What Industry and FDA Are Thinking about FSMA Implementation – Part 2

In this Food Safety Insights column, we continue to present the findings from our most recent survey conducted in January 2019 with 240 food processors about their experiences with the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). As we mentioned in our last column, it has been about 2 years for most companies to execute on the FSMA programs that they have developed, and we wanted to find out more about their experiences, what they have learned over these past 2 years, how they may have had to modify their programs, and their new and developing relationship with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s new inspection and sampling practices.

In this article, we will also hear directly from FDA. We shared our findings with the agency, and we wanted to hear their comments as well. And since we asked processors what they wished FDA understood better, we also asked the agency what they would like to see processors understand better.

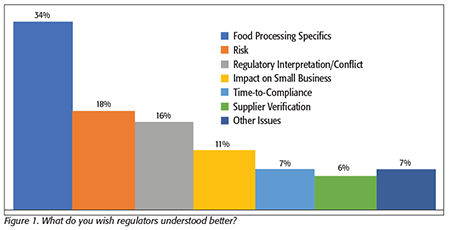

First, as in 2017, we asked what processors wished regulators understood better (Figure 1). Overwhelmingly, the answer was a desire that inspectors better understood their specific processing operations. The processors mentioned that they found that it was difficult for the inspectors to make consistent regulatory interpretations when they were trying to uniformly impose those regulations across diverse processing operations with significantly different processes. One respondent summed up many of the comments by saying, “Every type of processing is different. It would be great for regulators to educate themselves on the types of processing they are inspecting and apply regulations based on the specific risks associated with that operation.”

The second-most-heard request from processors—which is somewhat related to the first—is that they would like to see the regulators have a better understanding of risk. Roughly one-half of these comments were related to a desire to have regulators have a more thorough understanding of the real risks associated with their specific food type or processing systems—making this comment closely related to their request for inspectors to have more familiarity with their food and processes.

The other comments related to the understanding of risk had to do with a desire for regulators to have a better recognition of the points of real risk, where there are likely or probable risks to consumers. Processors also mentioned that they would like to see better recognition of the consumer’s responsibility for proper food preparation and cooking, and how some products—such as raw agricultural products—are different from and far more variable than other processed foods; they also would like to see this better acknowledged by all federal agencies. Processors would like to see regulators recognize that lot-by-lot variability is far higher in many such products, that this condition is normal, and that without flexibility in interpreting requirements, regulators can impose unreasonable requirements on some categories.

Another request came from small businesses. They wanted FDA to recognize that small businesses are just as diligent in wanting to comply with FSMA, but that they needed more time to put their systems in place. Many small processors rely on many people handling multiple tasks for their compliance operations, or, as one processor added, “…More time is needed for smaller companies to comply using our small employee base, where each person may wear many hats and manage multiple programs.” The “juggling” that’s required to get everything done makes it more difficult for small businesses to get every detail right, especially with documentation.

Because larger businesses have dedicated individuals for many of the specific tasks required, these individuals also typically have more time to study the requirements and take training courses than their counterparts in smaller facilities. Small businesses don’t always have the same amount of time to attend conferences or schedule the limited training courses in all the areas that they need to address. If there are areas of food safety risk found, they report that they are ready and willing to accept the inspector’s judgment and conclusions, and to make any needed changes. But in areas of regulatory process, where there are fewer tangible risks involved, such as the details of paperwork and documentation, they’d like to see some more flexibility. One small processor commented, “The high degree of documentation and reporting requirements makes it much more difficult for small businesses to comply with the supplier requirements of the large corporate processors, making it less likely that small businesses can stay in business,” and another added, “The costs and resources required for compliance are relatively much higher for small businesses, making it a substantial burden…” and “…Some of us think the FDA would rather us be out of the business so more processing is done by larger, corporate entities.”

Understanding that FSMA has ushered in not only new regulations but also new enforcement procedures—especially FDA’s practice of collecting more environmental samples during inspections (“FDA swab-a-thons”)—we asked processors if FDA had indeed collected samples. Of those processors in the U.S. and Canada who have had an inspection, 30 percent said that FDA did indeed collect environmental samples, with 70 percent reporting that they had not (Figure 2).

We also asked about changes that processors may have made to their environmental monitoring and sampling plans, especially with the potential anxiety that processors may have felt knowing that FDA would be or may be collecting more samples. Surprisingly, the results this year were very similar to what we heard in 2017, with 53 percent of respondents reporting that their environmental sampling program is “about the same” (Figure 3) compared with 51 percent in 2017. Roughly 27 percent said that they have been collecting more samples, with most of those saying that it helped them prepare for their inspections. One processor in this most recent survey commented, “We’ve been gradually increasing our environmental monitoring..., and this has actually helped us improve effectiveness of sanitation at the facility,” while another said, “…Our environmental sampling program has stayed about the same over the past 2 years, but we did start adding slightly more samples after our recent FDA inspection.”

We also asked processors again about their use of whole-genome sequencing (WGS). The results in this survey were consistent with multiple past surveys that we have conducted, with the overwhelming majority of processors (93%) saying that they are not employing WGS. We asked the few who did indicate that they had used WGS why they used the technology and how it helped their program. Several mentioned that they did not use the technology on a routine basis but did to identify the source of contamination as part of a specific project. These projects were typically described as an effort to eliminate “hot spots” or, as one processor reported, “a project to compare results found in several facilities to identify a source of contamination.” Interestingly, two of the processors who used WGS said that it did not help them identify and find their problem, and they found the data to be less useful than they originally hoped when they started the project. WGS seems to remain a mixed bag of utility for food processors.

We want to express our appreciation to all the food processors and FDA officials who participated in this survey. Food Safety Insights will continue to explore these topics on a regular basis, and we look forward to getting another regular comprehensive update in perhaps another 2 years.

Bob Ferguson is president of Strategic Consulting Inc. and can be reached at insights@food-safety.com or on Twitter at @SCI_Ferguson.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →