Proper Hand Washing: A Vital Food Safety Step

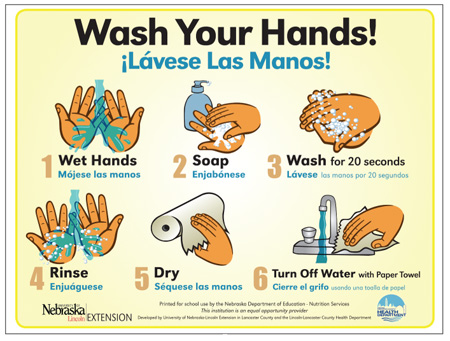

“Wash Your Hands Before Returning to Work.” It’s a familiar sign seen by employees on a daily basis (see Poster). However, do employees really wash their hands? If they do wash their hands, is the washing being done properly? When and where do they wash their hands? Various studies indicate that proper hand washing doesn’t occur as regularly or as thoroughly as needed.[1,2] Depending upon the type of food facility, 33% to 73% of the facilities were out of compliance with proper hand washing procedures.[3]

The Retail Food Sector

Before delving further into the subject of hand washing, it would be best to review the status of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Code, which is oriented to the retail food sector. The latest version of the Food Code was produced in 2009, but there are versions of the code dating back to 1993. Before 1993, there were several model sanitation ordinances presented by the United States Public Health Service. This situation is significant as the Food Code is not a federal law or regulation. The Food Code is a set of recommendations presented by the FDA as being the best current knowledge regarding the proper handling of food at the retail level. The states and territories of the United States have the authority to establish laws and regulations that dictate what procedures are appropriate for retail food entities. Forty-nine of the 50 states and three of the six territories have adopted individual food codes based on some version of the FDA Food Code. Thus, the specific requirements can vary within states and territories.

Controlling contamination on workers’ hands is one of the five important interventions cited by the FDA Food Code to protect public health. To achieve this goal, the Food Code relates a specific hand washing procedure coupled to situations and locations wherein hand washing is to be performed.

How to Wash

The procedure food handling employees are to use to clean their hands and exposed areas of their arms (including prosthetic devices) is as follows:

• Rinse hands under clean, warm, running water.

• Apply an amount of cleaning compound as recommended by the manufacturer.

• Rub hands together vigorously for 10 to 15 seconds while ensuring that soil is removed from under the fingernails and from the surfaces of the hands and arms, including prosthetic devices.

• Thoroughly rinse hands under clean, running water.

• Immediately follow with a thorough drying using single-use disposable towels or a continuous towel system that supplies a new towel at each use or a heated air, hand drying device or a pressurized air blast.

Many studies have been conducted to evaluate hand washing techniques.[1,4] The following general observations were noted:

• The use of 3 to 5 ml antiseptic soap was sufficient; more than 1 ml non-antiseptic soap did not enhance cleaning.

• A washing duration of 5 to 30 seconds can be effective.

• Mechanical action aids in the reduction of transient microorganisms.

• Washing for 2 minutes removes only 3% more transient microorganisms than washing for 15 seconds.

• Washing in warm water (120 °F) removes more microorganisms than washing in cool water (70 °F).

• Washing for 3 minutes actually results in greater microbial counts as resident organisms (those present deeper in the skin) are brought to the surface.

• The presence of rings on the fingers may or may not result in greater bacterial counts on the hands after

washing.

• The residual effects of antimicrobial products depend upon the chemical composition.

• Hot air dryers may or may not increase the bacteria population on the hands.

• The use of single-use paper towels and clean single-use cloth towels aid in the reduction of bacteria.

• Complete hand drying is critical to reduce recontamination.

• Roll-type cloth towels are a source of recontamination.

• Buttons, levers and crank-on towel dispensers are sources of recontamination.

• Automatic hand washing machines produce more consistent and effective results.

The use of gloves can lessen the frequency and effectiveness of hand washing.

• Gloves can be as significant a source of contamination as hands.

• Gloves tend to be changed less frequently than actually needed.

When to Wash

The Food Code states that employees are to wash their hands and exposed arms in the below situations:

• Immediately before working in food preparation where exposed food, clean equipment and utensils or unwrapped single-service or single-use articles are present.

• After touching bare human body parts other than clean hands or arms.

• After using toilet facilities.

• After caring for or handling any service or aquatic animals.

• After coughing, sneezing, using a handkerchief or tissue, using tobacco, eating or drinking.

• After handling soiled equipment or utensils.

• During food preparation to prevent cross-contamination when changing tasks.

• When switching from working with raw to ready-to-eat food.

• Before donning gloves for working with food.

• After any activity that contaminates the hands.

However, research[1] has shown that washing the hands more than 25 times per day can result in higher microbial counts. This situation occurs because the protective barriers inherent in the skin are damaged. Thus, the frequency of hand washing must be evaluated to ensure detrimental effects are avoided.

Where to Wash

Food employees must perform the washing steps in a designated hand washing sink or an approved automatic hand washing facility. Employees can’t clean their hands in a sink used for food preparation, in a ware (implements, dishes, pans) washing sink or in any type of service sink.

Food Handler Training

Based upon the preceding requirements, training of food handling employees regarding hand washing procedures and monitoring of their activity are of prime importance.

Unfortunately, several barriers exist that negatively impact hand washing activities. Employees may be pressed for time, there may be inadequate facilities or supplies or management may not show support.[5] Food safety training alone does not promote the needed level of proper hand washing. Green et al.[2] showed that appropriate hand washing was more likely to occur in restaurants where hand washing sinks were more numerous and the sinks were in the worker’s line of sight. Required hand washing was less likely to occur when employees were busy and when gloves were utilized. In Minnesota, Allwood et al.[6] related that only 52% of the persons in charge could demonstrate the proper hand washing procedure described in the food code. In the same study, 48% of the food workers could demonstrate the proper procedure. Whatever the reason, without proper routine training, supervision and commitment, employees will not realize the importance of hand washing, and food contamination can easily be the result.

Employee training can be accomplished in-house by a knowledgeable staff employee who has been previously trained. Educational materials, including digital video recordings, can be obtained from federal food safety agencies, state or local health departments or from commercial sources. Additional visual training aids such as “Glitterbug,” “GermJuice” and “GloGerm” provide immediate stimulus by simulating the presence of contamination on hands and arms after their surfaces have been washed–unclean areas will glow! If the employer does not desire or does not have the expertise to perform the needed training, there are entities that can provide assistance. An internet search will produce many choices.

Food Producers and Processors

Because many foods are consumed raw, it is imperative that the commodities supplied to the retail food sector be free of contamination. One would imagine that similar codes and regulations exist for foods supplied by producers and processors. While there are certain federal and state requirements for foods such as juices, meats, eggs, dairy products and processed foods, commodities such as fresh fruits and vegetables do not have a set of comprehensive food safety requirements at the present time.

The Code of Federal Regulations states that foods produced must not be contaminated. To promote safe foods, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the FDA emphasize the use of procedures that are termed Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs). The former practices apply to the crops while they are in the field, while the latter applies to the commodities as they are being processed and shipped to the retail sector.

The GMP procedures related to hand washing are present in the federal regulations (21CFR 110.10). Employees are required to wash their hands and arms thoroughly, but no specific steps regarding the hand washing process are present. There are no federal codes related to GAPs, but there are guidelines available from the USDA, educational institutions and commercial entities. These guidelines include information regarding the need for hand washing, but are again general in content. For example, the guidelines cite the need for clean, potable water, a cleaning agent, a clean sink and a sanitary drying system. There is also information on when hand washing is to be performed. There are, however, few or no instructions regarding the proper method of hand washing.

To address the lack of specific standards and to ensure the minimization of sources of food contamination, many producers and processors have adopted the hand washing procedures presented in the FDA Food Code or similar procedures of other entities that specify certain steps to follow. These procedures are usually posted adjacent to all hand washing stations to remind employees of the proper method. Supervisors then randomly observe employee practices and retrain employees as needed.

Consumer Practices

Food safety considerations regarding hand washing are not confined to foodservice workers or food production and processing employees. Foods can be readily contaminated by the consumer while in a retail location or at home.

Various studies have shown that the rate of hand washing of the general public subsequent to toilet use ranges from 67% to 88%, with the inclusion of soap being even less at 58% to 72%.[7-9] By gender, women wash their hands more frequently than men (92% and 81%, respectively) and use soap more often (77% and 66%, respectively). When preparing food in the kitchen, the general public fares even worse with only 24% to 52% practicing some type of hand washing prior to handling food.[10-13]

The above situations occur even though many organizations have actively promoted personal hygiene to the public (e.g., FDA, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USDA, Fight BAC!, the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund). Finding a method to modify human behavior is a challenge not easily met, and it takes specialized approaches. For example, stimulating hand washing in adult men is best accomplished by orienting the message to a reaction that produces disgust. Women, on the other hand, responded better to a message based on knowledge.[14]

It is generally accepted that children are more receptive to new ideas than are adults. In the classroom, food safety topics can be presented in a manner that both instills the idea and modifies the child’s behavior to implement the idea. Internet sites, such as foodsafety.gov and safefood.eu, present food safety educational materials that are oriented to various age groups of children.

Conclusions

Proper hand washing is a critical but often overlooked intervention step in the prevention of foodborne illness. When the entire workforce is knowledgeable about and committed to proper hand washing, the entity, be it retail or wholesale, will avoid costly food safety problems. Educating the consumer in the utilization of proper hand washing is a critical, but very difficult, goal to achieve. Perhaps the continuous promotion of food safety education in the schools will produce future generations that are more aware of simple but effective measures that can reduce illness.

Allan Pfuntner, MA, REHS, is a food safety consultant in Riverside, CA. He can be reached at apfuntner@msn.com.

References

1. Guzewich, J. and M.P. Ross. 1999. Evaluation of Risks Related to Microbiological Contamination of Ready-to-eat Food by Food Preparation Workers and the Effectiveness of Interventions to Minimize Those Risks. USFDA/CFSAN White Paper. September.

2. Green, L.R., V. Radke, R. Mason, L. Bushnell, D. Reimann, J.C. Mack, M.D. Motsinger, T. Stigger and C.A. Selman. 2007. Factors Related to Food Worker Hand Hygiene Practices. J Food Prot 70:661-666.

3. Palumbo, M.S., J.R. Gorny, D.E. Gombas, L.R. Beuchat, C.M. Bruhn, B. Cassens, P. Delaquis, J.M. Farber, L.J. Harris, K. Ito, M.T. Osterholm, M. Smith and K.M.J. Swanson. 2007. Recommendations for Handling Fresh-cut Leafy Green Salads by Consumers and Retail Foodservice Operators. Food Prot Trends 27:892-898.

4. Patrick, D.R., G. Findon and T.E. Miller. 1997. Residual Moisture Determines the Level of Touch-contact-associated Bacterial Transfer Following Hand Washing. Epidemiol Infect 119:319-325.

5. Pragle, A.S., A.K. Harding and J.C. Mack. 2007. Food Workers’ Perspectives on Handwashing Behaviors and Barriers in the Restaurant Environment. J Environ Health 69:27-32.

6. Allwood, P.B., T. Jenkins, C. Paulus, L. Johnson and C. Hedberg. 2004. Hand Washing Compliance among Retail Food Establishment Workers in Minnesota. J Food Prot 67:2825-2828.

7. Hyde, B. 2000. America’s Dirty Little Secret–Our Hands. www.washup.org.

8. Garbutt, C., G. Simmons, D. Patrick and T. Miller. 2007. The Public Hand Hygiene Practices of New Zealanders: A National Survey. N Z Med J 120:U2810.

9. Anderson, J.L., C.A. Warren, E. Perez, R.I. Louis, S. Phillips, J. Wheeler, M. Cole and R. Misra. 2008. Gender and Ethnic Differences in Hand Hygiene Practices Among College Students. Am J Infect Control 36: 361-368.

10. Altekruse, S.F., D.A. Street, S.B. Fein and A.S. Levy. 1996. Consumer Knowledge of Foodborne Microbial Hazards and Food-handling Practices. J Food Prot 59:287-294.

11. Anderson, J.B., T.A. Shuster, K.E. Hansen, A.S. Levy and A. Volk. 2004. A Camera’s View of Consumer Food-handling Behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc 104:186-191.

12. Garayoa, R., M. Cordoba, I. Garcia-Jalon, A. Sanchez-Villegas and A. Vitas. 2005. Relationship between Consumer Food Safety Knowledge and Reported Behavior among Students from Health Sciences in One Region of Spain. J Food Prot 68:2631-2636.

13. Gilbert, S.E., R. Whyte, G. Bayne, S.M. Paulin, R.J. Lake and P. van der Logt. 2007. Survey of Domestic Food Handling Practices in New Zealand. Int J Food Microbiol 117:306-311.

14. Judah, G., R. Aunger, W. Schmidt, S. Michie, S. Granger and V. Curtis. 2009. Experimental Pretesting of Hand Washing Interventions in a Natural Setting. Am J Public Health 99:S405-S411.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →