The Importance of a Good Food Safety Program to Control Norovirus

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), norovirus is responsible for over 50 percent of foodborne illnesses in the U.S. In recent years, a majority of foodborne norovirus outbreaks occurred in restaurants, often related to an infected employee practicing poor personal hygiene and subsequently handling food.[1]

In addition to negative health impacts for employees and patrons, a norovirus outbreak can have significant financial and public confidence consequences. It’s essential to understand this virus, its potential effect on your restaurant, and how you can help reduce the likelihood of an outbreak.

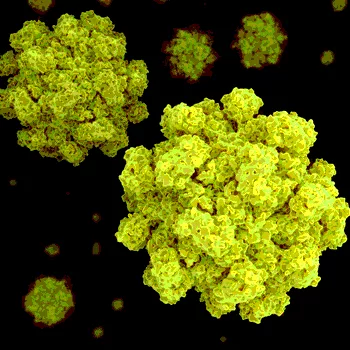

What Is Norovirus?

Sometimes called the “stomach flu,” norovirus only infects humans. It is the most common cause of acute viral  gastroenteritis around the world and the most common cause of foodborne illness in the United States.[2] Unlike some other infectious diseases, we can get norovirus time and again, and the average person will experience a norovirus infection five times in their life.

gastroenteritis around the world and the most common cause of foodborne illness in the United States.[2] Unlike some other infectious diseases, we can get norovirus time and again, and the average person will experience a norovirus infection five times in their life.

Norovirus symptoms usually appear 12 to 48 hours after first exposure, lasting approximately 1 to 3 days. Common symptoms are diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and stomach pain. People with norovirus are most contagious when they are sick, and for a few days after they feel better.

How Is It Spread?

Norovirus is shed in the stool and vomit of infected people. It can quickly spread to hands and surfaces and is easily transmitted by close contact with infected individuals. However it reaches a person, the virus must be taken in by mouth to infect them.

Food and water can become contaminated when prepared or served by an infected food worker or by contact with contaminated surfaces. Outbreaks often occur in places where people gather and/or share food, such as in restaurants, healthcare facilities, and schools.

Foods often associated with foodborne norovirus outbreaks include fruits and vegetables, molluscan shellfish (oysters and clams), and ready-to-eat (RTE) foods, which require a lot of human handling just prior to eating. RTE foods (e.g., salads, hand-sliced deli meats) are the most common cause of illness, usually contaminated by an infected food handler practicing poor personal hygiene. Foods may also become contaminated through contact with a surface that harbors the virus and before or during harvest—for example, oysters harvested from water contaminated with human sewage, or vegetables irrigated with contaminated water.

Why Should You Be Concerned?

Looking at the last few years, foodservice establishments were the main source of norovirus outbreaks.[3] In fact, when a source was found, 70 percent of the time, it was an infected food worker, and in over half of these cases, the person was touching RTE foods with bare hands.

One in five foodservice employees reported working while sick with vomiting and diarrhea, and in general, foodservice employees fail to wash their hands as frequently as recommended.[4]

Norovirus cannot be completely inactivated by many common sanitizers and disinfectants used at manufacturer recommended concentrations and/or contact times. It is possible for the disease to recur even after thorough cleaning and disinfection.[5]

Preventing the Spread of Norovirus

Food safety managers and other staff members play important roles in controlling the spread of norovirus.

For food safety managers:

1. Design a food safety plan that considers norovirus. For example:

• Ensure handwashing stations are readily available and stocked at all times

• Clean all restrooms frequently and regularly

• Have written guidelines for the cleanup of vomiting or diarrhea episodes

• Select disinfectants with anti-noroviral claims but be aware that efficacy claims do not always mean the product eliminates the virus completely. It is best to clean first, sanitize next. Ensure employees applying these products are knowledgeable in their safe use, effective concentrations, and contact times

• Consider the whole facility in food safety planning—how people come and go in food preparation areas, what surfaces are most touched, etc.

• Consider unintended consequences, such the potential for virus spread with improper cleaning or disinfection, or how to respond to unexpected customer behaviors that might promote contamination

2. Educate staff in good food safety practices, norovirus symptoms, and ways to control the virus. Having a certified kitchen manager and other staff members certified in food safety was found to protect against foodborne outbreaks in general, when researchers compared restaurants that had and had not experienced foodborne outbreaks.[6] Train new employees before they begin to work and provide refresher training to assure continued good practices.

3. Observe what food safety procedures employees are performing, making adjustments and providing guidance when problems are identified. For example, make sure employees are washing their hands properly as often as they should be, and are disinfecting surfaces correctly, with the right product, using recommended practices.

4. Exclude sick employees for at least 24 hours after their symptoms resolve. A work environment that provides paid employee sick leave and promotes employee reporting of symptoms is important for U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Code compliance. Since the virus can still shed after symptoms have subsided, temporarily reassign employees to jobs with no direct food contact.

For staff members:

1. Stay home if you have norovirus symptoms and for at least 24–48 hours after symptoms have ended. Always let supervisors know when you are ill.

2. Practice regular hand hygiene consistent with the FDA Food Code and CDC guidelines. For example, avoid bare-hand contact with RTE foods and always wear gloves, changing them frequently. Wash hands for at least 20 seconds. Scrub hands for 10 to 15 seconds under clean, running water with an appropriate amount of cleaning compound advised by the product manufacturer. Rub hands together vigorously—paying attention to fingertips, areas between fingers, and under nails—before rinsing and thoroughly drying.[7]

3. ALWAYS wash hands after using restroom facilities.

4. Clean and sanitize utensils and surfaces properly and regularly.

Being prepared with a good food safety plan, an educated workforce, and a focus on good hygiene and sanitation will not only go a long way to controlling norovirus, but other microorganisms causing foodborne illness as well.

GOJO Industries, Inc. is the inventor of PURELL® hand sanitizers and the leading global producer and marketer of skin health and hygiene solutions for away-from-home settings.

References

1. www.cdc.gov/norovirus/php/illness-outbreaks.html.

2. journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001999.

3. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6322a3.htm?s_cid=mm6322a3_w.

4. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/norovirus/.

5. www.cdc.gov/Mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5646a2.htm.

6. www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ehsnet/plain_language/differences-restaurants-linked-to-outbreaks.htm.

7. www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/RetailFoodProtection/FoodCode/ucm374275.htm.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

.webp?t=1721343192)