Safe Food for Canadians Act Regulations: An Overview

Food processing technologies are continuously undergoing a sea of changes globally. Food supply chains are expanding and becoming more complex. To cope with the new technologies in food processing and face the challenges posed by the complex supply chain, the food laws and regulations must adapt to these changes. Keeping this in mind, many countries have revised their archaic food safety regulations. For instance, in Canada, there were comprehensive food safety regulations in existence prior to the Safe Food for Canadian Act (SFCA) and its associated regulations (SFCRs). For example, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) was established in 1997, which led to the consolidation of all Canadian national food safety enforcement under one agency. Today, the SFCA and its associated regulations are overseen by Health Canada and enforced by the CFIA, creating an overarching national umbrella ensuring the safety of foods. Both the SFCA and SFCRs came into effect on January 15, 2019. Similarly, in the U.S., the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) of 2011 and the subsequent seven new associated regulations modernized U.S. food regulations that had been in place for 70 years, taking a preventive versus reactive approach to food safety.

In Canada, the federal Minister of Health is responsible for establishing policies and standards for the safety and nutritional quality of food sold in Canada and the administration of those provisions of the Canadian Food and Drugs Act that relate to public health, safety, and nutrition. The policies and standards related to food safety are set by Health Canada, a department of the government of Canada that is responsible for national public health. CFIA is responsible for enforcing the regulations pertaining to food, while in the U.S., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) are charged with enforcing food safety.

The SFCRs have consolidated the requirements stipulated in the Canada Agricultural Products Act, the Consumer Packaging and Labeling Act (food related), the Fish Inspection Act, and the Meat Inspection Act. There are 14 sets of regulations in total from these four acts, which are consolidated into one under the SFCRs.

Scope of Oversight

The SFCRs are applicable to food for humans, including the ingredients used in the manufacturing of human food that is imported, exported, and interprovincially traded for commercial purposes. It is also applicable to the slaughter of food animals from which meat products exported or interprovincially traded.

However, the SFCA and SFCRs are not applicable in the following cases:

• Food carried on a conveyance, for example, ferries, airlines, trains, and for use by crew and passengers

• Food intended and used for analysis, evaluation, research, or exhibitions, weighing 100 kg or less, or in the case of eggs, is part of a shipment of five or fewer cases that are each intended to contain 30 dozen eggs

• Food not sold for use as human food (for example, pet food, cosmetics), and labeled as such

• Food imported from the United States onto the Akwesasne Reserve for use by a permanent resident of the reserve

• Foods imported in bond (in transit) for use by crew and passengers of a cruise ship or military ship in Canada

• Food interprovincially traded between federal penitentiaries

What Are the Important Provisions of SFCR?

A review of the new Canadian food safety regulations and comparison with the previous food safety regulations indicated three major changes:

1. Licensing

2. Preventive Controls

3. Traceability

Licensing: Under the provisions of the SFCRs, any food that is shipped or conveyed from one province to another or that is imported or exported must not be contaminated, must be edible, must not consist in whole or in part of any filthy, putrid, disgusting, rotten, decomposed, or diseased animal or vegetable substance; and must have been manufactured, prepared, stored, packaged, and labeled under sanitary conditions.

In order to conduct food business in Canada, CFIA will have to authorize persons to conduct certain activities through licensing; identify food businesses, collect information about the activities of food businesses; and take responsive action when noncompliant activities are found. This is similar to the FDA requirement for food facility registrations for manufacturers both inside and outside of the U.S.; information collected on these establishments enables inspections by FDA to ensure compliance with FSMA regulations.

In Canada, Part 2 of the SFCRs outlines who needs to be licensed by CFIA, the foods and activities for which a license is required and by when, as well as any exceptions. It also establishes the rules regarding trading food internationally and interprovincially.

Regarding import of food into Canada, Section 12(1) of the SFCRs permits importation of food without a Canadian address (fixed place of business) as long as there is an address (fixed place of business) for the facility in a foreign country that has a food safety system assessed and recognized as providing the same level of protection as in the Canadian regulation.

In the U.S., importers are responsible for ensuring the safety of foods imported and the applicable FSMA rules are stipulated in the Foreign Supplier Verification Program (FSVP) rules. Further, it is the responsibility of importers to ensure that food facilities exporting products to the U.S comply with the applicable FSMA rules. For example, facilities processing/manufacturing food for humans must comply with the Preventive Controls for Human Food rules.

Food that is exported from Canada must also meet SFCR requirements. A person is permitted to export a food that meets a foreign country’s requirement that is different from the SFCR requirement only if the food was prepared by a license holder under sanitary conditions. The person is required to keep written documents that substantiate the foreign requirements have been met and the food must be clearly labeled for export as described in the SFCRs.

Preventive Controls: The requirements for a preventive control plan (PCP) are stipulated in Part 4 of Canada’s SFCRs. A PCP is a document that details how risks to food and to the humane treatment of food animals are identified and controlled. The PCP also includes elements relating to packaging, labeling, grading, and standards of identity. The preventive controls requirements apply to license holders as well as persons who may not need a license to conduct their activities. For example, the preventive control requirements apply to growers and harvesters of fresh fruits or vegetables, and persons who handle fish in a conveyance for export or interprovincial trade. The preventive controls related to food safety are based on the Codex Alimentarius General Principles of Food Hygiene: CAC/RCP 1-1969. The preventive controls related to the humane treatment of food animals from which meat products are derived are aligned with the recommendations of the World Organization for Animal Health’s Terrestrial Animal Health Code – Slaughter of Animals.

U.S. food manufacturers who fall under FDA’s requirements have a preventive control requirement as well. Formerly known as HACCP, or Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points, the requirements were strengthened under FSMA and are now known by the commonly used industry acronym “HARPC,” or Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls.

Much like FSMA’s Preventive Control requirements, Part 4 of Canada’s SFCRs includes:

Division 1: Interpretation and Application. Provides the definitions specific to Part 4 and its application.

Division 2: Biological, Chemical and Physical Hazards. The determination and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards requires the determination and control of all biological, chemical, and physical hazards that present a risk of contamination to the food.

Division 3: Treatments and Processes. Requires a scheduled process to be applied to a low-acid food packaged in a hermetically sealed container if it is not kept refrigerated or frozen after processing.

Division 4: Maintenance and Operation of Establishment. Requires that establishments be maintained and operated in a way that meets the preventive control requirements (sections 50 to 81 of the SFCRs).

Division 5: Investigation, Notification, Complaints, and Recall. Requires an investigation if a potential noncompliance or food safety issue is identified as well as the immediate CFIA notification and action when there is a risk to human health. Like FSMA, written procedures must be in place to handle any and all investigative complaints and recall procedures must be in place and tested for quick removal of affected foods from the distribution chain.

Division 6: PCP. PCPs for both SFCR and FSMA requires a food manufacturing license holder to prepare, keep, and maintain a written PCP that meets the requirements of their respective regulations. Details on the SFCRs can be found in section 89 and in FSMA in Section 415.

Traceability: Traceability requirements for both SFCRs and FSMA are based on Codex Alimentarius principles—tracing of food forward to the person to whom the food was provided and back to the immediate supplier(s) of the ingredients or packaging used in producing the final food. Details of who needs to comply with the traceability requirements; what information must be set out in traceability documents to identify the food (such as the common name of the food and lot code or other unique identifier) as applicable and how long traceability documents must be kept; and when the documents must be provided are all stipulated in the regulations—Part 6 of SFCR and Section 204 of FSMA.

Commodity-Specific Requirements

In addition to the requirements mentioned in the SFCRs, Parts 4 and 5, Part 6 of the regulation outlines specific requirements for the following products: dairy, eggs, processed eggs, fish, fresh fruits and vegetables, and meat products and food animals. In the U.S., these commodities are regulated by USDA.

Compliance Timelines

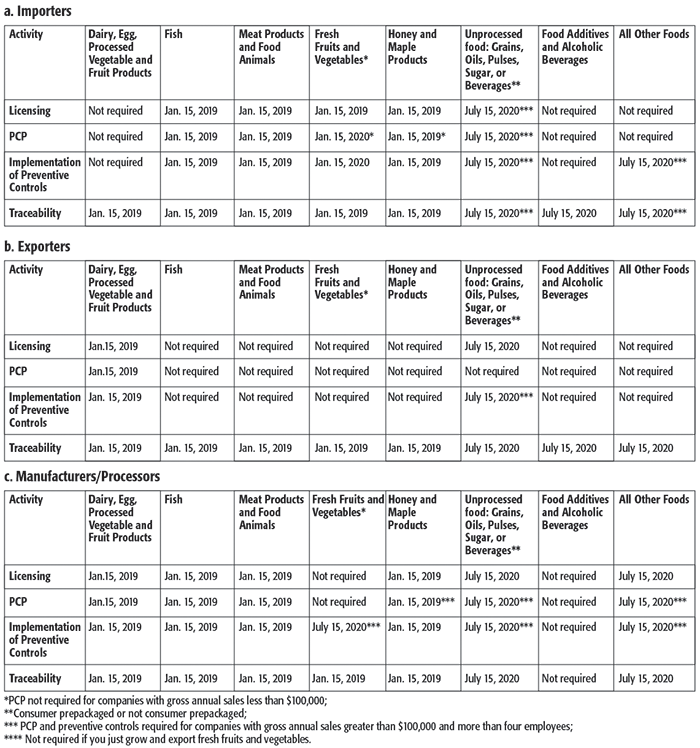

Compliance dates for SFCR and FSMA are well underway with many dates already having passed. Some key dates for the SFCRs are provided in the table.

The information provided in the table regarding timelines is not exhaustive. Readers are requested to visit the CFIA website (www.inspection.gc.ca) for additional information.

For the U.S., almost all compliance dates for enforcement of the FSMA regulations have past, there are a few still pending. These are listed below:

• FSVP for importers whose very small business foreign supplier is subject to the Produce Safety rule including those eligible for a Qualified Exemption – July 27, 2020

• Produce Safety regulation – small farms with remaining water requirements – January 26, 2021

• Intentional Adulteration for very small businesses – January 26, 2021

• Additional rules coming due between 2022–2024 focus on the Produce Safety rule

In summary, the requirements of the SFCRs are very similar to the provisions of FSMA with some key differences as outlined above. Food manufacturers doing business in or with either country may find additional opportunities as well as regulatory challenges just across the border. It is critical that food companies operating in either Canada or the U.S. or are exporting products into either market have a strong regulatory understanding of this new landscape. One way to achieve this understanding and avoid mistakes that can cost your company significant time and money is to employ a competent consultant to bridge any regulatory gaps, ensuring operational success in both countries.

Ramakrishnan Narasimhan is an independent consultant with the EAS Consulting Group, LLC. He is a knowledgeable and competent professional with over 35 years of management experience in the manufacturing sectors pertaining to food, pharmaceutical, and dietary supplement industries. He has wide ranging experience in designing, developing, guiding, and auditing customized and standard product safety and quality system standards.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →