How Simple Microbiological Truths Provide Insights for Understanding and Solving Practical Problems

There is much in the tried-and-true past that informs us of our ability to progress with food safety and food quality microbiology

In recent years, there have been profound breakthroughs in understanding the genetics and molecular biology of microorganisms. However, with these breakthroughs, it seems that some of the practical implications of older, basic truths that profoundly inform safety and quality may have been forgotten (or missed in the first place). This article highlights some of these truths and refutes some contemporary false assumptions.

While it is always good to challenge discoveries, there is much in the tried-and-true past that informs us of our ability to progress with food safety and food quality microbiology. This article discusses the practical value of some older, seemingly trivial facts in microbiology that have vast importance in solving and resolving practical contamination problems. Outlined below are some principles that should never be forgotten.

Bacteria are Very, Very Small

The fact that bacteria are small may seem obvious or trivial, but it has profound implications for many things, including equipment design, maintenance practices, bacterial persistence, the efficacy of bactericidal treatments, testing, sampling plans, etc. Since bacteria are small, we often think of them as two-dimensional. For example, Salmonella cells are each about 2 microns long by 1 micron wide, but they, like us, are three-dimensional. Imagine a human that is 2 meters tall. This is a million-fold difference, but only in one dimension. Therefore, such bacteria are volumetrically 1 million × 1 million × 1 million times smaller than such a person, or 10-18 times smaller than humans. Salmonella should, therefore, be about 1.57 cubic microns. Imagine a food production facility that is 1 million cubic feet (ft3) of space. Such a facility would need to have an area of only 50,000 square feet (ft2) with 20-foot ceilings to take up 1 million ft3 of space. Note that 1 million ft3 equates to 2.8 × 1022 cubic microns. Now imagine such a space full of equipment. There are plenty of places for Salmonella to hide!

Think of areas such as the inside of a rough weld, drain, or hollow support structure; underneath a tack-welded plate on equipment or a door jamb; on overheads, walls, or false ceilings; and a multitude of other areas that can entrap residue and organisms but are inaccessible for routine cleaning. Those who design and maintain equipment and food processing facilities and those who design environmental monitoring programs (EMPs) should take note. "Out of sight, out of mind" is a bad paradigm, but all too common. Not being able to see an organism inside a crack does not mean that it is not present. This condition worsens if these entrapped microbes have moisture to facilitate their growth, as will be explained below. Many equipment designs preclude effective cleaning because they entrap moisture.1

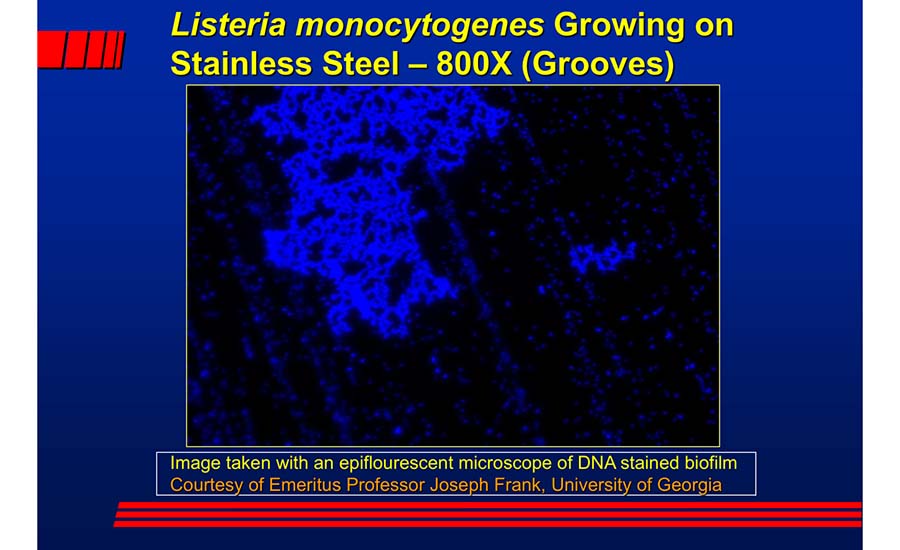

Figure 1 shows a photomicrograph of a biofilm of Listeria monocytogenes on stainless steel. Each small blue dot shows where these organisms are residing in microscopic groves.

Principles of Microbial Growth in Food Processing Facilities

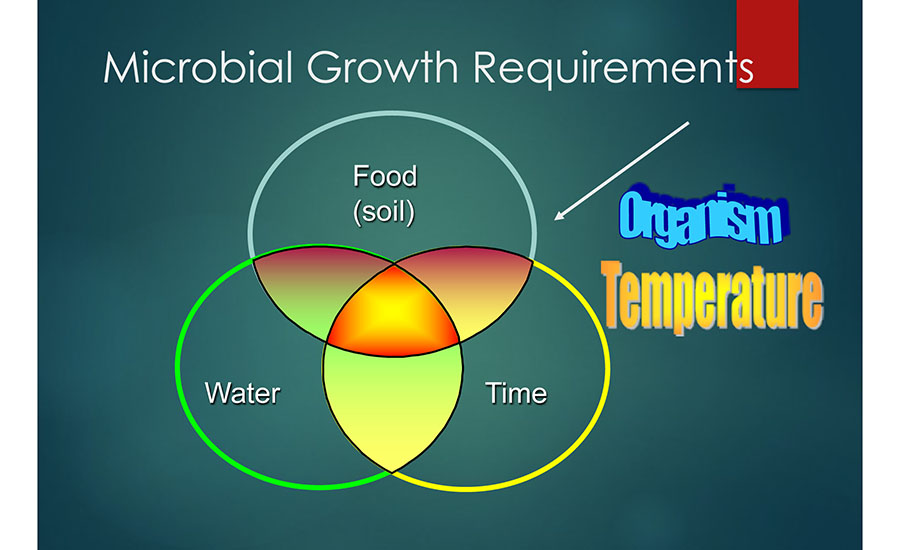

It is impossible to maintain a sterile food processing plant, but it is possible to control microbial growth. It has been stated that microorganisms require several things to grow including water, nutrition, pH, growth-conductive oxidation reduction potential (ORP), temperature, time, presence or absence of inhibitors, and interactions between microorganisms.1,2 Focusing on three key elements has been proven to be helpful: moisture, nutrition, and time (Figure 2). Temperature is also listed in Figure 2, but most food processing facility environments have the broad range (e.g., approximately 0 °C–50 °C) that is conducive to microbial growth.

Figure 2 also contains the term "organism." Organisms, such as Listeria and Salmonella, are regarded as widespread in the natural environment and can readily enter food processing facilities by a multitude of means (e.g., roof leaks, drain/sump backups, ingress from humans, negative pressure, poorly designed HVAC systems, etc.).

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Moisture is the most important of the factors that can contribute to microbial growth in the processing environment, as moisture is essential for microbial growth and is easier to control. The control of water is critical, especially in low-moisture processing facilities.3,4 Seeking out places wherein moisture, including condensate and humidity, can be entrapped is a good place to start when building an EMP or conducting a microbiological investigation.

Microorganisms Require Few Things to Survive

We know that some microbes, such as Salmonella and Listeria spp., can survive in dry environments for years.5 Although moisture is necessary for microbial growth, it is useful to recognize that bacterial heat resistance is greater in substances or on surfaces that contain little moisture as compared to moist or wet conditions. Thus, the question, "What temperature will kill an organism?" is not correct. When referring to killing microbes, the context is killing populations, not individuals.

Furthermore, microbes will die or survive at different rates in products or on environmental surfaces that contain different amounts of moisture. Microbial populations in biofilms also die at different rates than microorganisms that are freely suspended. This is discussed in more depth later in the article.

There is No Such Thing as 'Zero' in Microbiology

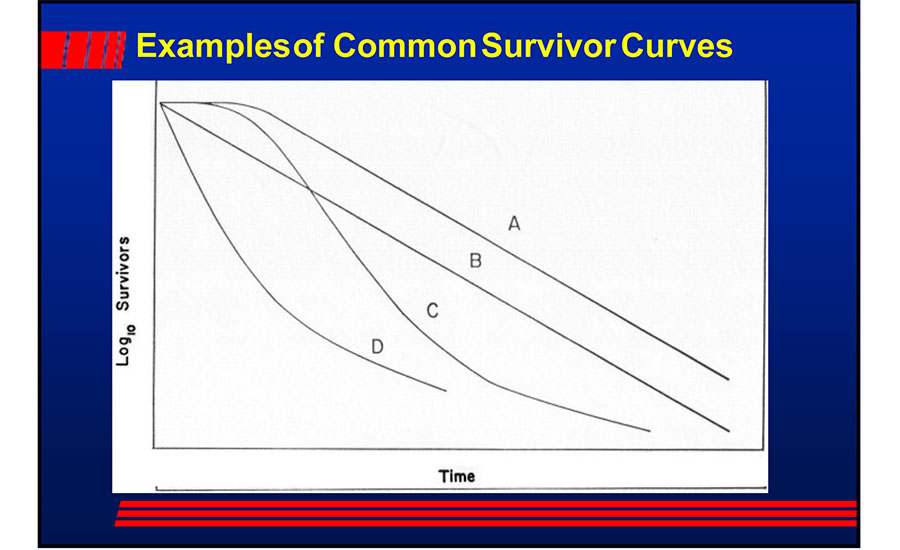

Examples of logarithmic decline of microbial populations follow. All of these are on a logarithmic scale. Figure 3 shows a bacterial log reduction plot over time at a given bactericidal temperature. One could expect to see these types of plots with other types of microbicidal treatments.

Subjecting 100 organisms per sample to a 5-log reduction treatment means that 1 out of 1,000 such samples will be contaminated if the reduction is perfectly log linear (see plot "B" above). Theoretically, a microorganism will survive even a pasteurization treatment and end up in the pasteurized product or worse, attach and form a biofilm in the regenerator section. Once a microbe gets into the pasteurizer's regenerator section, it will find an optimum temperature for growth. This highlights the need for frequent, effective cleaning and sanitization of the pasteurizer. Cleaning and sanitization become more problematic if there are pinhole leaks in the pasteurizer. There are no "silver bullets" offered by sanitizers, hygienic zoning, antimicrobials, or other methods.

Testing

There is no such thing as "zero" contamination when it comes to testing. Lot testing by itself is not adequate to establish that a product is free of a particular organism, as this would require testing the entire production lot with a perfect method. However, perfect methods do not exist, and testing the entirety of large industrial lots is impractical.

Imagine that 50 cells of Salmonella are present in a 500-pound (lb.) lot of product and that they are evenly distributed. This means that for every 10 lbs., there is a Salmonella cell. Then, imagine that 1 lb. of this product is tested. In the best scenario, there is a 1 in 10 chance of finding it. These odds become even more problematic when one considers that microbes are rarely distributed in a homogeneous manner in food.1

Microbial Counts are Not Absolute Numbers

Sporadic points of contamination, such as those which are likely to occur from the environment, are typically normally distributed (logarithmically speaking) when they occur. Thus, the use of arithmetic averages for microbiological contamination is ill-advised.6 In my experience, this is further supported by intra-laboratory variances of +/–0.5 log10 CFU on either side of the mean log10 CFU in quantitative data. Therefore, a microbial count of 100 CFU/g may actually be 30 CFU/g or 300 CFU/g. This knowledge should inform the establishment of microbiological criteria. A way to handle such variation is to establish criteria that account for it (e.g., set a specification that is lower than two or three standard deviations below the mean log10 CFU to minimize the chance of exceeding it).7

Bacterial Growth is Exponential Once They Have Adapted

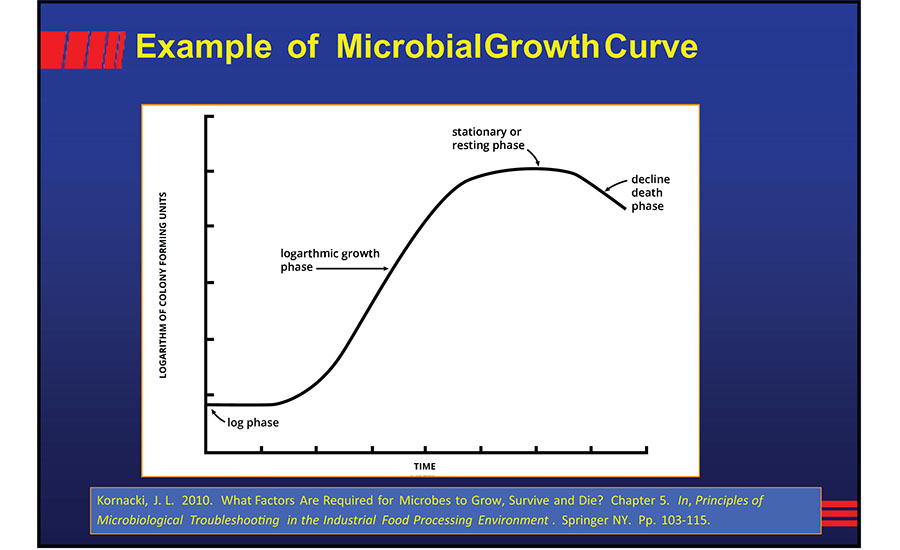

Microbial growth is a long-known phenomenon. Highly useful information can be gained from simply understanding a microbial growth curve (Figure 4).

In Figure 4, we see that there is a lag phase, a transition phase (positive accelerated growth phase) to the logarithmic or geometric growth phase, a "negative accelerated" growth phase, a stationary phase, and then a decline from the growth phase. The items in quotes were described by Robertson,6 although they were known much earlier. For example, research on the lag phase was reported in the late 18th century.9

It is well known that an Escherichia coli population, under ideal conditions, can double every 20 minutes once it is in the exponential phase of growth. This means that in 1 hour, there are eight times more of them. In 4 hours and 6 hours, there are 4,100 and 260,000 times more than the starting population, respectively. In 10 hours, from one E. coli cell, there should be just over a billion. There is abundant incentive to control the growth of such a pathogenic organism, and if this cannot be done expeditiously, then to ensure that they are in the lag phase. This understanding has implications for how long standing water is allowed to sit on a surface and how frequently cleaning and sanitation should take place.

Bacteria are Highly Adaptable; What Does Not Kill Them Makes Them Stronger

A colleague of mine once said, "Bacteria are smarter than we are, because they don't have a brain to worry about." Bacteria have just two functions: to grow and to survive. We have already shown how well they can grow, but their adaptability is incredible, as well. Any stress causes microbes to form biofilms, including nutrient deprivation (such as occurs after a water rinse), changes in pH, etc.10 This fact has implications for eradication vs. control of microorganisms in the factory environment, as biofilms provide profound protection for microbes.

For example, pasteurization of milk can destroy roughly 5.2 log10 of Listeria monocytogenes in 15 seconds at 71.7 °C (161 °F).11 However, for 90 percent probability of total Listeria monocytogenes biofilm destruction on stainless steel, a wet heat application at 70 °C (158°F) for 40 minutes is required.12 Similar data for the survival of various vegetative bacteria in liquid foods is found in the literature.13 If one assumes a population of 100,000 Listeria monocytogenes in a biofilm, then this suggests that Listeria monocytogenes are greater than approximately 160 times more heat-resistant in the biofilm than in fluid milk at the minimum pasteurization temperature and time of 71.7 °C (161 °F) for 15 seconds. This highlights the importance of rigorous cleaning and sanitation to remove and destroy biofilm-entrapped microorganisms.

Cleaning is the removal of soil from a surface, whereas sanitation, in the microbiological context, is the killing of microbial populations to acceptable levels. An unclean surface cannot be effectively sanitized. There is no substitute for careful, comprehensive, pre-operational visual cleaning inspections. The use of ATP testing of surfaces is helpful to verify the visual observations; however, testing surfaces for their aerobic plate count or other appropriate indicators provides for the verification of sanitation. Guidance on such testing is provided in the literature.14,15

Not Finding the Organism Does Not Mean it is Not There

Assumptions are often made about what conditions will destroy bacteria in a food production environment. However, eradication is impossible to prove. The phase, "the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence" comes to mind. One can never truly know whether an organism has been eradicated from a facility. Remember that bacteria are exceedingly small and therefore, hard to find. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Listeria draft guidance assumes that complete eradication of Listeria cannot occur in a food processing environment.16 The draft guidance document states on page 37, "…you should expect to detect the presence of Listeria spp. or L. monocytogenes on an occasional basis in environmental samples collected from your plant." The authors state that if Listeria testing of the environment is consistently negative, then environmental monitoring plans should be changed to ensure that harborage sites for this organism are not missed.

Since that which does not completely kill a population of microorganisms makes it stronger, multiple systems of control (or "hurdles") become important—and diligence is key.

Takeaway: Diligence is Essential

Since there is no "silver bullet" to completely eliminate microbiological contamination, diligence in the use of multiple approaches to microbiological control is essential. These approaches include:

- A good food safety plan with appropriate hazard analysis

- Process preventive controls

- Sanitation preventive controls

- Supply chain preventive controls with verification and validation (where possible)

- Appropriate hygienic zoning

- Environmental monitoring with documented corrective actions

- Good manufacturing practices

- Other controls, as necessary.

The control required for microbiological safety of food production brings to mind the phrase by John Philpot Curran, "The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance." We cannot let down our guard on controlling the microbiology of our facilities and our foods.

References

- Kornacki, J.L. Principles of Microbiological Troubleshooting in the Industrial Food Processing Environment. Springer, 2010. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4419-5518-0.

- Gabis, D.A. and R.E. Faust. "Controlling microbial growth in the food-processing environment." Food Technology 89 (December 1988): 81–82.

- Gurtler, J.B., M.P. Doyle, and J.L. Kornacki. "The microbiological safety of spices and low water activity foods: Correcting historic misassumptions." In The Microbiological Safety of Low Water Activity Foods and Spices. J.B. Gurtler, J.L. Kornacki, and M.P. Doyle (Eds.). Springer, 2014. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4939-2062-4.

- Chen, Y., et al. "Control of Salmonella in low-moisture foods II: Hygiene practices to minimize Salmonella contamination and growth." Food Protection Trends (July 2009): 435–445. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312993746_Control_of_Salmonella_in_low-moisture_foods_II_Hygiene_practices_to_minimize_Salmonella_contamination_and_growth.

- Kornacki, J.L. "Processing plant investigations: Practical approaches to determining sources of persistent bacterial strains in the industrial food processing environment." In The Microbiological Safety of Low Water Activity Foods and Spices. J.B. Gurtler, J.L. Kornacki, and M.P. Doyle (Eds.). Springer, 2014. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4939-2062-4.

- Robertson, A.H. "Averaging Bacterial Counts." Journal of Bacteriology 23, no. 2 (February 1932): 123–134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16559538/.

- Kornacki, J.L. "The Coming Storm in the Spice Industry, Part II: What the Industry Can Do." Food Safety Magazine February/March 2017. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/5174-the-coming-storm-in-the-spice-industry-part-ii-what-the-industry-can-do.

- Kornacki, J. "Chapter 5: What Factors are Required for Microbes to Grow, Survive, and Die?" In Principles of Microbiological Troubleshooting in the Industrial Food Processing Environment. Springer, 2010: 103–115. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4419-5518-0.

- Rolfe, M.D., C.J. Rice, S. Lucchini, et al. "Lag Phase Is a Distinct Growth Phase That Prepares Bacteria for Exponential Growth and Involves Transient Metal Accumulation." Journal of Bacteriology 194, no. 3 (February 2012): 686–701. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22139505/.

- Samrot, A., A.A. Mohamed, E. Faradjeva, et al. "Mechanisms and impact of biofilms and targeting of biofilms using bioactive compounds." Medicina 57, no. 8 (August 2021): 839. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8401077/.

- Mackey, B.M. and N. Bratchell."The heat resistance of Listeria monocytogenes." Letters in Applied Microbiology 9, no. 3 (September 1989): 89–94. https://academic.oup.com/lambio/article-abstract/9/3/89/6708988.

- Chemielewski, R.A.N. and J.F. Frank. "A predictive model for heat inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm on stainless steel." Journal of Food Protection 67, no. 12 (December 2004): 2712–2718. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15633676/.

- Sörqvist, S. "Heat resistance in liquids of Enterococcus spp., Listeria spp., Escherichia coli, Yersinia enterocolitica, Salmonella spp. and Campylobacterspp." Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 44, no. 1,2 (2003):1–19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14650540/.

- Moberg, L. and J.L. Kornacki. "Chapter 3: Microbiological monitoring of the food processing environment." In Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods. 5th Ed. F.P. Downes and K. Ito (Eds.). American Public Health Association, 2003. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/MBEF.0222.008.

- Lindsay, D., S.H. Flint, P. Venter, and J.L. Kornacki. 2024. "Chapter 14: Microbiological Tests for Air, Water, Containers, Equipment and the Dairy Processing Environment." In Standard Methods for the Examination of Dairy Products. 18th Ed. J.L. Kornacki, E. T. Ryser, and C. Mangione (Eds.). American Public Health Association, February 2024. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/book/10.2105/9780875533438.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Draft Guidance for Industry: Control of Listeria monocytogenes in Ready-To-Eat Foods. January 17, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/draft-guidance-industry-control-listeria-monocytogenes-ready-eat-foods.

Jeffrey L. Kornacki, Ph.D. is President and Senior Technical Director of Kornacki Microbiology Solutions Inc. He also serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Food Safety Magazine.