Chemicals of Concern: The Social and Regulatory Evolution of the Baby Food Category

Changes in regulatory policy and guidance are on the horizon for heavy metals in baby food

The U.S. baby food industry has seen its fair share of advocacy and regulatory headlines in recent years. From the congressional investigation1 into levels of heavy metals in top-selling baby foods, to the infant formula recall,2 shortage,3 and the subsequent Operation Fly Formula,4 the media attention has been in full force—and not necessarily in a good way. When it comes to heavy metals, however, changes in regulatory policy and guidance are on the horizon that will hopefully begin to address some of these challenges.

Those not working in the baby food and infant formula category may be surprised to learn that the issue of heavy metals contamination has been percolating in regulatory and consumer advocacy circles for several years. If the attention by baby food consumer advocates, regulatory calls to action, and subsequent rulemaking are any indication of things to come, there are lessons to be learned by the broader food industry.

Recent History of Heavy Metals in Baby Food Consumer Advocacy

In 2017, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its "Proposed Modeling Approaches for a Health-Based Benchmark for Lead in Drinking Water." EPA developed potential scientific modeling approaches to define the relationship between lead levels in drinking water and blood lead levels, particularly for sensitive life stages such as formula-fed infants and children up to age seven. This report also mentioned the potential of dietary lead exposure in its evaluation.

Later that year, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) released a study5 that examined a decade's worth of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data and found lead in 20 percent of baby food samples. EDF recommended that FDA update its standards, encourage manufacturers to reduce lead levels in food, and take enforcement action when limits are exceeded.

National nonprofit Clean Label Project was next to draw attention to the issue of heavy metals in baby food in 2018. Its initial whitepaper, followed by a peer-reviewed academic publication6 in partnership with the University of Miami, highlighted the extent of the contamination of lead and cadmium, and how U.S. baby foods and infant formula performed relative to California Proposition 65 compliance and the World Health Organization Provisional Tolerable Monthly Intake (PTMI). The study emphasized that products containing rice were higher in both lead and cadmium concentrations and that further research is needed to understand the long-term health effects of this chronic daily low-level heavy metal exposure in babies.

Later that year, Consumer Reports published a report7 that analyzed 50 nationally distributed packaged foods made for babies and toddlers, checking for cadmium, lead, mercury, and inorganic arsenic. The report also included the results of a survey of parents which suggested that parents are often unaware of the potential risks of heavy metals in their children's food. The survey results also suggested that parents believed that children's foods are subject to stricter regulation and safety testing procedures than other packaged foods.

In 2019, Healthy Babies Bright Futures8 conducted a study that revealed that 95 percent of baby foods tested were contaminated with toxic heavy metals. This study reinvigorated the national conversation about the need for urgent FDA action.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →

Congressional Investigation

On November 6, 2019, following reports alleging high levels of toxic heavy metals in baby foods, the Subcommittee on Economic and Consumer Policy requested internal documents and test results from seven of the largest manufacturers of baby food in the U.S., including both makers of organic and conventional products. Following its review, the report's1 recommendations included:

- Mandatory testing—Baby food manufacturers should be required by FDA to test their finished products for toxic heavy metals, not just their ingredients.

- Labeling—Manufacturers should be required by FDA to report levels of toxic heavy metals on food labels.

- Voluntary phase-out of toxic ingredients—Manufacturers should voluntarily find substitutes for ingredients that are high in toxic heavy metals or phase out products that have high amounts of ingredients that frequently test high in toxic heavy metals, such as rice.

- FDA standards—FDA should set maximum levels of toxic heavy metals permitted in baby foods. One level for each metal should apply across all baby foods, and the level should be set to protect babies against the neurological effects of toxic heavy metals.

The investigation garnered significant media attention and consumer response, which prompted action by Congress.

Baby Food Safety Act

The Baby Food Safety Act of 20219 was put forward by Congress and promised to set limits on the amount of lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium contained in baby food by imposing strict requirements on manufacturers to regularly test and verify that their baby foods are under these new, lowered limits for these substances. Under the Act, within a year of coming into effect, manufacturers of baby food and infant formula would be required to adhere to the following maximum levels of heavy metals contamination:

- Inorganic arsenic: 10 parts per billion (ppb), 15 ppb for cereal

- Cadmium: 5 ppb, 10 ppb for cereal

- Lead: 5 ppb, 10 ppb for cereal

- Mercury: 2 ppb.

While perceived to be intended to serve as a short-term fix until FDA could formalize industry policy, now nearly two years later, this Act has not yet passed.

FDA's Closer to Zero

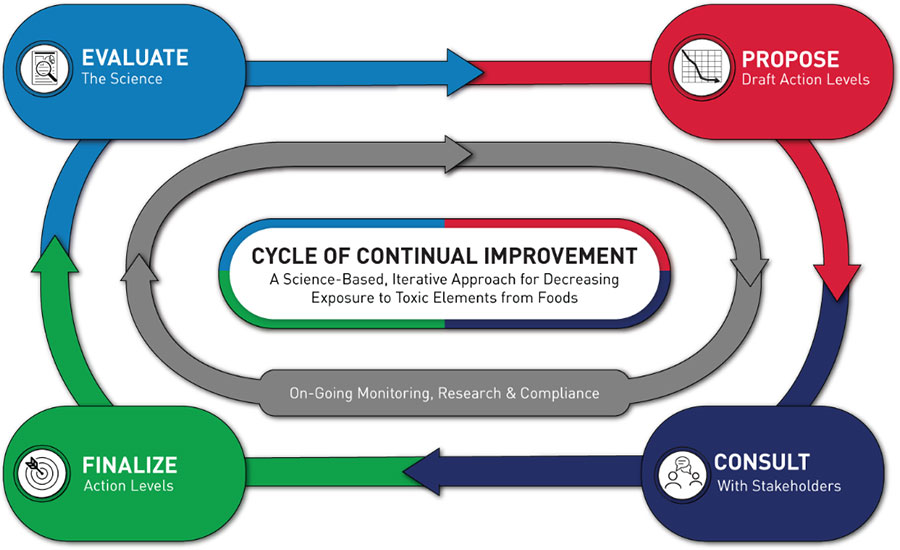

Following the Congressional investigation and the Baby Food Safety Act, FDA released its Closer to Zero10 plan. FDA's goal is to reduce dietary exposure to contaminants to as low as possible, while maintaining access to nutritious foods. While the process (Figure 1) embraces continuous improvement, it has faced its fair share of criticism including the long timeline to implementation and the structural redundancies that prevent more expedient solutions.

Recent accomplishments of the Closer to Zero program include:

- Issuing draft industry guidance for lead in foods intended for babies and young children

- Issuing draft industry guidance for lead in juices

- Continuing to evaluate, together with federal partners, the science for arsenic, cadmium, and mercury, and other work related to establishing interim reference levels.

Also, in June 2023, FDA released final guidance for industry setting the action level for inorganic arsenic in apple juice at 10 ppb, which is consistent with the action level laid out in draft guidance in 2013.

Realities and Tips for Addressing Heavy Metals in the Supply Chain

The EPA's Chemicals of Concern list includes chemical substances found to be harmful or toxic to human health and the environment. This list was published in accordance with a 2016 amendment to the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which requires that EPA evaluate and address the potential risks of chemical substances. While current federal efforts are focused on heavy metals, many other chemicals of concern could face the same level of consumer and regulatory scrutiny (but have not yet), including formaldehyde, asbestos, glyphosate, hazardous air pollutants, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), pesticide chemicals, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

Whether in the baby food/infant formula category or not, when it comes to the issue of heavy metal contamination, there are a few realities that are important for regulators, industry, and consumers to understand:

- Heavy metals are naturally occurring in the earth's crust. They are listed on the periodic table of elements, just as are oxygen and hydrogen, so achieving non-detection for heavy metals with low-level analytical chemistry testing is not always feasible, especially when preserving nutritional density.

- Human causes have exacerbated the problem. Due to issues like mining, hydraulic fracturing, industrial agriculture, and the use of wastewater for irrigation, heavy metals are more concentrated in certain soils.

- The regulatory policies being put forth are focused on the end product with minimal focus on supply chain realities. High-quality and nutritious baby foods come from high-quality, nutritious ingredients. High-quality and nutritious ingredients come from healthy soils and water. Healthy soils and water are the result of strong environmental policies. To date, efforts to address these upstream variables are limited at best. More needs to be done to engage with stakeholders that are key determinants of finished product industry compliance, nutritional density, and success.

- The globalization of the supply chain further complicates matters. Even if we set the most progressive domestic environmental policy, if the same standards and enforcement are not applied within exporting countries, then heavy metal-contaminated ingredients are still destined to enter U.S. shores.

Outlined below are some tips for addressing heavy metals in your supply chain:

- Find the right laboratory partner. When it comes to laboratory testing, there are many options. Look for a laboratory partner that (1) has ISO 17025 accreditation for the specific heavy metal scope for your product type, (2) uses low-level detection—single-digit ppb, and (3) uses inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS). This instrument is capable of detecting metals at very low concentrations.

- Conduct an ingredient risk analysis. Certain ingredients such as rice, some root crops, and hemp-based ingredients are especially good at absorbing heavy metals from soil and water. Conduct a risk assessment of your ingredients and suppliers. Request certificates of analysis (COAs) and "trust but verify" with random testing to confirm results.

- Revisit your Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and Hazard and Risk-Based Preventive Control (HARPC) programs. In the absence of formal federal guidance on heavy metal contamination, HACCP and HARPC programs can be a good default to capture quality assurance and control checks on ingredients and your supply chain.

- Consider the court of public opinion in your quality systems. While the broader food industry may not yet be affected by these emerging regulatory policies, consumers are increasingly aware of the long-term health impacts of heavy metal contaminants. Review your marketing, your claims, and your value proposition, and consider your consumer base.

When it comes to food safety, it does not have to take an act of Congress to voluntarily think about food safety differently. Recognize the changes in regulatory policy and the consumer and societal shifts in food safety and quality expectations, and align your quality systems accordingly.

References

- U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Oversight and Reform: Subcommittee on Economic and Consumer Policy. Staff Report. "Baby Foods are Tainted with Dangerous Levels of Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium, and Mercury." February 4, 2021. https://oversightdemocrats.house.gov/sites/democrats.oversight.house.gov/files/2021-02-04%20ECP%20Baby%20Food%20Staff%20Report.pdf.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "FDA Investigation of Cronobacter Infections: Powdered Infant Formula (February 2022)." August 1, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/fda-investigation-cronobacter-infections-powdered-infant-formula-february-2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Information for Families During the Infant Formula Shortage." July 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/formula-feeding/infant-formula-shortage.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. "11 Operation Fly Formula Flights Completed by September 29." October 6, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/10/06/11-operation-fly-formula-flights-completed-by-september-29.html#:~:text=Under%20Operation%20Fly%20Formula%2C%20the,get%20to%20store%20shelves%20faster.

- Environmental Defense Fund. "EDF Report Finds Lead in 1 in 5 Baby Food Samples." June 15, 2017. https://www.edf.org/media/edf-report-finds-lead-1-5-baby-food-samples.

- Gardener, H., J. Bowen, and S. P. Callan. "Lead and cadmium contamination in a large sample of United States infant formulas and baby foods." Science of the Total Environment 651, no. 1 (February 2019): 822–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.026.

- Hirsch, J. "Heavy Metals in Baby Food: What You Need to Know." Consumer Reports. August 16, 2018. https://www.consumerreports.org/health/food-safety/heavy-metals-in-baby-food-a6772370847/.

- Healthy Babies Bright Futures. "Healthy Baby Food." https://hbbf.org/solutions/healthy-baby-foods.

- 117th Congress. "H.R. 2229—Baby Food Safety Act of 2021." March 29, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2229.

- FDA. "Closer to Zero: Reducing Childhood Exposure to Contaminants from Foods." March 3, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/closer-zero-reducing-childhood-exposure-contaminants-foods.

Jaclyn Bowen, M.P.H., M.Sc., is Executive Director of the Clean Label Project. Before coming to the Clean Label Project, Jackie held numerous technical, standards development, and leadership roles within the World Health Organization Collaborating Centers and NSF International. Most recently, she served as the General Manager of Quality Assurance International, the Director of NSF International’s Consumer Values Verified division, and the Director of NSF Agriculture. Jackie earned a B.S. degree in Environmental Biology from Michigan State University, an M.P.H. degree in Management and Policy from the University of Michigan, an M.S. degree in Quality Engineering from Eastern Michigan University, and a Post-Graduate Certificate in Innovation and Business Strategy from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.