In Dry Environments, Wet Sanitation Isn't the Answer—It's the Issue

Despite the appeal of water as a "more thorough" sanitation method, moisture behaves very differently in dry facilities than may be expected

Applying wet sanitation in dry environments often increases risk. Food processors need a balanced understanding of these risks and their desired cleaning outcomes. Specifically, it is important for processors to understand the impact of different sanitation practices and how those impacts are driven by hygienic design challenges in their facilities.

Wet vs. Dry Cleaning in Low-Moisture Environments

In low-moisture food facilities, few decisions generate as much debate as whether to introduce wet sanitation steps. A common misconception that continues to drive the debate is that, after dry cleaning, if the results appear to be anything less than perfect—especially on equipment that is hard to clean or has known harborage points—the solution must be to add water. In practice, this assumption often leads facilities toward higher-risk conditions and more complicated sanitation outcomes.

The reality is that when a surface is inherently hard to clean because of hygienic design challenges, adding water rarely improves the situation. In fact, adding water typically makes it worse. Environmental sanitation programs do not result in a sterile environment, devoid of all viable microorganisms. Rather, some microbial cells will persist after either wet or dry sanitation. Consequently, the introduction of water into the environment enhances the ability of those remaining microbes to grow.

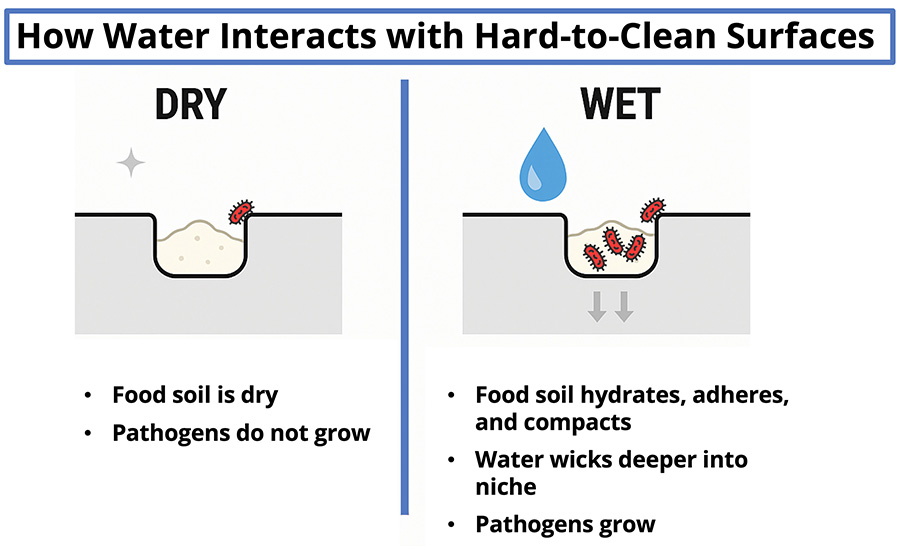

Moreover, the use of water does not overcome poor hygienic design. Water can, however, drive food soils and microbes further into the same inaccessible niches that are challenges during dry sanitation. When water is used in sanitation, the one resource that limits the growth of environmental microbes is introduced, and the dry food residues are no longer below the water activity that inhibits microbial growth—they are rehydrated into conditions that support microbial growth.

It is unrealistic to assume that all food residues will always be completely removed from complex or poorly designed equipment, even if the surface appears visibly clean.1 When low-level soil remains on surfaces, adding water transforms an otherwise microbiologically static condition into one where growth and consequent cross-contamination risk increases. Water creates the perfect storm. It changes the physicochemical properties of soils, making them harder to remove, and enables pathogen growth.

Although most dry facilities strive to minimize water use, there are common reasons why wet sanitation is still sometimes used. This choice to use a wet wash is predominantly driven by allergen changeovers or lot segregation (i.e., "sanitation breaks"). Also, many facilities face regulatory or customer expectations that erroneously push operators toward wet sanitation even when their equipment is designed for dry processing. These pressures are real, and they also create risk–risk tradeoffs because controlling allergens via wet sanitation may inadvertently increase the risk from microbial hazards.

Risk-based sanitation decisions must be made within the reality of the environment you already have. Legacy equipment is common in dry facilities, and even newly designed systems inevitably contain some degree of hygienic design challenge. The plan should not be to expect perfect (e.g., smooth, flat) surfaces, but to understand where the gaps are and how water interacts with those vulnerabilities, and to develop a strategy for the sanitation method that reduces—not amplifies—those risks (Figure 1). By recognizing the actual constraints of the facility, processors can better balance competing priorities and make decisions that genuinely strengthen food safety.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

What Makes a Surface Hard to Clean

Hard-to-clean niches arise from a predictable set of factors: limited access, tight geometries, and rough surfaces that are shielded from the mechanical action necessary for cleaning. However, these characteristics limit sanitation efficacy regardless of the method used. A vacuum nozzle cannot reach inside a poorly welded seam any more easily than a low-pressure hose can rinse it clean. A rotary valve is difficult to clean dry, but equally difficult to clean wet. Mechanical action is inherently limited when surfaces are poorly accessible (Figure 2), which is why switching from dry to wet cleaning rarely solves the problem.

FIGURE 2. Residual dairy powder on a butterfly valve (A). Sanitation procedures differ between dry cleaning (B) and wet cleaning (C). However, microbial risk will be enhanced with the introduction of water for any residual dairy powder in hard-to-clean niches on this complex surface (Credit: Cornell Dry Sanitation Advisory Council)

Hygienic design standards have played a role in optimizing dry processing environments because they help define the physical conditions that shape surface construction. In dry facilities, equipment and infrastructure should be designed so that soil residues cannot lodge, moisture cannot collect, and surfaces remain accessible for dry cleaning.2

Principles emphasized in the 2009 Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA, now the Consumer Brands Association) guidance include eliminating niches and preventing liquid collection. As the GMA guidance noted, keeping the environment dry is "critically important in preventing Salmonella contamination"3 in dry products, and preventing water ingress is one of the primary goals of hygienic design. These standards help ensure that if Salmonella or other microorganisms are introduced through ingredients, traffic, dust, or infrastructure issues, they cannot find a niche and become established in the facility by remaining protected from cleaning.

When Water Makes Things Worse

It is tempting to assume that if dry cleaning does not fully address hard-to-clean niches, then performing wet sanitation will enhance efficacy. The opposite is often true. Water interacts with poor hygienic design in ways that enhance risk, creating conditions that can be far more difficult to control. Despite the appeal of water as a "more thorough" sanitation method, moisture behaves very differently in dry facilities than may be expected.

Once water is introduced, it can:

- Carry soils into areas that were previously untouched

- Wick into seams, cracks, and porous materials

- Enable microbial growth

- Create residues that are harder to remove once dried.

Consider a facility experiencing periodic product buildup under a conveyor frame. Routine dry cleaning removes most of the powder, but a thin layer remains on a tight angle. The team opts for a rinse to wash it out. The outcome? Water carries loosened material deeper beneath the frame, damp powder becomes a paste that dries into a cement-like film, and moisture wicks into nearby seams. If Salmonella is introduced into the environment, this niche is now an ideal substrate to support pathogen growth.

Dry cleaning remains the preferred method for many low-moisture environments. When soils are powders, fragments, or dry particulate, dry cleaning tools—scrapers, vacuum systems, brushes, product flushes, and air-assisted tools—remove the bulk of soils and, in some instances, reduce microbial loads by a moderate degree.4,5,6 More importantly, dry methods preserve the biggest safety advantages in these facilities: an environment that does not support pathogen growth.

Preventing pathogen growth is essential because a few Salmonella cells on a surface pose far less risk than the high counts that can develop following a moisture-introduction event. In a dry state, these Salmonella cells remain largely static. Once food soils become hydrated, however, the microenvironment shifts dramatically to support growth. Hydrated residues can support rapid microbial recovery and proliferation, enabling Salmonella to increase by several orders of magnitude within a short period.7 What begins as a low-level contamination event can quickly escalate, increasing the likelihood of product cross-contamination and ultimately, large-scale food safety failures. Preventing growth, therefore, is a critical point of control in low-moisture environments.

Why Sanitizing Alone Does Not Solve Difficult Cleaning Problems

Controlling the conditions that allow for growth is often more impactful than focusing solely on killing the Salmonella cells that may be present. Eliminating every surviving cell is not feasible, and sanitizer efficacy in practice is highly variable, influenced by factors such as shear stress, application time, and operator technique.8 When sanitizer application does not eliminate every cell of Salmonella from each complex niche, preventing Salmonella growth ensures that low-level contamination does not increase. By maintaining conditions that suppress microbial growth, processors avoid a cycle that can drive contamination events. In this sense, environmental control is a more powerful and reliable intervention than a strategy that relies exclusively on hypothetical complete inactivation of microbial cells.

Moreover, sanitizers are designed to reduce microbial loads on clean surfaces. They are not designed to penetrate soils and are, therefore, also limited by poor structural access. When soils remain on or are compacted in niches, sanitizers have reduced contact with the target microorganisms. The same niches that are hard to dry clean will be hard to sanitize. Detail cleaning remains a useful tool for facilities that understand their hygienic design gaps.

Conclusion

Sanitation in low-moisture facilities ultimately depends on understanding how the environment itself shapes risk. Water does not fix hygienic design limitations; it interacts with them in ways that can make problems harder to control. Most dry plants operate with some degree of legacy equipment or unavoidable design complexity. The goal is not perfection when it comes to surface structure; rather, it is awareness—knowing where residues tend to accumulate, how moisture changes their behavior, and which cleaning approaches minimize unintended consequences. By making sanitation decisions that address the constraints of the environment, processors can avoid creating the very conditions that allow risk to escalate.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by a grant from Dairy Management Inc. to Abby Snyder, Ph.D.

References

- Daeschel, D., Y. Singh Rana, L. Chen, S. Cai, R. Dando, and A.B. Snyder. "Visual Inspection of Surface Sanitation: Defining the Conditions that Enhance the Human Threshold for Detection of Food Residues." Food Control 149 (July 2023): 109691. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0956713523000919.

- Chen, Y., V.N. Scott, T.A. Freier, et al. "Control of Salmonella in Low-moisture Foods II: Hygiene Practices to Minimize Salmonella Contamination and Growth." Food Protection Trends 29, no. 7 (July 2009): 435–445. https://www.foodprotection.org/publications/food-protection-trends/archive/2009-07-control-of-salmonella-in-low-moisture-foods-ii-hygiene-practices-to-minimize-salmonella-cont/.

- Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA). "Control of Salmonella in Low-Moisture Foods." February 4, 2009. Available at Regulations.gov. https://downloads.regulations.gov/FDA-2009-D-0060-0002/attachment_4.pdf.

- Chen, L., Y. Singh Rana, D.R. Heldman, and A.B. Snyder. "Environment, Food Residue, and Dry Cleaning Tool All Influence the Removal of Food Powders and Allergenic Residues from Stainless Steel Surfaces." Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 75 (January 2022): 102877. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1466856421002782.

- Daeschel and Chen et al. 2025. "A Simulation Model to Quantify the Efficacy of Dry Cleaning Interventions on a Contaminated Milk Powder Line." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 91, no. 5 (April 2025): e02086-24. https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/aem.02086-24.

- Suehr, Q., S. Keller, and N. Anderson. "Effectiveness of Dry Purging for Removing Salmonella from a Contaminated Lab Scale Auger Conveyor System." International Association for Food Protection Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, Utah. July 8–11, 2018.

- Slaughter, C., S. Chuang, D. Daeschel, L. McLandsborough, and A.B. Snyder. "Moisture Matters: Unintended Consequences of Performing Wet Sanitation in Dry Environments." BioRxiv Preprint. 2026. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.11.26.690674v1.

- Jiao, Y., J. Baker, C. Slaughter, D. Daeschel, and A.B. Snyder. "Reduction of Listeria on Stainless Steel Surfaces is Impacted by Sanitizer Application Method." BioRxiv Preprint. 2026. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.04.09.647964v1.