing-food-in-2022.

- Niemira, B.A. "Recent Advances in Food Processing." Food Safety Magazine. October 19, 2020. www.food-safety.com/articles/6805-recent-advances-in-food-processing.

Kory Anderson, M.S., is a Food Scientist at Cargill Inc. She holds a M.Sc. degree in Food Science with an emphasis on Food Microbiology from Washington State University and a B.S. degree in Food Science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Wendy White, M.Sc., is the Food and Beverage Industry Manager for the Georgia Manufacturing Extension Partnership (GaMEP) at Georgia Tech, a state, and federally funded program that helps manufacturing companies increase top-line growth and reduce bottom-line costs through onsite projects, training, and connections to other resources. Ms. White leads GaMEP's food industry services, which include regulatory compliance, HACCP food safety plans, and third-party audit certification preparation. She holds a B.S. degree in Biology and an M.Sc. degree in Food Microbiology from the University of Georgia and is an FSPCA PCQI Human Foods Lead Instructor, an International HACCP Alliance Lead Instructor, and an ASQ Certified Quality Auditor. She is also a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Food Safety Magazine.