Digital Transformation of Foodservice: Potential Contributing Factors for Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

April 15, 2024

Digital Transformation of Foodservice: Potential Contributing Factors for Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

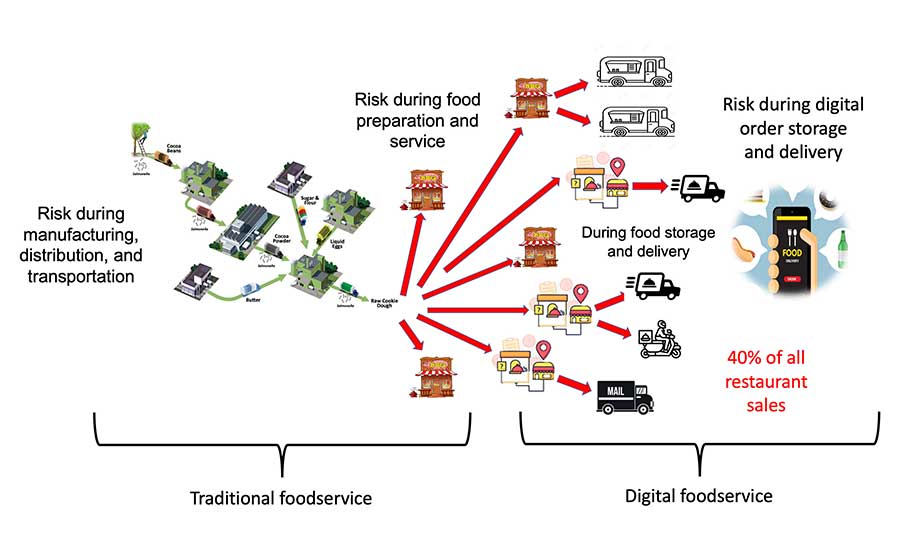

April 15, 2024Digital online ordering from retail foodservice establishments for prepared food delivery is a business model that has grown significantly in the U.S. since the historic shutdown of dine-in foodservice businesses due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many thought that once dine-in foodservice recovered, the digital ordering and delivery of foods would slow. However, digital online ordering now accounts for about 40 percent of total restaurant sales in the U.S.,1 and has grown 300 percent faster than dine-in sales since 2014. The U.S. is now the second-largest online food delivery market behind China, with an estimated $218 billion in revenue in 2022 generated by digital food ordering and delivery.2 By 2027, the market is forecast to expand even further, edging close to the $500-billion mark, as new meal delivery segments continue their upward climb in the U.S.

The ordering of foods from restaurants for delivery is not new, of course, but it has always been limited by several factors:

- Most foodservice businesses offered delivery only via their own employees (vs. using food delivery companies) and dayparts, limiting the number of foods prepared each day

- Most foodservice businesses offered delivery to customers only via a phone call to the business

- Delivery was advertised in the phone book, on the company website, or perhaps at the point of sale in the facility

- Customers associated delivery with certain menu items or food concepts (e.g., pizza or Chinese food)

- Very few full service restaurant (FSR) or quick service (QSR) restaurant businesses offered menu items for sale outside of their drive-thru/pickup offerings.

Delivery orders were viewed by most restaurant operators as an extra table for the restaurant, with service to the customer by a driver instead of a waiter. Using delivery was a means to increase sales volume, using the same kitchen.3 With the introduction of the smartphone and mobile apps to help consumers find information via the internet, and for foodservice business to market their products, the foodservice industry mobile app was just the next iteration of convenience to get food. The first online food ordering service, World Wide Waiter (now known as Waiter.com), was founded in 1995.4 The site originally serviced only northern California, but later expanded to several additional cities in the U.S. By the late 2000s, major pizza chains had created their own mobile applications and started doing 20–30 percent of their business online.5

Chipotle, the Mexican cuisine chain, was a pioneer in mobile app ordering. The company launched its first app in 20096 to allow guests to order ahead of time and skip the long make lines required to select ingredients to order meals in the restaurants. Customers could just pick up and pay for their order to dine in or take out. In 2014, Taco Bell was the first foodservice brand to unveil an advanced mobile app7 that let customers order and pay for their orders on their smartphones, and then walk or drive in and pick up their food. However, delivery of food was not an option on either restaurant brand's app. To market the new app, all of Taco Bell's social media platforms—including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr—went "dark," telling customers that the new way to get food from Taco Bell was by their app (using the hashtag #onlyintheapp as a means to spread the word on social media). This national marketing strategy increased sales to each individual local restaurant across the U.S.

Once digital ordering via food delivery companies like DoorDash (started in 2013) and Uber Eats (started in 2014) became available, almost all local foodservice businesses—not just the restaurant chains—became available for online ordering and delivery.

By 2015, online ordering began overtaking phone ordering,8 exponentially growing the digital delivery business model in the foodservice industry. By 2021, DoorDash had 390,000 partnered restaurants9 and grocery markets on its platform. The growth of technology companies enabling ordering and delivery of food from restaurants continues to grow today. Google now enables customers to directly order food from foodservice businesses via Google Search, Google Maps, or the Google Assistant app.10

Physical to Digital Lines

At present, there seems to be no limit to the number of customers who could order food from a single restaurant; obviously, this provides a significant means for a foodservice business to grow its sales. This also significantly alters the foodservice business model. Online ordering is becoming big business for top QSR chains.11 McDonald's reported $7 billion in global digital sales in its top six markets in 2022, while Chipotle had over $3 billion in digital sales. Yum! Brands' global digital sales were over $24 billion in 2022.

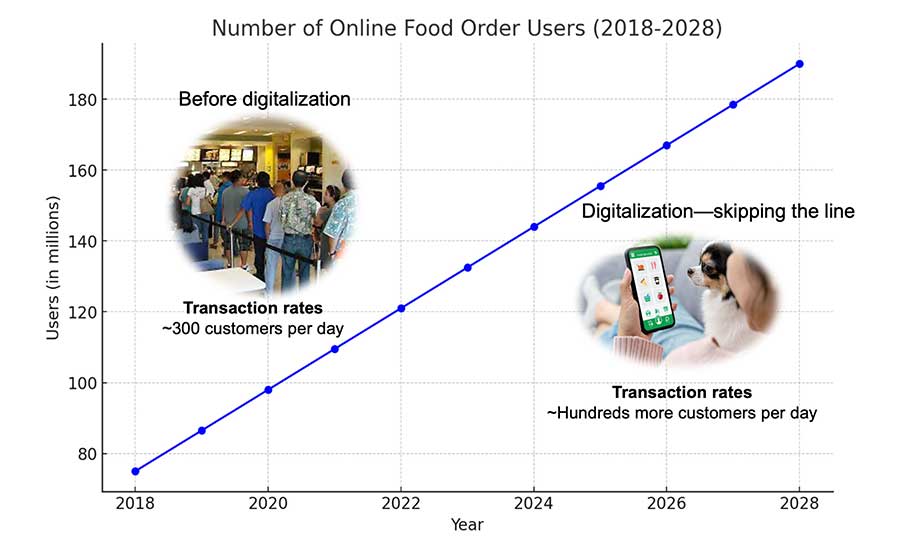

Before digital online ordering, you had to wait in line or in your car (or sit at a table) to order and receive your food, and the average transaction rate (number of menu items prepared per day) that the average QSR kitchen was expected to prepare could be approximately 300 orders per day.12 However, after the digitalization of foodservice ordering (Figure 1), these transaction rates increased exponentially.

This augmented volume of sales that must be prepared in the same kitchen (for most of the foodservice industry) can often be too large to be accommodated by the labor needed and kitchen space/equipment design, leading to quality and delivery issues impacted by the large number of virtual customers that can order from any one kitchen via multiple delivery service apps. In a recent survey,11 digital ordering has made operations more complex at 82 percent of QSR chains compared to 31 percent at FSR chains. Eighty-five percent of QSR chains said they are having a hard time meeting digital ordering expectations, compared to 59 percent of FSR chains. The growth of the FSR and QRS industry promises to increase the volume of online delivery just by the growing number of new restaurants. McDonald's plans for 50,000 total restaurants by 2027,13 Starbucks is working to have 55,000 cafes by 2030,14 and Chipotle is planning 7,000 restaurants, doubling its current number.15 In 2023, Yum! Brands opened more restaurants in a single calendar year than any other restaurant company on record, and is expected to reach over 60,000 restaurants in 2024.16

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

Some evidence suggests that customers are being impacted by the digital ordering pressure on foodservice kitchens. In a 2022 study17 of customers who use online food ordering, the leading frustration associated with customers' online food delivery was long delivery time (more than a third of respondents listed this as an issue), incorrect and incomplete orders, and food not arriving at the correct temperature. In a survey of over 1,000 customers in the U.S.:18

- 51 percent of Americans blamed the delivering company or restaurant the most for a late delivery, rather than the delivery service or driver

- 54 percent of Americans suspected their food delivery driver of eating their food or drinking their drink prior to delivery.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to manage the exponential volume of sales that a single foodservice kitchen can prepare to meet digital mobile ordering demand, a number of ghost kitchen businesses were developed and/or expanded.19 These delivery-only foodservice kitchens (where there is no dine-in service) may also include mobile kitchens designed for pickup only (food trucks or trailers where food preparation occurs and delivery service pickup is completed). This business model is expected to grow20 in the U.S. from $43.1 billion in sales in 2019 to $157 billion by 2030.21

As access to a large number of customers via digital marketing continues to grow, some ghost kitchen businesses have also evolved out of social media influencers or directly by social media technology companies themselves. Some social media influencers also offer branded recipes to existing restaurants for the opportunity to prepare and sell specific branded menu items from their existing kitchens, which brings millions of potential customers. One ghost kitchen startup specializes in linking pre-existing restaurant kitchens with new, virtual restaurant concepts where the existing restaurant kitchen can make food for another brand while maintaining its own establishment. This has resulted in the growth of several social media-launched ghost kitchen businesses22 that bring thousands of digital customers—all of which can overwhelm a foodservice establishment designed for different menus and a lower volume of sales.

A new, non-traditional, mail-order delivery concept has developed where participating restaurants can receive orders via an e-commerce technology company's website/app, and then ship the food directly to the customer via next-day delivery companies like UPS and FedEx. The e-commerce business facilitates the digital ordering marketplace for thousands of restaurants and food retail businesses to sell specific menu items to customers (after cooling or freezing the foods and packaging them properly) anywhere in the U.S. that delivery companies deliver packages and mail. For example, Goldbelly,24 one of the most successful e-commerce businesses, has over 1,000 participating retail and foodservice sales partners that sell several foods packaged in containers with cold packs or dry ice and shipped directly to a customer's home. The customer can choose when the order ships and is notified when the package is delivered. This business model can significantly increase the volume of transactions within a food business kitchen that is not designed for this volume of food preparation, in addition to having the systems to ensure that prepared foods are cooled down safety and/or frozen and packaged safely before shipping via a delivery business that is not designed for the sanitary transportation of refrigerated/frozen foods.

The Potential for Greater Risk of Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

Foodservice establishments in the U.S. continue to cause the greatest number of foodborne illness outbreaks every year, among all causes of foodborne outbreaks. Before the pandemic, as reported by CDC in 2017,24 60 percent of all foodborne illness outbreaks in the U.S. were caused by foodservice establishments. Today, the most current data (2021)25 on the number of foodborne illness outbreaks caused per year by foodservice establishments shows that nothing has changed, at 64 percent. According to this data, there were 307 outbreaks (out of 479), 3,526 illnesses, 190 hospitalizations, and 5 deaths caused by foodservice establishments in one year.

CDC does not currently track or report foodborne illness outbreaks caused by digital online orders and delivery from foodservice establishments; therefore, the surveillance of foodborne illnesses from online food delivery is not well established. Reports of outbreaks associated with online delivery of foods have surfaced. In 2020, the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention in China26 reported an outbreak of 10 cases of Salmonella enterica infection, identified by whole genome sequencing (WGS) and traced to food ordered online. The Shenzhen CDC suggested that food delivery platforms were a new mode of foodborne illness transmission. Whenever existing hazards and their probability have significantly increased due to the volume of foods prepared in a single kitchen (Figure 2), the risk of foodborne illnesses and outbreaks from that kitchen is likely to increase, as well. A strong probability exists that this business model may contribute to, and perhaps increase, the burden of foodborne illness caused by foodservice establishments in the U.S.

Potential Contributing Factors to Foodborne Illness Outbreaks

We do not yet understand the total scope of the risk of the digitalization of foodservice, but we can list potential contributing factors to this risk and prepare for them now. These factors include those that are known to be contributing factors for foodborne illness outbreaks28 and illnesses from traditional foodservice establishments, all of which could be exponentially increased due to the volume of sales pressure on a typical foodservice kitchen.

The three types of contributing factors are:

- Contamination: Pathogens and other hazards like allergens get into food

- Proliferation: Pathogens that are already in food multiply

- Survival: Pathogens survive a process to kill or reduce them.

These contributing factors are likely to increase due to the volume of digital orders associated with foodservice food preparation. These factors may also occur during post-preparation, such as during holding (i.e., keeping food hot or cold to prevent growth of pathogens, and/or cooling it down properly), handling (i.e., preventing contamination of the packaging due to sanitation and personal hygiene issues), transporting (i.e., keeping the food hot or cold and tamper-resistant), and delivering the food to a customer (i.e., ensuring the customer receives the food in a timely manner and is aware of the ingredients to avoid declared allergens). As many customers are ordering from a mobile app or website, they may also be at a higher risk for allergens due to the lack of avoidance messaging that is normally part of the in-restaurant and/or brand website ordering process.

In the Kitchen

Multiple hazards can be associated with one or more food preparation steps for just one food item in a foodservice establishment. Examples include Salmonella Typhi in raw chicken and E. coli O157 on fresh produce. In response to these hazards, many foodservice businesses develop specific food safety specifications, known as standard operation procedures (SOPs), based on the hazards associated with the preparation of their menu items and how to best control them. For example, a restaurant brand that prepares and sells chicken sandwiches may have requirements for the safe handling of raw chicken (e.g., wearing color-coded gloves28) and washing produce using a produce wash agent29 to reduce the risk of cross-contamination. Employees must be trained on these requirements, and managers must be trained to monitor controls to ensure compliance. These tasks are often based on the number of employees needed (labor) and the space available to prepare food safely under sanitary conditions. However, if the kitchen normally prepares ten of these menu items per hour, but digital orders increase that to 100 per hour (along with other menu items needing to be prepared in greater quantities), then the required specifications and monitoring may not be feasible. Likewise, the miscommunication or failure to convey special instructions to food handlers preparing the foods can lead to food safety issues, such as the incorrect handling of allergen-free or dietary-specific meals.

Best Practices

A Process HACCP plan and Food Safety Management System (FSMS)30 is the best means to identify the different hazards and their risk of happening in the kitchen to ensure that the proper controls are in place and monitored by managers. Each recipe or procedure that involves receiving, storing, and preparing ingredients, and then serving each prepared menu item, is analyzed to determine the potential hazards at each process. Next, the controls needed to prevent each hazard are defined. These hazard controls at each food preparation process can be either a Critical Control Point (CCP) (e.g., cooking the chicken to 165 °F/74 °C) or a Prerequisite Control Point (e.g., ensuring that areas where raw chicken is prepared are properly cleaned and sanitized, and ensuring that employees wash hands and wear gloves properly after handling raw chicken).

This process approach to HACCP is recommended by the FDA Food Code31 (see Annex 4) to assist foodservice establishments in achieving Active Managerial Control of food safety risk. It also includes the need for a Sanitation Prerequisite Program32 to define and control potential hazards associated with ingredients sourcing, cleaning and sanitation, employee health, hand hygiene, and other common food processes that occur in a foodservice establishment—all of which would be expected to increase with an increasing volume of orders and labor needs. Since some kitchens (e.g., ghost kitchens) prepare multiple menus from different foodservice brands, the development of a Process HACCP plan is even more important to ensure food safety.

Additional best practices include the following:

- Develop a Process HACCP plan for all menu items prepared in the kitchen, especially the most commonly ordered menu items for delivery. Use the plan to develop an FSMS, and use the system to monitor the control of all hazards.

- Ensure that specific ingredients required by each recipe are used only for that menu item and not substituted.

- Train employees on the proper food preparation of each menu item, including the hazard controls for each.

- If the volume of digital sales is large, add another "digital make line" for food preparation of digital orders for delivery. Chipotle developed digital make lines prior to the pandemic to ensure food safety and throughput of food preparation for this purpose.33

- Develop specific food safety specifications for any ghost kitchen, especially those that prepare different QSR and FSR brand menus in the same kitchens.

New Kitchen Technologies to Reduce Risk During Food Prep Needs

New technologies being tested and implemented in the foodservice industry may be able to reduce food preparation risk by enabling a larger volume of menu items to be prepared more safely in a single kitchen with less contamination. In one example, robotics may be able to produce over 300 menu items per hour34 to help meet demand. Both Chipotle35 and Sweetgreen36 have tested new robotic technologies that automate some aspects of the preparation steps with ready-to-eat ingredients (e.g., burrito bowls or salads). Fully robotic food preparation37 is also being developed for this need.

During Packaging, Holding, and Delivery

The majority of foods prepared at restaurants and served to customers for pickup or delivery (or dine-in within a QSR or FSR) are packaged with single-use wrappers/cartons/containers intended to facilitate handling the foods for immediate consumption. This single-use packaging is not intended for holding hot or cold foods outside of temperature control devices, storing, or reheating the foods. Maintaining the correct temperature for hot and cold items throughout the foodservice location holding and delivery process to prevent proliferation is a significant risk because of this type of packaging. The lack of standardized equipment for all delivery personnel and varying transit times can lead to food entering the "danger zone" (from 41–135 °F/5–57 °C), where pathogens can rapidly multiply (doubling in 20 minutes or making toxins within 30 minutes), even within the time food is held in the foodservice establishment, picked up, and then delivered to a customer.

These foods are often delivered with very little outer packaging to protect them from contamination and spillage, compromising the wrapping and affecting quality. The risk of tampering with the food, most likely related to the delivery person opening the wrapping to eat some of the food,38 or worse, putting something into the food to cause illness or injury to a customer, is high due to the nature of food packaging for delivery. The balance between sustainable materials and the need for more robust, insulated, tamper-preventive outer packaging poses a significant challenge.

Another food safety concern during food delivery is contaminated environmental surfaces that could play a critical role in the indirect (secondary) transmission of pathogens. For example, the virus that causes stomach flu, norovirus, can survive on surfaces for many days, with even greater persistence at cold temperatures. Norovirus can be transmitted not just by a food handler during food preparation, but also by contamination of items reused to carry foods, including reusable food storage and delivery equipment and bags.39

Best Practices

The foodservice business is responsible for the safety of its food delivered to a customer, and this responsibility does not stop after the food leaves the foodservice facility. The business should:

- Choose to hold foods prepared for delivery by temperature, not time, and hold hot or cold (or ambient) according to food safety requirements, until the food is picked up for delivery. This would improve the quality of the foods upon delivery, thereby enhancing customer experience and value, and ensuring food safety due to delayed pickup or delivery.

- Ensure that the delivery service uses insulated delivery bags,40 which are offered by each third-party delivery service to keep the foods hot or cold before delivery.

- Ensure that the third-party delivery drivers follow the guidelines (e.g., see DoorDash food safety guidelines41) that include inspection of the delivery vehicle to ensure cleanliness, ensuring drivers are using proper disinfection protocols, confirming drivers are trained on proper food handling risks (keeping hot foods hot and cold foods cold) and establishing personal hygiene expectations and wellness screenings for drivers.

- Ensure that the outer packaging bags or containers are secure and are tamper-evident, while also being sustainable and capable of maintaining food integrity.

Additional recommendations and best practices for third-party delivery service are noted in the Conference for Food Protection guidance for the food industry.42

Delivering Food via Mail Order

During a 2022 Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) Annual Meeting and Science Symposium (reviewed by Food Safety Magazine43), experts addressed the food safety concerns and possible solutions associated with meats ordered online, based on a joint research project funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.44 The study evaluated meat, poultry, seafood, and game products that were ordered online and delivered by FedEx, UPS, and USPS. The researchers found that, in many cases, the packaging of food products ordered online was inadequate, and vendors often provided incorrect food safety information both on food packaging and on their websites. Delivered packages exhibited issues with improper packaging material, improper use of coolants, and unsuitable delivery temperatures; nearly half (47 percent) of the studied products arrived with surface temperatures above 41 °F/5 °C.

As discussed above, all foods normally made in a foodservice business are prepared, sold, and served for immediate consumption. Restaurant foods are packaged only for handling, not for properly holding foods. FDA has specific rules about packaging of foods for both food manufacturers and restaurants,45 and the FDA Food Code outlines the risks and recommendations for packaging foods in restaurants if not intended for immediate consumption.46 Thus, most of these foods are not properly packaged for shipping and delivery times of 24–48 hours after they have been prepared and cooled or frozen. If the outer packaging does not keep the foods below 41 °F/5 °C or frozen, then proliferation of pathogens is likely, and the degree of pathogen growth and/or toxin production increases based on the time above 41 °F/5 °C.

Some menu items are not designed for cooling down and shipping under conditions where there is likely temperature abuse—i.e., where they may not be held under 41 °F/5 °C at all times. Some foods, like smoked fish, are required to be held at 38 °F/3.3 °C during storage and shipping,47 due to possible growth of bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes or bacterial toxins that can occur at low temperatures. The risk can increase based on the type of packaging used (e.g., reduced oxygen packaging) if the ingredients/foods (e.g., sous vide) likely will have spore-forming bacteria that make toxins. Finally, the current express mail business is not designed for the sanitary transportation of foods that can also ensure temperature control. The vehicles are not equipped to keep packaged foods cold or frozen (when packed with cool or frozen packs) under extreme temperature conditions. Packages of food are regularly dropped at customers' doors, not signed for, nor immediately placed into cold/frozen storage. If customers are not home when the foods are delivered, then the foods sit outside and the risk of bacterial proliferation increases.

Best Practices

Foods delivered by mail order have increased risk due to packaging issues and longer times in transportation and delivery. Therefore, the foodservice establishments that prepares foods for mail order should ensure these controls:

- Ensure that all packaging used by the restaurant that comes into contact with the foods meets FDA requirements

- Ensure that the restaurant is designed and equipped to prepare menu items for cooling down foods properly prior to packaging and shipping

- Recommend that the cool-down process is verified and documented for all foods that will be shipped

- Do not use reduced oxygen packaging for preparation and shipping of any mail-order products

- Ensure that the menu items selected to ship do not contain hazards that will be more probable during shipping if cold/frozen temperature abuse or fluctuations occur

- Review menu items and ingredients for the likely presence of pathogens (according to FDA descriptions)

- Consider cool-down and cold shipping of all cheeses, regardless of type

- Ensure that packaging is designed to keep packaged foods cold or frozen up to the time of delivery (and in all seasons)

- Provide guidance to the customer on how to hold the foods if they do not consume them immediately48

- Perform temperature surveillance of food deliveries to validate that the packaging keeps the foods cold/frozen

- Provide a time stamp by the restaurant that shows the customer when the food was cooled below 41°F/5 °C and packaged

- Consider a "sign for receipt" process to document when foods are delivered and accepted by customers

- Ensure the carrier has directions if customers are not at home, or provide a text to the customer to alert when the delivery has been made

- Provide guidance not to consume the foods if they are not at the proper temperature upon arrival

- Develop a recall system to enable a notification to consumers of any products that have been recalled or found to have food safety issues.

Additional resources for the can be found in the Conference for Food Protection's Guidance Document for Mail Order Food Companies.49

Takeaway

The digital transformation of foodservice has provided the industry with a significant boost in sales beyond the traditional dine-in, pickup, or drive-thru sales that existed before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, with increased sales driving business beyond what the existing foodservice kitchen was designed to produce, comes more risk. The CDC,50 FDA,51 and USDA48 provide consumer awareness messaging on the risk associated with meal delivery; however, there are no FDA or USDA regulations and little surveillance on the actual risk. For these reasons, it is important to identify the potential contributing factors of foodborne illness outbreaks in foodservice establishments and be prepared to prevent them.

The integration of technology to meet higher demands on the foodservice business due to the large number of digital orders also offers significant opportunities to enhance food safety. The commitment of the foodservice industry to adopt best practices for prevention is crucial in safeguarding consumer safety while maintaining the convenience and efficiency that define the modern food delivery experience. From tracking where foods are from and which customers received them—something that was not feasible before digital ordering for delivery—these innovations not only address current challenges, but also pave the way for a future where food delivery is synonymous with safety and reliability.

References

- Lempert, P. "The Future Of Food Delivery Depends On Human Emotions: Not Speed." Forbes. February 17, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/phillempert/2023/02/17/the-future-of-food-delivery-depends-on-human-emotions-not-speed/?sh=34faea05c8c2.

- Beyrouthy, L. "Online food delivery in the U.S.—Statistics & facts." Statista. December 18, 2023. https://www.statista.com/topics/3294/online-food-delivery-services-in-the-us/#topicOverview.

- Ahuja, K., V. Chandra, V. Lord, and C. Peens. "Ordering in: The rapid evolution of food delivery." September 21, 2021. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/ordering-in-the-rapid-evolution-of-food-delivery.

- Corcoran, D. "How to Make Lunch an Adventure." The New York Times. December 13, 2000. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/tech/00/12/biztech/technology/13corc.html.

- Bryson York, E. "Why Pizza Giants Want Customers to Click, Not Call, For Delivery." AdAge. April 20, 2009. https://adage.com/article/digital/pizza-giants-customers-click-call-delivery/136087.

- "Chipotle to Launch New Mobile Apps, Providing Multiple Guest Benefits." Restaurant Technology News. September 2017. https://restauranttechnologynews.com/2017/09/242/#:~:text=Chipotle%2C%20the%20Mexican%20cuisine%20chain,skip%20the%20line%20upon%20arrival.

- Horovitz, B. "Taco Bell unveils mobile ordering." USA Today. October 28, 2014. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2014/10/28/taco-bell-outback-starbucks-restaurants-fast-food-casual-dining-technologies/17842845/.

- Shanker, D. "Online food delivery ordering is about to overtake phone ordering in the US." Quartz. July 14, 2015. https://qz.com/452609/online-food-delivery-ordering-is-about-to-overtake-phone-ordering-in-the-us.

- Curry, D. "DoorDash Revenue and Usage Statistics (2024)." January 8, 2024. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/doordash-statistics/.

- "Google Integrates Food Ordering Into Search, Maps." PYMNTS. May 23, 2019. https://www.pymnts.com/google/2019/restaurant-mobile-ordering-food-delivery/.

- Littman, J. "QSRs expect 51% of tasks will be automated by 2025." Restaurant Dive. March 29, 2023. https://www.restaurantdive.com/news/72-percent-restaurant-operators-struggling-to-meet-digital-ordering-demands/646203/.

- Hoeksema, A. "4 Financial Projection Models for the 4 Restaurant Styles." ProjectionHub. June 6, 2017. https://blog.projectionhub.com/4-financial-projection-models-for-the-4-restaurant-styles/.

- Klein, D. "McDonald's Eyes 50,000 Restaurants by 2027 as Digital Explodes Globally." QSR Magazine. December 6, 2023. https://www.qsrmagazine.com/operations/fast-food/mcdonalds-eyes-50000-restaurants-by-2027-as-digital-explodes-globally/.

- Coley, B. "Starbucks Wants 55,000 Shops, and It Will Cut $3 Billion Along The Way." QSR Magazine. November 3, 2023. https://www.qsrmagazine.com/news/starbucks-wants-55000-shops-and-it-will-cut-3-billion-along-the-way/.

- Klein, D. "Chipotle Speeds Toward Even Greater Heights." QSR Magazine. February 9, 2024. https://www.qsrmagazine.com/story/chipotle-speeds-toward-even-greater-heights/.

- Coley, B. "Yum! is Building Restaurants ay an Unprecedented Pace." QSR Magazine. February 7, 2024. https://www.qsrmagazine.com/story/yum-is-building-restaurants-at-an-unprecedented-pace/.

- Statista Research Department. "Leading frustrations customers have with online food delivery worldwide in 2022." Statista. August 15, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1366234/online-food-delivery-top-frustrations-worldwide/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20the%20leading%20frustration,rounded%20out%20the%20top%20three.

- Reinblatt, H. "How Spoiled Are Consumers With On-Demand Delivery? [Study]." Circuit. April 29, 2022. https://getcircuit.com/route-planner/blog/expectations-of-delivery.

- Murphy, T. "The Growth of Ghost Kitchens, and What Makes Them Work." QSR Magazine. February 17, 2022. https://www.qsrmagazine.com/operations/outside-insights/growth-ghost-kitchens-and-what-makes-them-work/.

- Smith, S. "A look inside the $43 billion ghost kitchen industry." National Retail Federation. October 13, 2021. https://nrf.com/blog/look-inside-43-billion-ghost-kitchen-industry.

- Coherent Market Insights. "Ghost Kitchen Market to reach $157.26 billion by 2030 globally, at a CAGR of 12%, says Coherent Market Insights." Globe Newswire. July 28, 2023. https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2023/07/28/2713295/0/en/Ghost-Kitchen-Market-to-reach-157-26-billion-by-2030-Globally-at-a-CAGR-of-12-says-Coherent-Market-Insights.html.

- Guszkowski, J. "MrBeast Burger hints at more physical locations after record-breaking debut." Restaurant Business. September 16, 2022. https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/technology/mrbeast-burger-hints-more-physical-locations-after-record-breaking-debut.

- Goldbelly. https://www.goldbelly.com/.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks United States, 2017: Annual Report." 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/fdoss/pdf/2017_FoodBorneOutbreaks_508.pdf.

- CDC. "National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS)." https://wwwn.cdc.gov/norsdashboard/.

- Jiang, M., F. Zhu, C. Yang, Y. Deng, P.S.L. Kwan, Y. Li, Y. Lin, Y. Qiu, X. Shi, H. Chen, Y. Cui, and Q. Hu. "Whole-Genome Analysis of Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteriditis Isolates in Outbreak Linked to Online Food Delivery, Shenzhen, China, 2018." Emerging Infectious Diseases 26, no. 4 (April 2020). https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/4/19-1446_article.

- CDC. "What Are Contributing Factors?" March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/nears/what-are-contributing-factors.htm.

- King, H. and B. Michaels. "The Need for a Glove-Use Management System in Retail Foodservice." Food Safety Magazine. June 18, 2019. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/6258-the-need-for-a-glove-use-management-system-in-retail-foodservice.

- Moorman, E. and H. King. "Is It Time for a 'Kill Step' for Pathogens on Produce at Retail?" Food Safety Magazine. December 1, 2016. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/5104-is-it-time-for-a-e2809ckill-stepe2809d-for-pathogens-on-produce-at-retail.

- King, H. Food Safety Management Systems. Springer: 2020. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-44735-9.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Food Code 2017. Current as of March 7, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/fda-food-code/food-code-2017.

- King, H. "Sanitation Prerequisite Programs as a Necessary Component of FSMS for Foodservice Establishments." Food Safety Magazine October/November 2022. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/8055-sanitation-prerequisite-programs-as-a-necessary-component-of-fsms-for-foodservice-establishments.

- Lalley, H. "Chipotle's digital make lines are generating the AUVs of a standalone restaurant." Restaurant Business Online. July 23, 2020. https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/operations/chipotles-digital-make-lines-are-generating-auvs-standalone-restaurant.

- "Automated Makeline prepares 350 meals per hour with highest order accuracy." BECKHOFF. May 4, 2022. https://www.beckhoff.com/en-us/company/news/automated-makeline-prepares-350-meals-per-hour-with-highest-order-accuracy.html.

- Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. "Chipotle Teams Up with Hyphen to Begin Testing New Digital Makeline." October 3, 2023. https://newsroom.chipotle.com/2023-10-03-CHIPOTLE-TEAMS-UP-WITH-HYPHEN-TO-BEGIN-TESTING-NEW-DIGITAL-MAKELINE.

- Jennings, L. "Sweetgreen's robotic Infinite Kitchen is finally open." Restaurant Business. May 10, 2023. https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/technology/sweetgreens-robotic-infinite-kitchen-finally-open.

- Kitchen Robotics. "Discover the Power of Automation with a Commercial Robotic Kitchen." https://k-robo.com/.

- Matias, D. "1 in 4 Food Delivery Drivers Admit to Eating Your Food." NPR. July 30, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/07/30/746600105/1-in-4-food-delivery-drivers-admit-to-eating-your-food.

- Repp, K.K. and W.E. Keene. "A point-source norovirus outbreak caused by exposure to fomites." The Journal of Infectious Diseases 205, no. 11 (May 2012): 1639–1641. https://europepmc.org/article/med/22573873.

- Uber Eats. "Bag Collection." https://ubereatsshop.com/collections/bag-collection.

- DoorDash. "What are DoorDash's food safety handling requirements?" https://help.doordash.com/dashers/s/article/What-are-DoorDash-s-food-safety-handling-requirements?language=en_US.

- Conference for Food Protection (CFP). Guidance Document for Direct-to-Consumer and Third-Party Delivery Food Service Delivery. http://www.foodprotect.org/guides-documents/guidance-document-for-direct-to-consumer-and-third-party-delivery-service-food-delivery/.

- Henderson, B. "Food Safety Concerns of E-Commerce, Ghost Kitchens, Delivery." Food Safety Magazine. June 22, 2022. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/7840-food-safety-concerns-of-e-commerce-ghost-kitchens-delivery.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Research, Education, and Economics Information System (REEIS). "Identifying Food Safety Risk Factors and Educational Strategies for Consumers Purchasing Seafood and Meat Products Online." August 31, 2015 (project end date). https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/0226297-identifying-food-safety-risk-factors-and-educational-strategies-for-consumers-purchasing-seafood-and-meat-products-online.html.

- FDA. "Food Ingredients & Packaging." Current as of July 6, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging.

- FDA. "Summary of Changes in the 2022 FDA Food Code." Current as of January 19, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/fda-food-code/summary-changes-2022-fda-food-code.

- Gublo, F. "Commercial smoked fish need to be properly stored." Michigan State University Extension. December 9, 2016. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/commercial_smoked_fish_need_to_be_properly_stored#:~:text=The%20key%20temperature%20for%20smoked,warehousing%20and%20retail%20display%20cases.

- USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). "Mail Order Food Safety." March 30, 2015. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/mail-order-food-safety.

- CFP. Guidance for Mail Order Food Companies. http://www.foodprotect.org/guides-documents/guidance-for-mail-order-food-establishments/.

- CDC. "Food Delivery Safety." October 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/communication/food-safety-meal-kits.html.

- FDA. "5 Red Flags to Look For When Shopping for Meal Kits." Current as of October 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/5-red-flags-look-when-shopping-meal-kits.

Hal King, Ph.D. is Managing Partner of Active Food Safety LLC and a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Food Safety Magazine. He can be reached at halking@activefoodsafety.com.